Robert Duncan in San Francisco

Robert Duncan in San Francisco

by Michael Rumaker

City Lights. 158 pages, $12.95

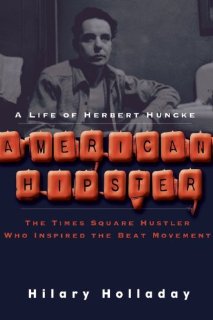

American Hipster: A Life of Herbert Huncke

American Hipster: A Life of Herbert Huncke

by Hilary Holladay

Magnus Books. 378 pages, $17.95

BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE was a small, short-lived (1933-1957) liberal arts school in rural North Carolina that had a big, long-lasting impact on American arts and letters. Its faculty included the likes of John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Alfred Kazin, and Buckminster Fuller, who conceived of his famous geodesic dome while there. Albert Einstein and William Carlos Williams were among Black Mountain’s lecturers. Its list of alumni is equally impressive, with names like Robert Creeley, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Arthur Penn, Ruth Asawa, and Robert De Niro Sr. (the actor’s father).

Black Mountain’s founders were inspired by the American Progressive movement of the early 20th century, in particular by such reform-minded thinkers as John Dewey, who argued in Schools of To-Morrow (1915) and Democracy and Education (1916) for education focused on interaction, experience, and community, rather than more traditional methods like memorization.

And the school gave America a unique literary legacy, namely the Black Mountain Poets, who included Charles Olson, Robert  Creeley, Robert Duncan, and Ed Dorn, among others. Led mainly by Olson, they championed an “open” and line-based form of composition, as opposed to the then still-fashionable formalism of poets such as Yvor Winters and John Crowe Ransom. The Black Mountain style is often described as avant-garde, and it had a direct line, through Creeley, to postwar Beat generation writers such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac.

Creeley, Robert Duncan, and Ed Dorn, among others. Led mainly by Olson, they championed an “open” and line-based form of composition, as opposed to the then still-fashionable formalism of poets such as Yvor Winters and John Crowe Ransom. The Black Mountain style is often described as avant-garde, and it had a direct line, through Creeley, to postwar Beat generation writers such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac.

The impact of the Black Mountain Poets and Beat writers was social as well as literary. Their embrace of free-form composition can be read as a corollary to their broader rejection of postwar American conformity and consumerism. And with Robert Duncan—who made waves in 1944 after he published a controversial essay “The Homosexual in Society”—and Ginsberg among them, they were some of the first American writers to identify publicly as gay or at least as sympathetic to gay rights.

This is the context for Michael Rumaker’s memoir, Robert Duncan in San Francisco, which includes only a brief background on Black Mountain and its influence. This sketchiness is justified by the fact that Rumaker covered his North Carolina experiences separately in another memoir, Black Mountain Days (2003). In Robert Duncan in San Francisco, the reader finds himself in the middle of an extended conversation. It is not a linear narrative. At times, it even reads like prose poetry. And its title is misleading, for the book (an expanded re-issue of the 1977 edition) is as much about Rumaker in San Francisco as it is about Duncan. Some critics faulted the book for this when it was first published, but the criticism seems unfair. The relationships and associations among the Black Mountain group were so vital, and nourished such a wide array of innovative art and writing, that no telling of the story could focus on any one individual.

Rumaker, born in 1932, came from humble beginnings, as did Robert Duncan. Olson and Creeley were among his teachers at Black Mountain, as was Duncan, who served as Rumaker’s examiner and approved him for graduation in 1955. Two years later, Black Mountain had to close because of financial difficulties, but its students and faculty maintained their connections. Rumaker moved to San Francisco, where Duncan, Creeley, and the Beats were making literary history. His book includes his memories of life at Black Mountain and his reunion with Duncan in Philadelphia soon after he graduated, before it focuses on the Creeley-Beat-Duncan-San Francisco milieu.

Rumaker’s descriptions of life as a gay man in 1950s San Francisco, including reports of police persecution of gays, are a good antidote to the more sugar-coated accounts of the era’s Beat and jazz scenes. It can make for chilling reading. One night, Rumaker was one of many men arrested on Polk Street, then a noted gay cruising area, simply for being gay, or appearing to be so. The judge presiding over Rumaker’s courtroom appearance was Clayton W. Horn, the same judge who ruled in favor of City Lights publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti at the conclusion of the obscenity trial for Ginsberg’s Howl.

Within this chaotic and often frightening atmosphere, Robert Duncan lived a kind of separate peace, ensconced in a comfortable, book- and art-filled home with his life partner, the painter Jess Collins. Duncan’s home served as an alternative, at least for Rumaker, to the often rootless and restless life of a gay man. It was a lifestyle that Rumaker admired and aspired to. He writes of Duncan lovingly, expressing his gratitude for the poet’s mentorship and friendship. But he writes with honesty too, casting a perceptive and sensitive eye on Duncan’s vulnerabilities. In a recent interview, included in this edition, Rumaker suggests that Duncan’s silence about the first edition of the book was probably because Duncan chafed at Rumaker’s frank portrait of him.

One should not turn to Robert Duncan in San Francisco expecting a full account of Duncan, or even of Rumaker, at the time and place referenced in the book’s title. While Rumaker does pack a lot into this slim volume, it’s not an exhaustive examination of its subject. It is, however, a portrait of friendship among a group of exceptional writers, and a historical document about gay life at a unique time and place in America. Rumaker’s memoir is a valuable addition to the books by and about Black Mountain writers, and one hopes that it engenders further interest in, and study of, their work.

HIS NAME is not widely known, but Herbert Huncke (1915–1996) might conceivably be called the father of the Beat movement. Although he published three books of mostly autobiographical writing in his lifetime (a fourth was published posthumously), he did not necessarily identify as a writer. He did not, in fact, identify as much of anything. He was a lifelong junky who was never gainfully employed for long and who engaged in petty theft and hustling to finance his habits. He was rootless; he lived in New York City most of his life (in near poverty, moving often), had a brief residence in San Francisco, and did at least a decade of prison time. His sexual relationships were mostly with men, but he shunned labels like “gay” and “queer” and had some romantic attachments to women.

Huncke was a grand personality and a born storyteller, and these qualities, along with his outlaw lifestyle, made him attractive to a group of Columbia University students in the 1940s who, inspired by his life, went on to produce the seminal works of Beat literature. There are characters based on Huncke in John Clellon Holmes’s Go (1952, the first Beat novel), William Burroughs’s Junky (1953), and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957). Huncke is also the “angel-headed” hipster in Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl.”

Huncke (pronounced “hunky”) had few loyalties or scruples. He was not above stealing from his writer friends, and was infamous for pilfering their typewriters to sell for drug money. He was also a kind of heroin Svengali, initiating more than a few young men and women into the habit, usually with predictably tragic consequences. And yet this Times Square hustler seemed to have hypnotic powers over Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, and many others in the Beat tribe. They forgave Huncke his many sins because he fascinated them with his view of a world they could admire but never truly be a part of. Hilary Holladay’s American Hipster, the first full-length biography of Huncke, is a thorough and balanced assessment of his strange life and his undeniable influence on a unique group of American writers.

There are conflicting stories about how the Beat movement got its name, but Holladay gives the credit to Huncke. He was forever telling Kerouac, Ginsberg, and everyone else, “I’m beat, man,” and he said it in a way that conveyed not only the physical exhaustion brought on by hard living, but a deeper, existential weariness. Postwar America was entering an economic boom, but for people like Huncke, prosperity was elusive and conformity was betrayal. Huncke chose his path, and paid the price, but he did it with a peculiar dignity, following his own rules and becoming an outlaw saint for the Beats.

Holladay begins her book with a story about the twelve-year old Huncke, living in Chicago, that proves emblematic of the man he will become. Given streetcar fare by his mother, he’s sent off to visit his father across town. Instead, he runs away, bound for New York City by way of Massachusetts. He doesn’t make it, lands in jail, and has to be retrieved by his father. Huncke always resisted the conventional and was forever on the move, and he learned early on the street-smart skills of a savvy con man, talents that he would call upon for the rest of his surprisingly long life.

Although he was born into economic stability and could have taken over his father’s successful machine parts business if he’d wanted to, he opted instead to strike out on his own. His parents were troublesome in different ways, and he felt little connection to his family. If Huncke’s father was distant and aloof, his mother was disturbingly close to her son, less like a wise mother than like an unstable older sister. He called her “Marguerite” rather than “mother.” She told young Herbert all the gory details of her dysfunctional sex life. He had a more appropriately nurturing relationship with his maternal grandmother, who was also a gifted raconteur and who encouraged Herbert’s creativity and wanderlust.

Huncke left Chicago, and his family, as soon as he could. He wandered the country and even had a stint in the Merchant Marines before moving to New York City. Huncke’s Beat connection began with Burroughs, who knocked on Huncke’s front door one day in 1944, searching for one of Huncke’s roommates. That meeting was the spark that got the Beat movement going. Holladay tells the subsequent story very well, making good use of the wealth of published and unpublished Beat writings available to her. She offers insightful psychoanalytical portraits of the movement’s major figures, as well as many of its marginal ones.

But there was much more to Huncke than his connection to the Beats, and Holladay helps flesh out the story of this shadowy man. She describes, for example, Huncke’s unique and close relationship with the famous sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, a fascinating tale that seems to deserve its own book. With the exception of Ginsberg and Burroughs, Huncke outlived most of the Beat figures by decades. He enjoyed modest fame within Beat circles as a revered elder and teacher. Although Huncke disdained nostalgia and preferred to look forward rather than backward, he was quite happy to have a young audience hungry for tales about his friendships with those in the Beat pantheon. He toured often, even internationally, giving readings and lectures.

Holladay sees Huncke, despite his faults, as a compassionate man who, unlike his famous fellow travelers, was capable of writing deeply and lovingly about the many truly “beat” street people who moved within his circle. Offering excerpts of his poems and prose along with sensitive analysis of his work, she makes her case that, “No matter how hard the others tried, they could never convey the beat essence with Huncke’s authority or his peculiar delicacy.” Her biography of Huncke is a much-needed addition to the growing literature about the Beats as individual artists and as a cultural movement.

Jim Nawrocki, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in San Francisco.