“Unpersons” of the Past and Present

To the Editor:

Trevor Duncan complained in a recent letter [Jan.-Feb. 2012] about the conspiracy of silence surrounding pederasty in gay publications. The matter goes far deeper than that. I wish to point out the similarity between the treatment of pederasts in the homosexual community and the treatment of polygamists in the Mormon community. In the 19th century, most if not all Mormon men were polygamists. But beginning in 1890, under pressure from the federal government, polygamy was abolished or went underground. The remaining polygamists were expelled from the LDS church. To this day there are a number of breakaway sects that practice polygamy, which are not recognized by the main church.

In exactly the same way, beginning in 1977, the homosexual community began rejecting and expelling the pederasts, even though pederasty had once been the dominant or even exclusive form of male homosexuality. It is easy and convenient to forget that pederasty only a few decades ago was still accepted in the homosexual community to a degree now considered astonishing. Edmund White, for example, in his book States of Desire included a section on a pederast without the slightest hint of disapproval. I could also draw a parallel, perhaps grotesque, between this and the expulsion of the Trotskyites by the Stalinists. What we have now within the homosexual community is a form of air-brushing in which the pederast disappears from the photo, becoming what Orwell called an “unperson”—someone who ceases to be mentioned and whose very existence is denied. The dominant position today is to assert that pederasty is not a form of homosexuality.

Stephen W. Foster, Miami, FL

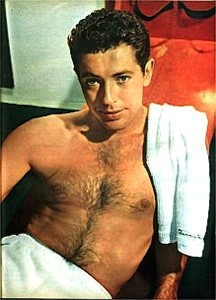

Farley Granger Omitted from 2011 Obits

To the Editor:

Reading your list of gay artists who passed away last year [Jan.-Feb. 2012], I was miffed to see that Farley Granger (1925–2011) wasn’t among them. Granger was perhaps best known for his roles in  Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense classics: as tennis pro Guy Haines in Strangers On a Train and as Phillip Morgan in Rope (with a screenplay by his one-time lover Arthur Laurents). He played opposite Robert Walker as the psychotic, “effete,” mother-fixated Bruno Anthony, who suggests that they plan the perfect crime by swapping murders, with Bruno killing Guy’s wife and Guy disposing of Bruno’s father. As in Rope, there was a homosexual subtext to the two men’s relationship, although it was toned down from Patricia Highsmith’s original novel. In Rope, which was loosely based on the infamous Leopold and Loeb “thrill killing,” Granger and John Dall played university students scheming to murder their “inferior” classmate, hide his body in a trunk, and invite friends and family to a “chic” dinner party with the corpse stashed in the makeshift coffee table. (John Dall even plays Poulenc on the piano!)

Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense classics: as tennis pro Guy Haines in Strangers On a Train and as Phillip Morgan in Rope (with a screenplay by his one-time lover Arthur Laurents). He played opposite Robert Walker as the psychotic, “effete,” mother-fixated Bruno Anthony, who suggests that they plan the perfect crime by swapping murders, with Bruno killing Guy’s wife and Guy disposing of Bruno’s father. As in Rope, there was a homosexual subtext to the two men’s relationship, although it was toned down from Patricia Highsmith’s original novel. In Rope, which was loosely based on the infamous Leopold and Loeb “thrill killing,” Granger and John Dall played university students scheming to murder their “inferior” classmate, hide his body in a trunk, and invite friends and family to a “chic” dinner party with the corpse stashed in the makeshift coffee table. (John Dall even plays Poulenc on the piano!)

Granger also starred opposite Alida Valli as the disreputable Franz Mahler, an Austrian soldier in occupied Venice during the Risorgimento in Visconti’s historic epic Senso. Later, he moved to New York, where he worked onstage as John Proctor in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. He played opposite Barbara Cook—with whom he maintained a life-long friendship—in a revival of The King and I at City Center, starred with Marian Seldes in Deathwatch, and appeared with Marian Seldes in Talley & Son, by Lanford Wilson.

I interviewed Granger once in his home on the Upper West Side after the 2007 publication of his memoir, Include Me Out, My Life from Goldwyn to Broadway, co-authored by his lover Robert Calhoun. In the book he discussed his bisexuality and his affairs with Ava Gardner, Leonard Bernstein, and Shelley Winters, who was “the love of my life and the bane of my existence.” About Rope he observed: “Arthur [Laurents] made sure that I was aware of what he felt was going on between the between the characters, and, of course, John Dall and I discussed the subtext of our scenes together. We knew that Hitch knew what he was doing and had built sexual ambiguity into his presentation of the material.” He also knocked the homophobic Hollywood system, whose smarmy suits advised him not to fraternize with composer Aaron Copeland lest he be branded as queer. He outed “all-American boy” Van Johnson, who was forced into a studio-arranged marriage.

He met Bob Calhoun, who died in 2008, while doing a National Repertory Theater tour for which Calhoun was production manager. Asked about his preferences in the 2007 interview, Mr. Granger said, “I’ve lived the greater part of my life with a man, so obviously that’s the most satisfying to me.” During our interview, it was touching to see how close the two men were, with Bob finishing many of Farley’s sentences and reminding him of dates and names. I also had the chance to tell him how I had a crush on him as a youngster watching him as the dance master in Hans Christian Anderson on TV. It turns out the whole production was a nightmare for him due to the obnoxious behavior of Danny Kaye.

Born in San Jose, Cal., Granger morphed into the consummate New Yorker. He died in New York, of natural causes, at age 85.

Michael Ehrhardt, Roseland, NJ

Kameny’s Military Discharge

To the Editor:

The interview with Frank Kameny in the current issue [Jan.-Feb. 2012] contained a glaring error. The introduction to Amin Ghaziani’s interview [conducted in 2003]describes his early career as follows: “Having received a doctorate in astronomy from Harvard in 1956, Kameny was soon drafted into the U.S. Army, from which he was discharged in December 1957.” Kameny served in the Army during WWII and fought in Europe. As such, he was not drafted by the Army in 1956, but in the early 1940’s. It was not until 1957 that he was discharged from the Army Mapping Service, where he worked as a civilian astronomer, for being gay.

Ray Gaut, Arlington, VA