Published in: January-February 2017 issue.

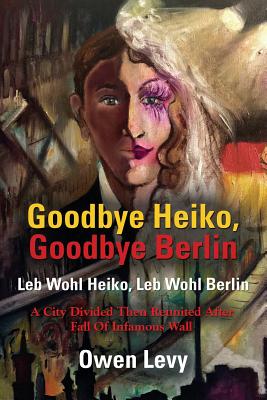

Goodbye Heiko, Goodbye Berlin: A City Divided Then Reunited After Fall of Infamous Wall

Goodbye Heiko, Goodbye Berlin: A City Divided Then Reunited After Fall of Infamous Wall

by Owen Levy

BookLocker.com, Inc. 281 pages, $18.95

WHAT IS IT that one loves about a person or a city? Does loving a person or a place mean that you’ve found something there that corresponds to something deep within your inner core, or that the person or place fills some void in your inner experience?

Such questions are posed by Owen Levy’s novel Goodbye Heiko, Goodbye Berlin.