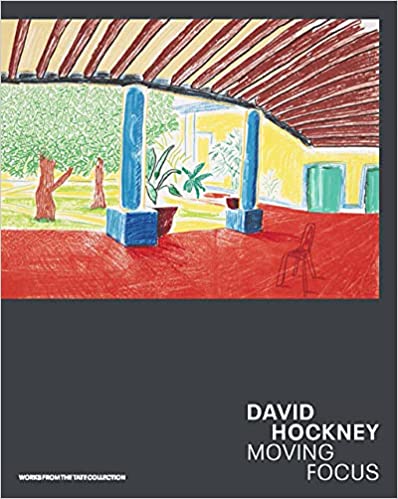

DAVID HOCKNEY: MOVING FOCUS

DAVID HOCKNEY: MOVING FOCUS

Edited by Helen Little

Tate. 224 pages, $50.

BORN IN Yorkshire, England, in 1937, David Hockney grew up humbly but distinguished himself from his peers at an early age through his talent and ambition. He entered London’s Royal College of Art as someone to watch, and he left a star. His work from the 1960s is cryptic, but the muddied, abstract canvases offer clues—fragments of text, including lines from Whitman, and images of male nudes—as to what he was thinking about. He created his own visual identity with his signature round glasses and a shock of bleach-blond hair.

This new look was perfect for Los Angeles, where, inspired by the clear light, he painted simple forms, most famously swimming pools (and the men in and around them). In the 1970s, Hockney began painting huge, realistic portraits of couples. While the subjects are casually staged in domestic environments—slouched in chairs, leaning in doorways—their near life-size scale makes them feel epic. The paintings have a dreamlike quality, the subjects somehow suspended in both space and time.

A new monograph, David Hockney—Moving Focus, memorializes not only the illustrious career of one of the world’s most famous artists but also the Tate Museum’s supporting role in it: first as a source of inspiration to a young artist, then as the benefactor of a rising star in the art world, and finally as a keeper of the artist’s legacy. The book’s editor, Helen Little, an art curator at the Tate, has pulled together a diverse collection of 22 essays by various artists—an actor, a poet, a dancer, an opera director, and so on—to testify to Hockney’s influence on their work. Many of their essays offer little slices of the artist’s biography and touch on the things that captured Hockney’s eye at a given moment or over a period of time, highlighting what Little calls Hockney’s “principal obsession with the challenge of representation: how do we see the world, and how can that world of time and space be captured in two dimensions?”

In the 1980s, Hockney started experimenting with a range of styles, including Cubism. According to Catharine Cusset (author of Life of David Hockney: A Novel and a contributor to the book under review), Picasso was one of Hockney’s two major influences. The other big influence on this gay man was—surprise!—his mother, who supported his interest in art from an early age and frequently served as his model. After her death, Hockney painted, en plein air, the views she’d once enjoyed in the Yorkshire countryside. (Hockney’s recent output has been largely digital, including drawings done on an iPad.)

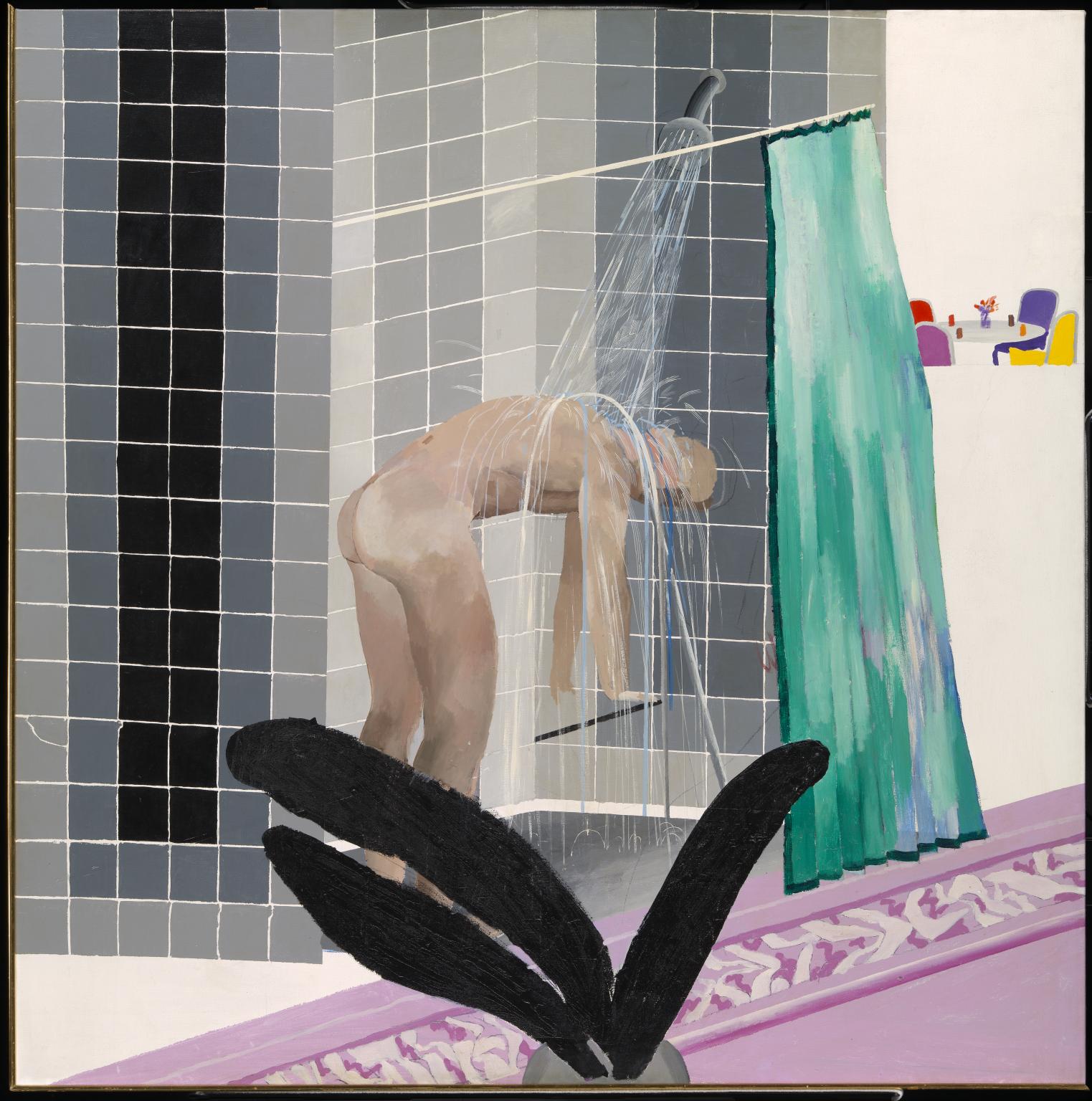

The essays in David Hockney are a mixed bag. Some are academic, such as art lecturer Gregory Salter’s analysis of Hockney’s work in relation to 1960s queer history. Some offer personal recollections, such as the artist Ed Ruscha recalling Hockney zipping around L.A. in a convertible (“top always down”). To me, the most interesting essays offer a deeply personal response. Painter Christina Quarles picks a painting, Man in Shower in Beverly Hills, and helps us to understand what we’re looking at: a naked man bent over in a tiled shower, water splashing on his back, his head turned toward us. But what’s important to notice here, Quarles suggests, is not the man’s position but Hockney’s vantage point as the viewer: crouched down low, peeking out from behind the silhouette of a potted plant in the painting’s foreground. With an understanding of this perspective, the painting is transformed into “a scene not only of looking but of being found out.”

For those unfamiliar with Hockney, this book may not be the best place to start. It’s a little like walking in on a conversation about a person everyone assumes you already know quite well. Looking at some of the pictures here, you may wonder what all the fuss is about. Others may be confused by his many changes of style or be repelled by his naked bid for relevancy as an artist. Die-hard fans will no doubt find their appreciation for Hockney confirmed.

Michael Quinn reviews books for literary journals and in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue.