Cloudburst

Cloudburst

Directed by Thom Fitzgerald

(Canada, 2011)

North Sea Texas (Noordzee, Texas)

North Sea Texas (Noordzee, Texas)

Directed by Bavo Defurne

(Belgium, 2011)

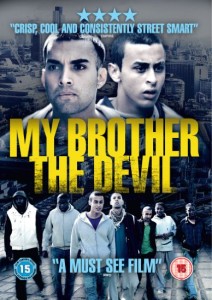

My Brother the Devil

My Brother the Devil

Directed by Sally El Hosaini

(United Kingdom, 2012)

NEW YORK’s GLBT film series, NewFest 2012, was a milestone this year. The East Coast organizers have partnered with Los Angeles Outfest, and programming was held at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater in cooperation with the Film Society of Lincoln Center. As GLBT cinema becomes increasingly professional, it is fitting that the Walter Reade, with one of the best projection and sound systems in New York City, should become the hub for NewFest’s offerings. Will a larger public follow, including both a growing gay and non-gay audience? In any case, this year’s films suggest that even what we call “queer” cinema is in flux.