“WHEN THE FIRST Christian pervert, St. Paul, made nature a crime against Christianity, civilization was finished,” writes poet Harold Norse in “Nocturnal Emissions” (1973). “Had he been handsome instead of hideous, the whole course of history might have been happier.” Norse’s opinion is shared by novelist Gore Vidal who, in Live from Golgotha (1992), presents Paul as a sexually maladroit troll obsessed with the handsome, teenaged Timothy. (Timothy, recall, is the recipient of two of Paul’s minor epistles and, in Vidal’s refashioning of Paul’s story, the possessor of “the largest dick in our part of Asia Minor” and of such enormous balls that Paul falls regularly on his knees to worship his acolyte’s “Holy Trinity.”) In Vidal’s vision of early church history, Paul’s highly influential epistolary excoriations against same-sex love prove to be the product of a self-hating homosexual’s determination to deprive others of the pleasure that he himself feels enormous guilt over enjoying.

Fortunately for the evolution of same-sex male love, the viciously homophobic and hypocritically self-righteous posturing that subsequent “defenders of morality” learned from Paul is countered by the biblically authorized tradition celebrating male beauty and homoerotic relationships going back to David, who’s described in the Bible as “ruddy, and withal of a beautiful countenance, and goodly to look to” (1 Sam. 16: 12, King James Version). In the First Book of Samuel, David, a lowly shepherd boy, inspires the impassioned devotion of Jonathan, whose soul is “knit” to that of David and who loves David “as his own soul” (1 Sam. 18: 1). When the animosity of Jonathan’s father, King Saul, forces them to separate, Jonathan and David “kissed one another, and wept one with another, until David exceeded” (1 Sam. 40: 41). And after Jonathan is slain in battle before he and David can reunite, David is left to deliver the most powerful homoerotic funeral elegy that survives from antiquity: “The beauty of Israel is slain upon the high places; how are the mighty fallen! … I am very distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan; very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love was wonderful, passing the love of women” (2 Sam. 1: 19-26).

David’s name derives from the Hebrew word for “beloved,” suggesting his ability to inspire in nearly everyone who sees him—male and female onlookers alike—a passionate devotion that borders on sexual obsession. Michal, Jonathan’s sister, risks the homicidal wrath of her father when she stage-manages David’s escape from the posse sent to arrest him in the dead of night. Later, when, in the exuberance of David’s dance before the Ark of the Covenant, he flashes his sexual goodies to all the world, Michal disdainfully rebukes him for exposing himself to “the handmaids of his servants, as one of the vain fellows shamelessly uncovereth himself” (2 Sam. 6: 20). Michal subsequently finds herself cursed with barrenness for speaking disdainfully of his exhibitionism, as though the biblical redactor would defend the right of the kitchen help to gaze worshipfully upon David’s assets. In some interpretive traditions, King Saul’s tempestuous love-hate relationship with David is explained as the manifestation of a middle-aged man’s inner conflict over desiring his son’s teenaged lover (who, in an early demonstration of biblically inspired “family values,” happens to be the husband of one of his daughters, as well). The Philistine champion Goliath is the only person in the biblical narrative who, upon first looking at David, “disdained him: for he was but a youth, and ruddy, and of a fair countenance” (1 Sam. 17. 42). Goliath must pay with his life for underestimating the Bible’s biggest pretty boy.

No other character in Hebrew biblical narrative inspires such visually charged erotic awareness as David. So it cannot surprise us that David—who’s most often depicted in Western art as the handsome young slayer of the giant Goliath, stripped for battle and muscles tensed from heroic engagement, the head of his defeated adversary oftentimes in his hand or at his feet—evolved historically as the biblically authorized marker of gay male identity. Curiously, the biblical narrator chooses the critical moment in the story—when David comes to the public’s attention by defeating the giant Goliath and liberating the Israelites from the yoke of Philistine oppression—to remind us of David’s extraordinary physical beauty, insisting that the reader look upon him as a potential erotic object rather than as a military champion.

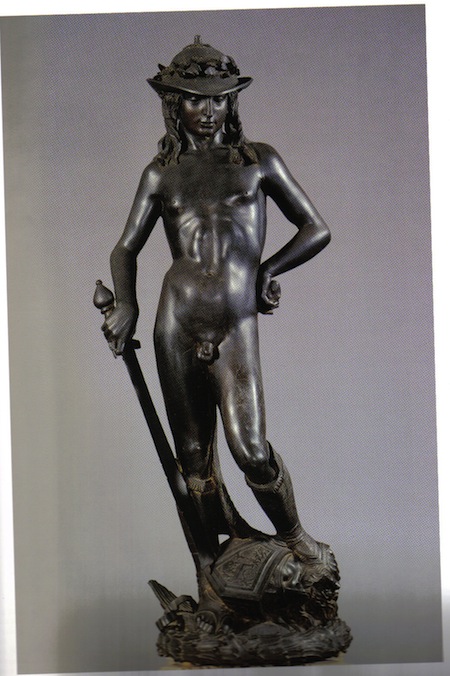

Beginning in the Italian Renaissance, artists took this biblical imperative seriously, daring to depict David as naked or near-naked and inviting others to look upon him as a source of homoerotic delight. Three works deserve particular notice. First, in his bronze David (circa 1450), Donatello created the first sexually charged male nude since the collapse of the classical Greco-Roman æsthetic a thousand years earlier. Second, by imposing his own face upon the head of the decapitated giant in his depiction of David with the head of Goliath (painted before 1610), Caravaggio explored the psychology of an older man’s sexual obsession with a teenage boy. And third, by ignoring the Bible’s emphasis upon the giant-killer as a boy and sculpting instead a larger-than-life adult David (completed in 1504), Michelangelo created the single most visible, culturally authorized icon of male beauty that Europe had known since Hadrian ordered the erection of statues of his drowned (and later deified) lover, Antinous, throughout the Roman Empire.

Through the work of these three artists, David enters the Western world’s cultural lexicon as a synonym for male beauty, in the process allowing gays a socially sanctioned way of thinking about themselves and talking about their desires. More importantly, since becoming canonized as one of the world’s best-known pieces of “high art,” Michelangelo’s David has provided gay men not only with a new way of looking at the self, but of allowing oneself to be looked at in an erotic way, however covertly. Significantly, David as a biblically- or ecclesiastically-authorized representation of naked male beauty is matched in Christian art only by the martyred body of Saint Sebastian, tied to a tree, naked but for a scanty loincloth, and riddled with the arrows of his executioners: the pretty boy as victim rather than, as in the case of David, victor.

Donatello’s Christian Ephebe

In the mid-15th century, when Piero de’Medici installed Donatello’s bronze David in the square fronting his family’s palazzo, those original onlookers could not have anticipated that the sculpture would become one of the most hotly debated artifacts of the Italian Renaissance for late 20th-century viewers. Donatello’s representation of an adolescent, totally nude David, a sword in one hand and the still-helmeted head of Goliath at his feet, was initially exhibited as a symbol of Florentine republicanism, with David the giant-killer serving as a symbol of the fiercely independent city-state’s resistance to monarchy. As such, Donatello’s bronze David was to be considered in the same vein as his Judith, a depiction of the matronly beheader of Holofernes, with which his David was at one time paired. Mounted on a tall pedestal, Donatello’s David rose above the heads of onlookers, commanding the attention of all who passed through one of the busiest squares in Florence.

But Donatello’s David possesses a disturbingly erotic element that suggests a second possible intention on the sculptor’s part. In keeping with the biblical narrative’s description of David as an unprepossessing youth physically outmatched by the Philistine giant, Donatello offers a David who seems not long past puberty: a boy whose musculature is still developing, whose skin seems as satiny soft as a pubescent girl’s, and whose long hair and cocked hip suggest a coquettish allure. More troubling for conservative viewers is the scene of the Triumph of Cupid that decorates the helmet atop the severed head of Goliath, which in Renaissance iconography communicates that the person in question has been overpowered by an unreciprocated desire. Such a reading of David’s conquest of Goliath as being due to his sexual charisma rather than to his military resourcefulness (or, as the Bible would have it, to his “faith in the living God”) is further supported by the suggestive manner in which the feather attached to Goliath’s helmet snakes up the inside of the triumphant boy’s left thigh towards his anus, as though even death cannot quell Goliath’s desire to bugger the beguiling boy.

The brazen sensuality of the bronze David becomes even more apparent when it’s compared to an earlier David that Donatello carved in marble around 1409 for the Duomo. Here the shepherd boy is modestly attired in a full-length cloak and belted tunic, his gaze directed at the viewer rather than downwards and aside, as in the later sculpture, in which the boy’s preoccupation permits the viewer’s gaze to linger unchecked. The bronze David is the first unabashed male nude fashioned in the Western world since the collapse of the Greco-Roman ideal, an ephebe in the classical tradition but not a pagan figure by virtue of his biblical origins. Donatello thus became the first artist to recognize David’s value as a church-sanctioned homoerotic icon.

After Donatello offered for public viewing a totally nude and provocatively coquettish David, the biblical shepherd boy became the quintessential object of male desire. Indeed, as Adrian Randolph has recently suggested in Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence (2002), the bronze sculpture is perfectly in keeping with quattrocento Florence’s reputation among rival Italian city states as a bastion of sodomy. The pedestal upon which the sculpture originally stood in the center of an open square held it just above the heads of onlookers, inviting passers-by to study the David from the rear view as well as from the front, thus making all the more noticeable the snake-like movement of Goliath’s helmet’s plume towards the ephebe’s buttocks. Rarely had homosexual desire been put so publicly on display.

Following Laurie Schneider’s 1973 reading of these homoerotic elements in “Donatello’s Bronze David” (The Art Bulletin, v. 55, June 1973), art historians have divided over the ability of the sculpture to “speak” of homosexual desire. Gay viewers, however, see something in the sculpture that straight viewers perhaps cannot. In a 1976 poem titled “The Giant on Giant-Killing: Homage to the Bronze David of Donatello,” Richard Howard gives voice to the defeated giant who explains that when he went out to confront David, all the world seemed to coalesce in the flesh of the beautiful boy: “No need for a stone! My eyes/ were my only enemy, my only weapon too,/ and fell upon David like a sword.” Howard’s Goliath learns the hard way that simply looking upon a beautiful boy’s naked flesh can be one’s undoing.

Caravaggio: Losing One’s Head

Howard is not the only gay writer to grasp the disruptive, even destructive, power that a beautiful boy holds over his smitten admirer. Adrian Randolph translates from the Arabic an 11th-century poem by Yishaq ben Mar-Saul celebrating the love of a beautiful boy: “Like Joseph in his form,/ Like Adoniah his hair./ Lovely of eyes like David/ He has slain me like Uriah.” Of the three biblical figures celebrated for their physical appearance, David is singled out for his lovely eyes—that is, for the effect that his gaze has upon the speaker.

In the Bible, Goliath’s initial reaction, when he understands that the champion sent by the Israelites to fight him is a comely boy, is one of scorn, which gives way to a drama of looking at, and being looked at by, an attractive naked male. The biblical text thus opens a space for an artist to analyze the psychology of a middle-aged man who is overcome—as in the case of Richard Howard’s Goliath—not by a stone propelled by the shepherd boy’s famous slingshot, but by the cruelly unresponsive glance of a much-desired partner.

Caravaggio is the first painter to concentrate the viewer’s attention upon Goliath, who literally loses his head over a sexually dangerous youth, rather than upon David. In his David with the Head of Goliath, painted some time between 1607 and 1610 and now hanging in Rome’s Galleria Borghese, David is a rough, unmannered street boy, not a sensuous, idealized ephebe. All the lines in the painting lead to Goliath’s severed head, which dangles from David’s outstretched arm in the lower-right corner of the painting. Heavily bearded with mouth still open in astonishment that he should be undone by such an adversary, Goliath’s head emerges from the dark background into the same unseen source of light that plays upon David’s half-naked torso and face. The open fly of David’s loosely drawn breeches and the angle of the sword that the boy still holds in his unseen left hand, however, hint that Goliath’s mouth may be open to receive the boy’s phallus. The suggestion of David’s phallus by a sword gleaming in the darkness is an intimation of sexual violence just enacted or possibly still to come.

For art historians and amateur psychologists alike, the most riveting aspect of Caravaggio’s painting is that the artist’s lover-apprentice Cecco Boneri posed for David, while the head of Goliath is Caravaggio’s self-portrait, transforming the painting into an essay on sexual self-destruction. The sadness of an aging lover attracted to a younger male who’s indifferent to the pain that he causes—a motif that plays through the poems of ancient Greece, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, and the works of Tennessee Williams and William Inge—has never been more poignantly expressed in visual terms than by Caravaggio. The immediate influence of Caravaggio’s motif is revealed by two other versions of the drama attributed to him—the one in Madrid’s Prado, the other in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum—which likewise appear to use Caravaggio’s head as the model for Goliath’s. One of Caravaggio’s rivals—the apparently homosexually inclined but sexually abstinent Guido Reni—similarly imposed Caravaggio’s head upon the decapitated Goliath, making his own David Contemplating the Head of Goliath (Louvre) a censorious comment upon what contemporaries perceived to be the sexual irregularities of Caravaggio’s life.

Caravaggio’s David with the Head of Goliath continues to offer post-Stonewall artists a visual vocabulary for examining their own state of “middle aged crazy.” In a complex meta-artistic moment in the film Caravaggio (1986), for example, director Derek Jarman, imagining Caravaggio’s creation of the original painting, employs a model of his own head for the head of Goliath that’s being held by the boy modeling as David. What’s more, Jarman notes that he associated Caravaggio with fellow filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, who was killed by one of the raggazzi da vita whom Pasolini would pick up for sex and whom he used in such homoerotically provocative films as The Decameron (1971) and Salo (1975).

Conversely, Caravaggio’s image of David with the head of his defeated adversary gave the late Paul Cadmus the opportunity playfully to explore his long-term relationship with his lover, Jon Andersson, in Study for a David and Goliath (1971). Cadmus’ painting offers a domestic scene in which the artist sits on the floor drawing, his back supported by the bed on which his naked lover partly reclines. A reverse-image copy of Caravaggio’s David with the Head of Goliath hangs on the wall above the bed, and a book opened to Caravaggio’s Love Conquers All sits amid the clutter at the artist’s work station. The T-square that Andersson is holding to help the artist becomes a sword, while the red scarf around Cadmus’ neck suggests the bloody severing of the artist’s (Goliath’s) head from his body. Andersson, a professional dancer whose perfectly muscled body was drawn repeatedly by Cadmus in the course of their long partnership, grins zanily, even malevolently, at the viewer, possibly suggesting—in the words of Cadmus biographer David Leddick—“how beauty can undo the importance of art in an artist’s life.”

It is worth noting that, although Harlem Renaissance artist Richard Bruce Nugent never communicated in his work with Caravaggio, he dared to reconfigure the relationship between Goliath and David in 1947 by drawing a giant whose oversized hand seems protectively and affectionately to rest on the delicate shoulder of a svelte youth, who is clad only in a form-fitting tunic and a pair of high-top sneakers. Goliath’s trousers are unbelted and open to the line of his pubic hair, and a phallic-shaped fern juts suggestively up from the ground towards his unseen buttocks. In his right hand, Goliath balances a grotesquely thick and gnarled cudgel, the head of which is angled in the direction of an opening in the wall behind them—a pair of symbols that hint at phallic penetration. The face of the giant is as grotesquely deformed as that of David is delicately attractive. The image is as much a comment on Nugent’s feeling of being rendered freakish by his sexual desires, as it is an act of courage to depict the giant standing side-by-side with the object of his desire, looking the viewer directly in the eye. This is the only painting I know of that depicts David and Goliath as emotional equals despite their disproportionate sizes, and in which the two figures face the viewer, as though standing in solidarity against a censorious world. Paradoxically, while his drawing is as great a departure from the details of the biblical narrative as it seems possible for an artist to make, it is a natural step in the evolution of gay identification with David.

Michelangelo’s “Less Delicate Creation”

The power of an image to supplant the biblical text that it was initially intended to illustrate becomes even more clear in the case of Michelangelo’s David. At fourteen feet tall (not counting the great pedestal on which it stands), Michelangelo’s David is no longer the boyish underdog who depends entirely upon his faith in the living God, but has become the giant himself. In Michelangelo’s imagination, David is not a winsome boy open to sexual penetration by adult members of the community but instead a fully mature, self-possessed adult male beauty. The summation of human perfection executed in unblemished white marble, Michelangelo’s David is a figure to be worshiped, not penetrated or transgressed. David’s casually confident stance and furrowed brow betoken a removal from the viewer’s world. Perhaps because this David seems so perfectly self-contained, it has become one of the central icons of Western art.

Michelangelo’s David gives witness to the artist’s Neo-Platonic philosophy, which holds that the beauty of the soul can only be communicated through the beauty of the body. But the celebration of physical beauty in the pursuit of a spiritual ideal can easily become a pretext for indulging the very desires that Neo-Platonism urges men to transcend. It is this tension between the spiritual ideal and the erotically charged physical perfection by which it is reached that has made Michelangelo’s David among the most famous works of art in the modern world. And it’s a work that has been routinely adopted by gay men as a symbol of their desire. Because it is recognized as “high art,” any person of taste is justified in displaying it. As such, it’s also a sign that closeted or guarded gay men can use to communicate to like-minded persons without arousing the suspicions of the censorious. Pop culture historian Michael Bronski has commented upon the reproductions of the David that were displayed in many gay men’s homes in the 1950’s: “The Davids were not just erotically pleasing pieces of inexpensive art; they were also signals to visitors in the know that the homeowners were homosexual, functioning as a kind of aesthetic Morse code of sexual identity.” Such a code could operate even more effectively when publicly signaling an invitation to engage in male sexual play. In Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library (1988), for example, the protagonist enters a theater whose front window had been “painted white with a stencil of Michelangelo’s David stuck in the middle,” effectively preventing the unsympathetic from looking in but allowing the cognoscenti to know what kind of atmosphere they would find within.

The statue’s ability to signify two very different meanings simultaneously is captured by poet Harold Norse in his “Meditations of the Guard at the Belle Arti Academy” (circa 1958), in which a bored and underpaid museum guard expresses his resentment of both the heterosexual tourists, “head in the clouds, seasick with awe, [who]whisper …/ Great, great!”, and the “queers who grab a feel of the stone,/ of David’s legs and feet.” Michelangelo’s David allows heterosexual viewers to feel culturally superior in their admiration of artistic greatness while granting gay viewers an opportunity for a kind of sexual expression in public.

Writing of his first visit to post-World War II Italy, Tennessee Williams assessed the local “talent” for a friend still home in the U.S. “I have not been to bed with [Michelangelo’s] David but with any number of his more delicate creations.” Ironically, in the post-Stonewall period, when the communication of gay desires no longer needs to be camouflaged as “high culture,” the David has been reduced to camp. The image is now so visible, and its potential gay meaning so widely acknowledged, that the sculpture has been taken down from its pedestal, as it were, and presented in an explicitly erotic way. Thus in the mid-1970’s a hard-core porn film titled Michael, Angelo, and David—starring Marc “Ten and a Half Inches” Stevens—could play at a seedy gay cinema in midtown Manhattan called The David (which had white silhouette on blackened window and a poster in the door advertising an “All Male Cast”). When director Franco Zeffirelli commissioned a contemporary recension of Michelangelo’s David from Tom of Finland, the artist produced, in the assessment of biographer F. Valentine Hooven, a figure with a broader chest, more prominent nipples, and a genital endowment “at least quadruple the size of the one Michelangelo gave him. And … instead of wearing a frown of determination, Tom’s David slyly peeks at the viewer as if to say, ‘I know what you’re looking at!’”

In 1977, when Gay Sunshine Press published Harold Norse’s Carnivorous Saint, the poem “Meditations of the Guard at the Belle Arti Academy” was illustrated by a photographic collage in which an enormous marble phallus was inserted between the buttocks of Michelangelo’s David, as if to remove any pretense of the sculpture as high art, insisting upon its homoerotic essence. In recent years, the David has become the subject of a set of refrigerator magnets that allow him to be dressed in such iconic gay guises as a California surfer boy, a leather-clad biker, or a jock. There’s also a barbecue apron that allows the cook’s head to appear on David’s body and a switch plate in which the switch becomes David’s disproportionately large phallus, whether in the up or down position.

In its October 2004 list of “100 People, Places, Things and Events That Shaped the History of Sex,” Unzipped magazine ranked Michelangelo’s David as 41st in importance, placing it behind Madonna, steroids, bathhouses, and the city of Amsterdam, but still ahead of Fire Island, Marky Mark’s Calvin Klein Underwear Campaign, and The Village People. The magazine’s citation read: “Michelangelo created David, that famous 14-foot-high statue with the small penis and rock-hard ass. Did you know that in the 16th-century a small penis was considered the most perfect type? They decided that it was more æsthetically pleasing that way, and that big cocks were vulgar. People sure were dumb back then.” Here, the David is seen as a naive ideal that the supposedly more liberated post-Stonewall gay world is free to criticize. In a society in which the perfect body is available to any male willing to spend hours a day at the gym, gay physical self-image need no longer be authorized by a biblical figure rendered as “high art.”

Jean-Raymond Frontain, author of Reclaiming the Sacred: The Bible in Gay and Lesbian Culture (second ed., 2003), is working on a study of Terrence McNally’s plays.