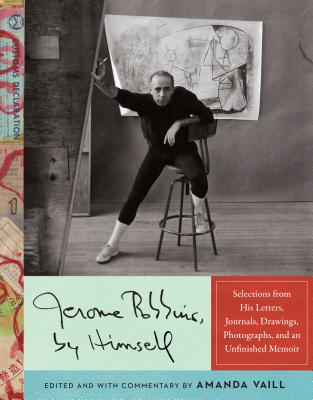

Jerome Robbins by Himself: Selections From His Letters, Journals, Drawings, Photographs and an Unfinished Memoir

Jerome Robbins by Himself: Selections From His Letters, Journals, Drawings, Photographs and an Unfinished Memoir

Edited by Amanda Vaill

Knopf. 399 pages, $40.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION did major damage to American society, but for at least one individual, it proved exactly the kickstart he needed for his genius to flower. Born in 1918, Gershon Wilson Rabinowitz had intended to study “politics or economics maybe” in college. Instead, when he graduated from high school, he discovered he had to go to work. He found all kinds of jobs and eventually found work dancing, something he’d enjoyed doing at school. Soon he ended up in a small dance company called the American Ballet Theatre.

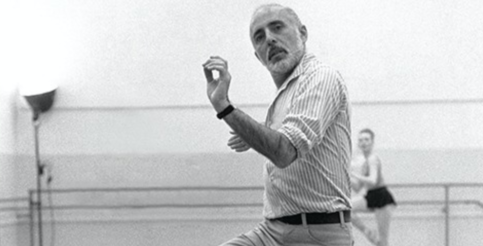

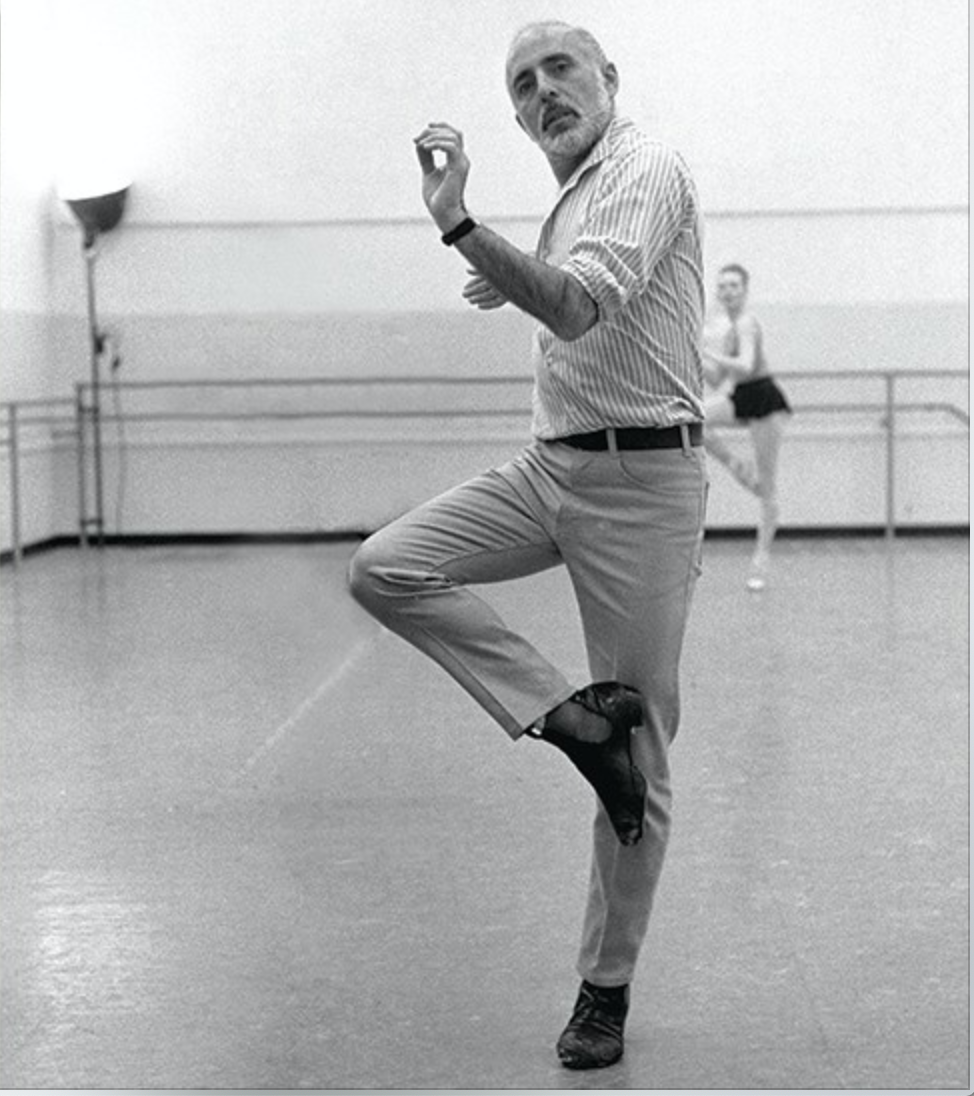

Those three words sum up what he quickly became when he moved to Manhattan as an American ballet dancer and a choreographer named Jerome Robbins. As a dancer, he shouldn’t have been exceptional: he was below medium height and thin, but he was flexible, with reserves of energy, and unafraid of hard work. Above all, he had ideas—lots of them. By the age of 26, he had met many other eager young American neighbors in the West Village: dancers, composers, writers, and theater people. World War II was raging, and he proposed a short ballet about three sailors on leave in New York. His neighbor, Leonard Bernstein, liked the idea and composed a dance score that Robbins choreographed. Their hip, contemporary, almost casually stylish Fancy Free was an instant hit. It brought both young men fame, as well as the ability to turn it into a full-fledged Broadway musical. On the Town opened the following December and was also a hit. Robbins’ vibrant new style of dance-making led to offers to choreograph more musicals, including Look Ma, I’m Dancing and High Button Shoes. Eventually he would direct and choreograph twenty Broadway shows.

Robbins moved on to dance for the newly formed New York City Ballet, which, under George Balanchine, would soon outstrip the French and Russian schools to become the ballet company of the century. His idea for a contemporary Romeo and Juliet, with Bernstein composing again, opened in 1955 as West Side Story. With its athletic, violent, sociologically complex, openly ethnic and sexual elements, the musical mesmerized Broadway and the dance world. Soon Hollywood would call, and Robbins would tentatively work there too, creating nearly authentic Asian dances for The King and I, all the while continuing to tend to his multiple home fires. The amazing pyrotechnics of Russ Tamblyn and his six male cohorts in the film Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, or of the waiters in Streisand’s Hello Dolly—high points in filmed dance—became possible only after Robbins had liberated the male body on stage and screen and wildly expanded its reach and its depth.

Felice Picano’s latest fiction is Justify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts (Beautiful Dreamer Press).