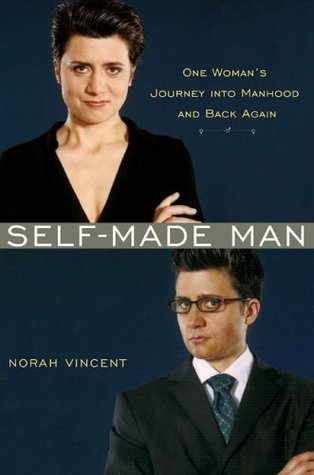

Self-Made Man: One Woman’s Journey

Self-Made Man: One Woman’s Journey

Into Manhood and Back Again

by Norah Vincent

Viking. 290 pages, $24.95

FROM SHAKESPEARE to Mrs. Doubtfire, gender deception as a plot device usually has a predictable trajectory. The elaborate subterfuge, no matter how it’s initially conceived, ends up revealing more to the deceiver than s/he ever anticipated. After much hand-wringing, not to mention comedy, the costume comes off, the truth comes out, hearts are (perhaps) broken and mended, and valuable lessons are learned. Much of the same can be said for Norah Vincent’s unique book, Self-Made Man, which is a journalistic account of actual events rather than a work of fiction. Not since John Howard Griffin used injections to darken his skin and traveled in black America for his controversial 1961 book Black Like Me has a person taken such drastic steps to experience firsthand what it’s like to be someone from a different walk of life.

The difference between Vincent and Griffin’s project, of course, is not only that gender is a category that cuts across all other identities, but that the divide between male and female is much more profound than the one between black and white. The comparison between Griffin and Vincent prompts the question of how race and ethnicity influence gender, and it would be fascinating, to say the least, to see how Vincent’s exp eriment might have been influenced by racial factors (how do the experiences of Asian, Black, Latino, and Caucasian males stack up against each other, for example?) But Vincent has her hands more than full in making the transformation from white, educated lesbian to white, less educated, heterosexual male.

eriment might have been influenced by racial factors (how do the experiences of Asian, Black, Latino, and Caucasian males stack up against each other, for example?) But Vincent has her hands more than full in making the transformation from white, educated lesbian to white, less educated, heterosexual male.

Vincent, an out lesbian, got the idea for this project after a “drag king” escapade in New York City’s East Village in 1999. Attired as a kind of “frat boy” in a cap, loose jeans, and a flannel shirt, she realized why straight men were so careful in the way they look at other men. “For them,” she writes, “to look away was to decline a challenge, to adhere to a code of behavior that kept the peace among human males in certain spheres just as surely as it kept the peace and the pecking order among male animals.” This brief foray into male identity eventually inspired a more concerted effort to explore American manhood.

a flannel shirt, she realized why straight men were so careful in the way they look at other men. “For them,” she writes, “to look away was to decline a challenge, to adhere to a code of behavior that kept the peace among human males in certain spheres just as surely as it kept the peace and the pecking order among male animals.” This brief foray into male identity eventually inspired a more concerted effort to explore American manhood.

Vincent answers the obvious questions right off the bat. She examines her own sexuality and gender identity and offers her coming out tale succinctly but movingly. She also explains the details of her masquerade—how, for example, she managed the illusion of convincing beard stubble, how she concealed her breasts, lowered her voice, and so on. These intriguing details lend the quality of an adventure tale to her book. After successfully passing as a man in public, Vincent soon realizes that she’ll get more meaningful results by interacting with other men in environments that are either predominantly or exclusively male.

In separate chapters that explore such general aspects of life as friendship, sex, love, and work, Vincent details how she joined a male bowling league, frequented strip clubs, dated women, worked as a salesman, infiltrated a men’s encounter group, and even joined a monastery. Each separate journey makes for fascinating reading, and Vincent proves herself an engaging, erudite, and down-to-earth tour guide. She is also admirably honest about how her project exposes her own prejudices and preconceptions. During her interactions with the largely blue-collar, uneducated members of the bowling league, for example, she admits that she’s surprised by the sensitivity and acceptance that the men immediately bestow upon Ned, Vincent’s male alter ego. Her chapter on dating women (most of whom she meets on-line) should be required reading for all single men and women.

During each segment of her life as Ned, Vincent is faced with the question of whether or not to reveal herself to Ned’s largely unsuspecting friends and romantic partners. In some cases she decides not to do so. When she does, she invariably meets with disbelief, a fact that she attributes not so much to the quality of her disguise as to the general tendency of people to see what they want to see. But the reactions are not always predictable, as is the case with some of the women who date Ned and later meet Norah.

Vincent’s life as a man presents not only physical and logistical challenges, but psychological trials as well. She comes dangerously close to a nervous breakdown. Though she admits that the crisis has none of the high drama one associates with “cracking up,” it is nonetheless a serious and unintended consequence of her quest. “When I plucked out, one by one, my set of gendered characteristics, and slotted in Ned’s, unknowingly I drove the slim end of a wedge into my sense of self, and as I lived as Ned … a fault line opened up in my mind, precipitating small and then increasingly larger seismic events in my subconscious until the stratum finally gave.” Fortunately, Vincent emerges intact, and lives to tell her tale. She achieves some astonishing revelations during her life as a Ned, and she conveys these with a wise, humorous, and humane eloquence.

Jim Nawrocki, a writer based in San Francisco, is a frequent contributor to this journal.