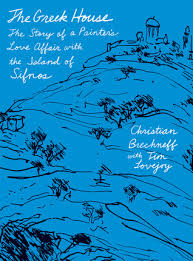

The Greek House: The Story of a Painter’s

The Greek House: The Story of a Painter’s

Love Affair with the Island of Sifnos

by Christian Brechneff with Tim Lovejoy

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 304 pages, $27.

Christian Brechneff was a young, impressionable Russo-Swiss painter when he first set foot on the Greek island of Sifnos in 1972. This reader-friendly memoir describes his complex, changing relationship with the island’s small, conservative, and inward-looking population across three decades. It also covers many other things, such as Brechneff’s gradual coming to terms with his sexuality, his long-term relationship with co-author Lovejoy, his artistic career, and, most instructively, the threats and opportunities brought by the sort of foreign investment and immigration that he exemplifies. While Sifnos begins as an artistic inspiration to Brechneff and a sanctuary from modern life, he comes to witness the ways in which newcomers just like himself, with their need for fast cars, fast food, and the latest computer technology, progressively hold hostage the very qualities that bring them to Greece. The marina is developed beyond all recognition to accommodate wealth-bringing speedboats. New roads are built. Phones proliferate. Tourism thrives—and dominates. Brechneff stays for as long as he can bear, but—struck by the increasing venality of the islanders whose simplicity and generosity he had treasured—he recognizes that it’s time to move on. This is a warts-and-all self-portrait in which Brechneff owns up to the snobbery he developed toward later waves of tourists, arguing that he understood the locals better and had found the island “first.” Illustrated by the author’s beguiling sketches of the then-undeveloped paradise, this book is an attractive addition to FSG’s growing series of gay memoirs exploring non-stereotypical gay lives.

Richard Canning

The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary

The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary

Film and Television

by Maria San Filippo

U. of Indiana Press. 232 pages, $25.

Anyone who hasn’t been living in a remote cabin for the last twenty years knows that gay, lesbian, and even transgendered characters have been increasingly visible in films and on TV. But what about bisexuals? There things get murkier. Yes, we sometimes see bisexual situations in which gay or straight characters venture temporarily to the other side, but it’s harder to recall characters who openly identify as bi. Maria San Filippo examines this state of affairs in her new study. She limits her scope to films and shows produced since the 1960s, because it’s only since then that bisexuality has been publicly and politically recognized as a distinct identity. Despite that recognition, she finds that bisexuality has remained in the background on both the big and small screens, evaded through an ongoing series of “missed moments.” She prefaces her analysis with a helpful overview of the foundational research on human sexuality (Freud, Kinsey, et al.), queer theory, and bisexual theory. Indeed, this is a solidly academic tome, and San Filippo’s prose reflects it. She’s fond of neologisms like “(in)visibility,” “un(der)spoken,” and “bi-textuality,” and her jargon-heavy sentences can sometimes make for tough going. But her study is full of fresh insights about a mostly neglected subject, and she makes good use of a wealth of cultural material. Central to her argument is that bisexual identity challenges the dominant model of sexuality (i.e., “monosexuality”), which is gender-focused: you either like the opposite sex or the same sex. Bisexuality, however, is inherently pluralistic and ambiguous. In mapping on-screen depictions of bisexuality, San Filippo focuses on storytelling in which gender-based monosexuality is challenged by more complex varieties of erotic desire. She chooses examples from international art cinema, sexploitation films, contemporary Hollywood productions (including “bromance” movies), and TV. She invites us to regard our culture’s recent depictions of sexuality with a more expansive and critical eye, and offers a solid critical framework with which to do so.

Jim Nawrocki

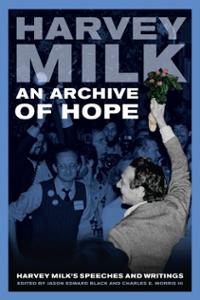

An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk’s

An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk’s

Speeches and Writings

Edited by Jason Edward Black and Charles E. Morris, III

U. of California Press. 256 pages, $34.95

In a 59-page introduction, Morris and Black generously detail the social, economic, and political climate that catapulted Harvey Milk into the national spotlight as the first openly gay elected official in San Francisco in 1977. Frank M. Robinson, Milk’s speech writer, calls Milk an “oracle” who “spoke not only for today but also for tomorrow.” The 45 writings here include interviews, speeches, letters, press releases, campaign literature, columns for the gay press, editorials, transcriptions of audio recordings and TV broadcasts, and draft documents. Milk wrote a column for San Francisco’s Bay Area Reporter, and ten of the writings are from that newsweekly. For each document, the authors give helpful political and historical perspectives on the era. Milk’s politics were motivated by his passionate belief in gay equality. In a campaign document of February 1975, he announced a second run for city supervisor. Describing himself as a “populist,” he hoped that young gays would “derive encouragement and strength from our battle for equality and acceptance.” In June 1977, Milk delivered what’s known as the “Hope Speech,” an oratorical tour de force. During his ten-month service as Supervisor, he tackled important state and local issues of his day, including decriminalizing homosexuality, improving city services for gays, and opposing political efforts, like the infamous Briggs initiative, to discriminate against gay people. Milk also took on national issues like Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusade in Florida, and he called on President Carter to extend his human rights work to include gay people. Morris and Black, both academic communications scholars, have made an important contribution to the corpus of work on Harvey Milk as a writer and an orator.

James Patterson

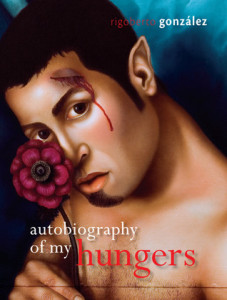

Autobiography of My Hungers

Autobiography of My Hungers

by Rigoberto González

U. of Wisconsin Press. 128 pages, $19.95

Now a college professor, Rigoberto González was raised in poverty and dysfunction in Mexico and California. His earlier memoir, Butterfly Boy: Memories of a Chicano Mariposa (2006), is a luminescent work of humor and tragedy, anchored in a three-day bus trip that he took with his father in the early 1990’s when he was a college student. In that memoir, he reflected on his mother’s death from heart disease when he and his younger brother were children; his father’s difficulty caring for his family, both financially and emotionally; his extended family’s struggles with illiteracy, poverty, and farm worker conditions in California. The little boy who was always at the top of his class—and openly effeminate from an early age—managed to escape to college and involve himself in a variety of love affairs. Here González revisits many of the same events that took place in Butterfly Boy but in a more impressionistic manner. Vignettes in the new book are separated by fifteen brief poems, all of which are titled “Piedrita,” or little stone. Piedritas, González reminds us, are often mixed in with dried beans and need to be removed before the beans are cooked. Although González’ family were not practicing Catholics, it’s worth noting that the word is also associated with the beads of a rosary. One piedrita reads in its entirety: “I lost my appetite/ after my father died/ All these years later,/ nothing tastes the same.” Vignettes concern the death of his mother, actions of his callous father (a drinker, a cruel man who could still be fun), and finally his escape to college. González suffered from food-related disorders for years: as a child, prolonged malnutrition and hunger; later, obesity, bingeing, and severe dieting. He writes: “I was afraid of my hungry gay body. I was afraid of the light in the mornings, and the birds chirping.”

Martha E. Stone