“FIFTY YEARS after Stonewall.” “Stonewall: Fifty Years Later.” “Stonewall Turns Fifty.” “After Stonewall: Where Are We Today?”

These are bound to be some of the titles to various think pieces and short history primers that will fly around for the next few months, each aimed at our collective consciousness and designed to make us remember, remember, remember an event that’s rapidly fading out of public memory but becoming memorialized in very particular and often hagiographic ways. The hype will be endless, as will the tears. Everywhere we go, we’ll run into people who’ll tell us that they were “at Stonewall,” when they might actually mean, “I was many miles away but I was somewhere in the state of New York, around that time, sort of.” For many years, one particular lesbian activist, firmly ensconced as an “elder,” would insist that she be introduced at the events she spoke at as a “Stonewall veteran,” a mystifying claim to all who knew she’d been a Chicago native all her life. If you probed further, you found out she’d actually been at Woodstock, later that summer, and had taken to mentioning Stonewall to give herself even greater street cred.

All of which is to say that Stonewall is a contested piece of history, and its exact contours and politics remain open to interpretation depending on who is doing the writing (or rewriting) of the riots. But fiftieth anniversaries are a huge deal—Golden, after all—and Stonewall’s will be written about a million times before the end of June is here. And yet, I can’t help but roll my eyes at all the celebratory and self-congratulatory discourse around Stonewall. As the anniversary approaches, forging ahead like a juggernaut smashing every other puny bit of queer history along the way, I wait, exhausted, my arm over my forehead in a pose so often taken in portraits of Victorian women on fainting couches and wonder, Is it over yet?

Because, really, I’m sick of it all, sick of constantly having to point out that Stonewall was not the moment that inaugurated modern gay history everywhere, or to state yet again that it was in fact a bunch of rowdy, kick-ass, and ass-kicking drag queens and cross dressers and trans people who inaugurated the moment that supposedly upended LGBT history as we understand it. Mostly, I’m sick of having to think yet again of Stonewall as Stonewall. I’m weary of having this moment foisted upon me as if it were a Queer Independence Day, as if on June 28, 1969, my cultural DNA as a queer person was suddenly and radically altered, as if that date should be seared across the minds of not just American queers but queers everywhere.

Consider, for instance, an op-ed by the gay Indian man who calls himself Prince Manvendra Singh (India is no longer ruled by monarchs, petty or grand, but his title clearly endears him to eager Western audiences), where he writes that “India has still not yet reached the stage of the Stonewall riots in the US.” It’s easy to mock Singh, with his preening ways and his strange (but clearly well-aimed, at audiences outside India) way of projecting a pre-colonial image that is neither liberatory nor too complicated but straight out of a comic book about some fabled Indian prince. But his words, in all their simplistic glory, reflect a larger cultural sense that every gay community across the world has to have a Stonewall moment, when the queer denizens of a land get fed up with restrictive laws and take matters into their own hands (and to be fair to him, the novelist and writer Sandip Roy has an equally reductive take on India’s gay history as culminating in gay marriage). Consider, for instance, that Britain’s largest LGBT organization is named Stonewall (in an interesting reversal of the usual dynamic where a former colony apes the colonizer). And Stonewall, the actual inn, now an official tourist site, is designated the “birthplace of the modern LGBT rights movement.”

But there are several problems with positioning Stonewall in such ways. Among them is that it ignores that riots and insurgencies of all sorts happened before 1969, such as the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot in 1966 in San Francisco or the raid on the Trip bar in Chicago in 1968. Unfortunately, even such fresh records end up reiterating the popular mythology about LGBT lives and histories: that they come into being most profoundly in cities.

We should, of course, admit and acknowledge that urbanization does in fact allow, in complex ways, for several kinds of identities and new lifestyles to flourish. Gay historians have documented how entire new queer cultures (not just “sub” cultures) have found their ideal habitats in cities because the spaces afforded so many the right to be anonymous among throngs, to venture into new ways of being away from the probing eyes of families and neighbors. But, as Ryan Conrad points out in a remarkable forthcoming piece in QED (Issue 6.2, 2019) titled “I Still Hate New Year’s Day”:

No one has mapped the network of back-to-the-land lesbian homesteads in Down East Maine that have been there since at least the 1970s. No one has written about the bilingual, bi-national Northern Lambda Nord newsletter that was published regularly between 1980 and 1999 servicing Acadian and indigenous queers living in Northern Maine, Eastern Quebec, and Western New Brunswick. And still, no one defends the men who continue to be periodically busted for indecency while cruising the truck stop off the rural highway just outside my hometown, as they aren’t the proper queer subjects that identify as gay, don’t necessarily have a strong interest in liberal gay politics, or participate in urban gay cultural events like Gay Pride. Somehow the mythical history of the Stonewall Riots takes precedence.

Even those of us who are ferociously urban queers can and should appreciate the fact that the erasure of such currents of the past and present does no favors to LGBT people, but instead keeps them trapped in an endlessly repetitious reel of sexual disenfranchisement as well as economic marginalization. The idea, too popular among historians and commentators and the public at large, that queer life is only truly queer once it escapes rural areas is part of a larger cultural perception that non-urban areas simply don’t matter and don’t deserve resources. We can consider the vibrancy of non-urban life without fetishizing it as more authentic (or more adorable). And, in considering it as equally if differently vibrant, we might begin to slow the material depredations that non-urban areas in the U.S in particular have seen for so long, including the loss of basic infrastructure like public transportation (try taking an hour-long bus trip to the only gay bar in a small town on a cold December night: desire dies fast in the freezing air) and much-needed healthcare (if you’re trans and/or queer and need LGBT-sensitive healthcare, your only choice sometimes is to take a days-long trip to the nearest large city, and that’s if you’re lucky). Over the last many decades, we have naturalized the idea that the most significant resources (or the resources that get us, literally, to the places we want to get to) need only be portioned out to urban areas because, after all, who lives anywhere else?

The problem with this urbanization of lgbtq history isn’t simply that it takes attention and resources away from non-urban areas, but that in further reifying the idea of the urban as essentially liberatory, it persuades onlookers of and participants in “gay history” moments that they are simply about gay and lesbian identity (the B, the T, and the Q are shunted aside) and that notion of identity is immersed purely in emotion these days, and of course that emotion is love—the only thing that defines anything remotely queer. In the process, the larger public is persuaded to forget (if it ever knew) that gay and lesbian identity is in fact part of a larger framework of public life, surveillance, and the incursions of the state.

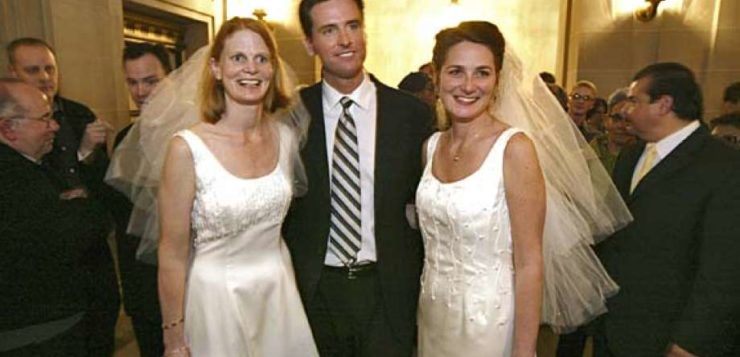

Photo: Kim Komenich. San Francisco Chronicle, Jan. 2, 2005.

Consider San Francisco, where in 2004 the newly elected mayor Gavin Newsom opened the floodgates to gay marriage, as the lore goes, by allowing for same-sex marriage licenses to be issued, something that went on for a month and resulted in thousands of gay couples flying into the city to get married. The San Francisco event would be among the first of several that cemented Gavin Newsom’s reputation as a major progressive figure. At the time, he was only a month into his first term as mayor, and the issuing of marriage licenses allowed him to gain favor with San Francisco’s conservative and financially powerful gays and lesbians, who had enormous influence in the city. These were many of the same people who encouraged the tech industry to enter the city and caused the massive housing crisis which has led to a stark and inexorable shift in the very nature of the city. Ironically, or perhaps not so ironically, the “massive” rallies for marriage licenses became part of the eventual erasure of a different kind of queer history, an insurgent one marked by a refusal to live by straight norms like marriage. We can never be too cautious about an overly sentimental and nostalgic rendition of the past, but we can state with some confidence that the rise of gay marriage in San Francisco inaugurated one era of LGBT history while erasing another.

THIS BRINGS US to the aftermath of gay marriage, something that is still seen as the very apex of gay movement history. Much like Stonewall, Edith Windsor’s win in the 2013 United States v. Windsor case is considered the moment when the walls of inequality were finally smashed, a moment that helped make it possible for gay marriage to become legal everywhere. Windsor, with the help of organizations like Lambda Legal that were looking for the right plaintiff to head up their cause, initiated the lawsuit because, as someone not legally married to her wife Thea Spyer in the U.S. (they had married in Canada in 2007), she had been made to pay $638,000 in estate taxes. Edith Windsor, the story went, was being punished for a lifetime of loving another woman.

But what has that win meant, and for whom, and what was the real story of Edith Windsor? For the years immediately preceding the lawsuit, Windsor’s lawyers subtly disseminated the idea that she was a penurious widow, perhaps striking matches in a drafty New York apartment to stay warm. Many in the media uncritically bought the idea and some carefully avoided giving away the figures of her taxes. But no one revealed the truth until the case was decided: that the taxes she paid were only a small percentage of an estate that was worth about six million dollars. In fact, only a tiny percentage of the population has to pay such large taxes, and it’s only because they inherit such large estates in the first place. What Edith Windsor was fighting against was not an unjust system that would leave her impoverished but the right to not pay taxes on a substantial inheritance. It was only after the dust had settled on the 2013 lawsuit that The New Yorker finally published an exhaustive profile of Windsor, one that openly discussed her wealth and ended with her contemplating buying a house in much the way one might go antiquing.

The point here is not simply that the whole story of Edith Windsor was deliberately painted as that of a woman who could have been “one of us,” thereby inviting greater sympathy among straights, gays, and lesbians alike. Establishing this as a landmark case (the phrase used often by media outlets and commentators) and as a singular point in history, much like Stonewall, allowed the conservative gay movement to occlude the real beneficiaries of gay marriage: wealthy gay men and women who are finally allowed, legally, to turn their riches into wealth that can be passed on, much like straight, wealthy people can. Anyone can make money, but only the wealthy get to turn their money into estates.

Let us call this, with a bad pun, the Stonewalling of gay history: establishing that a particular event or person, or conjunction thereof, is purely and exclusively about gay identity and gay love as popularly construed, thereby erasing the many economic, political, and cultural complexities and complications that surround it.

What if, instead of memorializing Stonewall and Windsor (whose face appeared on T-shirts in the 2013 Chicago Pride parade with the words “I AM Edith Windsor”), we chose to forget them instead? What would it mean to forget Stonewall, especially in this year, the Golden Anniversary of the event?

To “forget Stonewall” would not mean to erase the fact that it happened, in all its glorious insurgent ways, but instead to begin to think about building and weaving very public histories of not only who was involved (by now, even mainstream publications acknowledge the riotous presence of fierce drag queens and other hitherto forgotten and marginalized figures, to an extent) but what was involved. Instead of plaques and commemorative texts instantiating Stonewall as the “Birth of the Modern Gay Movement,” we might instead consider promulgating histories of the gentrification around the Inn and the often rapid erasure of sexual cultures, including the cinema houses immortalized by Samuel Delany in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. In too many ways, even the recent recuperation of drag queens and trans people is a part of that myth-making: If we simply remember that such bodies existed, we’re okay, we tell ourselves, and we continue onwards, smug in our sense that we have somehow resisted the power of the state.

But we might, instead, consider that none of that recuperation of history, the retelling of sacred names once forgotten (the sort that simply asks us to “remember” Edith Windsor’s name), actually gets us to the much more intractable violence of the surveillance and brutality visited upon those who simply don’t count themselves as gay, the men, Conrad points out, who “aren’t the proper queer subjects that identify as gay.” In that sense, rather than fetishize the mythology of gay or queer history, even by remembering the once-forgotten, we might think of it as violence itself, because the constant injunction to remember history in mythic terms like Stonewall or Windsor disallows, erases, and inflicts state violence upon those whose bodies fall outside the now more protective rubric of “gay” or “queer.”

We might consider events like the Compton’s Riot and the Trip raid as interwoven with the histories of cities that also witnessed white flight and, in the case of Chicago, a virulent form of plantation racism that means that gay bars and neighborhoods in that city, where I live, are marked by intense forms of policing and surveillance over non-white bodies. We might stop reading moments in Indian queer history as potential Stonewalls but recognize that LGBT events and people in areas marked so heavily by colonialism and imperialism must and will have entirely different relationships, as it were, to issues like gay marriage. None of this evokes names but instead compels us to think more radically about the grip that seemingly abstract historical phenomena like Empire have upon us.

The point in forgetting Stonewall is to hold on to the much more difficult task of thinking about “event-ness” and history in more complicated ways. The point in forgetting history is to dismantle the very idea of remembering it as a series of events involving Very Important People or Those Who Were Once Forgotten. To forget means to constantly live in the tension of history rather than within its planed-down, reductive version. To forget Stonewall is to ask for a constant recalling, always, of the violence of the state upon those who remain unprotected by the myths of historical memory.

_________________________________________________

Many thanks to Ryan Conrad, Richard Hoffman Reinhardt, and Matt Simonette for reading and contributing points to this piece; any remaining problems are mine alone.

Yasmin Nair, an academic and a writer, is a cofounder of the radical queer editorial collective Against Equality. She maintains a website at www.yasminnair.net.