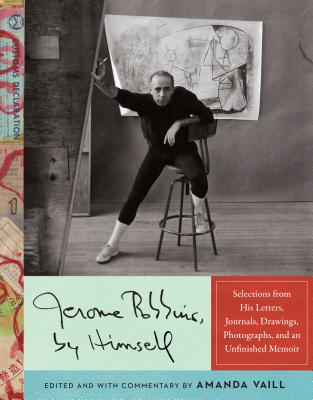

Jerome Robbins by Himself: Selections From His Letters, Journals, Drawings, Photographs and an Unfinished Memoir

Jerome Robbins by Himself: Selections From His Letters, Journals, Drawings, Photographs and an Unfinished Memoir

Edited by Amanda Vaill

Knopf. 399 pages, $40.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION did major damage to American society, but for at least one individual, it proved exactly the kickstart he needed for his genius to flower. Born in 1918, Gershon Wilson Rabinowitz had intended to study “politics or economics maybe” in college. Instead, when he graduated from high school, he discovered he had to go to work. He found all kinds of jobs and eventually found work dancing, something he’d enjoyed doing at school. Soon he ended up in a small dance company called the American Ballet Theatre.

Those three words sum up what he quickly became when he moved to Manhattan as an American ballet dancer and a choreographer named Jerome Robbins. As a dancer, he shouldn’t have been exceptional: he was below medium height and thin, but he was flexible, with reserves of energy, and unafraid of hard work. Above all, he had ideas—lots of them. By the age of 26, he had met many other eager young American neighbors in the West Village: dancers, composers, writers, and theater people. World War II was raging, and he proposed a short ballet about three sailors on leave in New York. His neighbor, Leonard Bernstein, liked the idea and composed a dance score that Robbins choreographed. Their hip, contemporary, almost casually stylish Fancy Free was an instant hit. It brought both young men fame, as well as the ability to turn it into a full-fledged Broadway musical. On the Town opened the following December and was also a hit. Robbins’ vibrant new style of dance-making led to offers to choreograph more musicals, including Look Ma, I’m Dancing and High Button Shoes. Eventually he would direct and choreograph twenty Broadway shows.

Robbins moved on to dance for the newly formed New York City Ballet, which, under George Balanchine, would soon outstrip the French and Russian schools to become the ballet company of the century. His idea for a contemporary Romeo and Juliet, with Bernstein composing again, opened in 1955 as West Side Story. With its athletic, violent, sociologically complex, openly ethnic and sexual elements, the musical mesmerized Broadway and the dance world. Soon Hollywood would call, and Robbins would tentatively work there too, creating nearly authentic Asian dances for The King and I, all the while continuing to tend to his multiple home fires. The amazing pyrotechnics of Russ Tamblyn and his six male cohorts in the film Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, or of the waiters in Streisand’s Hello Dolly—high points in filmed dance—became possible only after Robbins had liberated the male body on stage and screen and wildly expanded its reach and its depth.

Following the arc of his life and career through his letters and journals, one can readily discern how this child of immigrants felt, acted, and thought. For example, the letters of the early 1940s sound like the dialogue of light movies of the same era. Of course, his language changes once Robbins and his colleagues grow into their creative mastery and become internationally famous. His correspondence with Arthur Gold and Tanaquil Le Clercq, two lovers turned lifelong friends, is always heartfelt and sincere, even when he’s clearly treading gingerly on their feelings.

By then, however we are reading another, more solid kind of Robbins: catalyst for an American dance revolution in which specifically masculine movements have appeared, evolved, and taken over. We read along as he warns Bernstein to give him credit when and where it is due. We read as he negotiates with Lincoln Kirstein over the latter’s ludicrously low New York City Ballet salary offers.

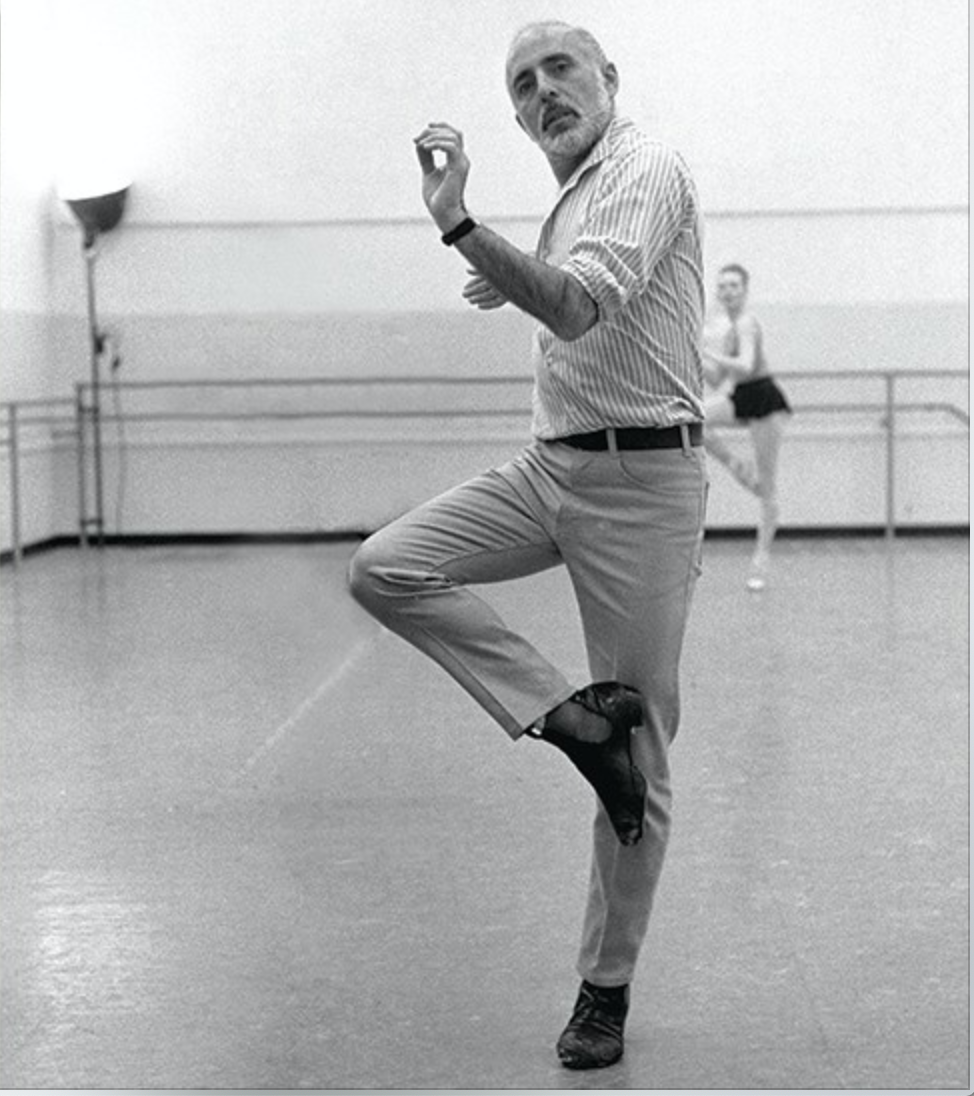

The book is compelling reading, even when it begins to turn dark, later in Robbins’ life. One would expect someone who danced solos into his middle years to have limiting physical ailments—so many dancers do. Not Robbins. Even in his late fifties he could easily demonstrate complex steps and turns for his dancers. In his later ballets—Dances at a Gathering, Goldberg Variations, and Watermill—he relaxed and showed how “naturally” he could choreograph. He coached both Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov, superstars who defected from the USSR. This writer recalls Robbins cruising through Rizzoli Bookstore’s mirrored chambers at night with the grace of a predator, his tanned face, framed in full white beard, making him resemble some mythological Pan or satyr.

These writings reveal not only the brightness of his creative life—his thrill at the legendary Igor Stravinsky, whose Circus Polka he choreographed and who called him “Jerry”—but also its shadowy underside. It quickly becomes clear that even with all the fame and glory, Robbins had serious “issues.” For all the love he gave, he was never able to keep a lover. While he lived with several women for years at a time, he simultaneously cruised gay spots. Seemingly a true bisexual, later in life Robbins gravitated toward comely younger men, with all the complications that brought. Yet when Village Voice columnist Arthur Bell wrote an encomium for Back Stage to those gay men who built the American theater, Robbins was infuriated to be named, and threatened to destroy Bell‘s career.

Then there was the issue of his Jewishness. Robbins loved his family and adored his father, going so far as to conceive, direct, choreograph, and dedicate Fiddler on the Roof to the older man. Yet in times of stress, he used his Jewishness in his journals to excoriate himself, calling himself a “Jewish kike.” This was not a common sentiment for Jewish artists at this time. Bernstein, for example, far from being tortured by it, was openly proud of his Jewish heritage.

More torment came from earlier events in Robbins’ life, when he was forced to make a decision regarding the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). It’s true that he had joined the Communist Party as a youth, but he soon became too busy to have anything to do with it. But then, at a crucial moment in his career, the powerful anti-Communist newspaper columnist and later TV host Ed Sullivan got word of it and threatened to expose Robbins, who went directly to the FBI and turned himself in. It’s unclear what names Robbins was able to give up, since he was so distant from the party. But he did so, he reminds himself in a journal, because his family’s shtetl philosophy was to “do whatever is necessary to survive.” And while he never had proof that he’d harmed anyone, he remained torn by guilt.

Time passes, and other troubles become apparent. While his health remained good and he lived until the age of eighty, he was losing the people he had idolized, such as Balanchine and his father, and then many more of his age mates and professional colleagues. It’s not really surprising to learn that he checked himself into a hospital claiming “exhaustion”—like a machine that had run down—only to die a day later from a massive stroke.

Felice Picano’s latest fiction is Justify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts (Beautiful Dreamer Press).