Studio 54

Studio 54

by Ian Schrager

Rizzoli International Publications

396 pages, $75.

THE MOST striking feature of Studio 54 is its heft: Amazon lists the shipping weight as 8.2 pounds. Almost any page of this substantial publication confirms what people already know about the legendary nightclub: that it was a playground for celebrities, a temple for disco, and a brand of spectacle not seen before in a nightly venue. This highly predictable intersection of themes raises the question: unless you yourself frequented the club, why invest in this tribute to the best nights of someone else’s life? Still, the rewards of this volume are numerous, although they partly depend on the version of gay life with which one identifies. And that question begins with New York’s role as the one-time mecca for gay men.

David Carter’s Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution cogently opens the story of gay migration to Manhattan with Greenwich Village’s refusal in 1817 to conform to the grid that reshaped most of the borough. But the Village’s ability to be the destination of nonconformity is hard to imagine without a surrounding city of industry, which thrived precisely because of a coordinated infrastructure. The story of Studio 54 is that same paradox of chaos married to order, bohemians hobnobbing with establishment titans. The club’s very name, in contrast to London’s aspirational “Heaven,” mundanely announced its spot on the grid, 254 W. 54th Street. The club’s founders were Ian Schrager, now a hotel investor whose imprimatur lends this volume a definitive quality, and Steve Rubell, a restaurateur turned promoter who died from AIDS-related causes in 1989. By outward appearances at least, Rubell’s role within the club was to be the anarchist to Schrager’s voice of reason. Either Schrager didn’t see it that way or he wasn’t an equal force, since the two eventually landed in prison for tax evasion, ending the club’s three-plus years (1977–’80) as the world’s most celebrated discotheque.

But this brings us to the first reason this book is worth the investment: its complete refusal to apologize. Nearly every other treatment of 54’s history, from books to television documentaries to the unfortunate 1998 film, seemed to insist on using the pair’s incarceration, Rubell’s death, and disparaging takes on the era’s excesses as tragic allegory. Schrager’s book offers not one paragraph of remorse. Among its many self-justifying visual hallmarks: Teddy Pendergrass seated at a piano and duetting with Stevie Wonder; Liza Minelli cutting a rug with Mikhail Baryshnikov; Bianca Jagger being led into the club on horseback by a fully naked man whose formal tie and tails were a grease-painted illusion; and, perhaps most dazzlingly, Richard Gere in an immaculate white suit being led onto the dance floor by Diana Ross. Ross is clad in jeans and a ragged tanktop that reads “no swet,” wearing not a trace of makeup, all of which coalesce into a sprezzatura glamor that only a true diva could pull off.

The combinations of celebrities are often more interesting than the stars themselves. The questions these images provoke almost sound like the beginning of a riddle: What did Michael Jackson say to Steven Tyler? Farrah Fawcett to Cary Grant? Leonard Bernstein to Jackie Onassis? Eartha Kitt to Gloria Swanson? Coretta Scott King to … anyone? The book also has its share of fun with these pairings, and the tumult that lay ahead for them. Farrah is identified alternately as “Fawcett-Majors” and as “Fawcett,” and shown in one photo with her subsequent life partner Ryan O’Neal despite still being married to Lee Majors. Mick Jagger is with Bianca Jagger in one image and with girlfriend Jerry Hall on the opposite page. O. J. Simpson appears with fellow footballer Marcus Allen, who was later rumored to have had an affair with Simpson’s wife Nicole.

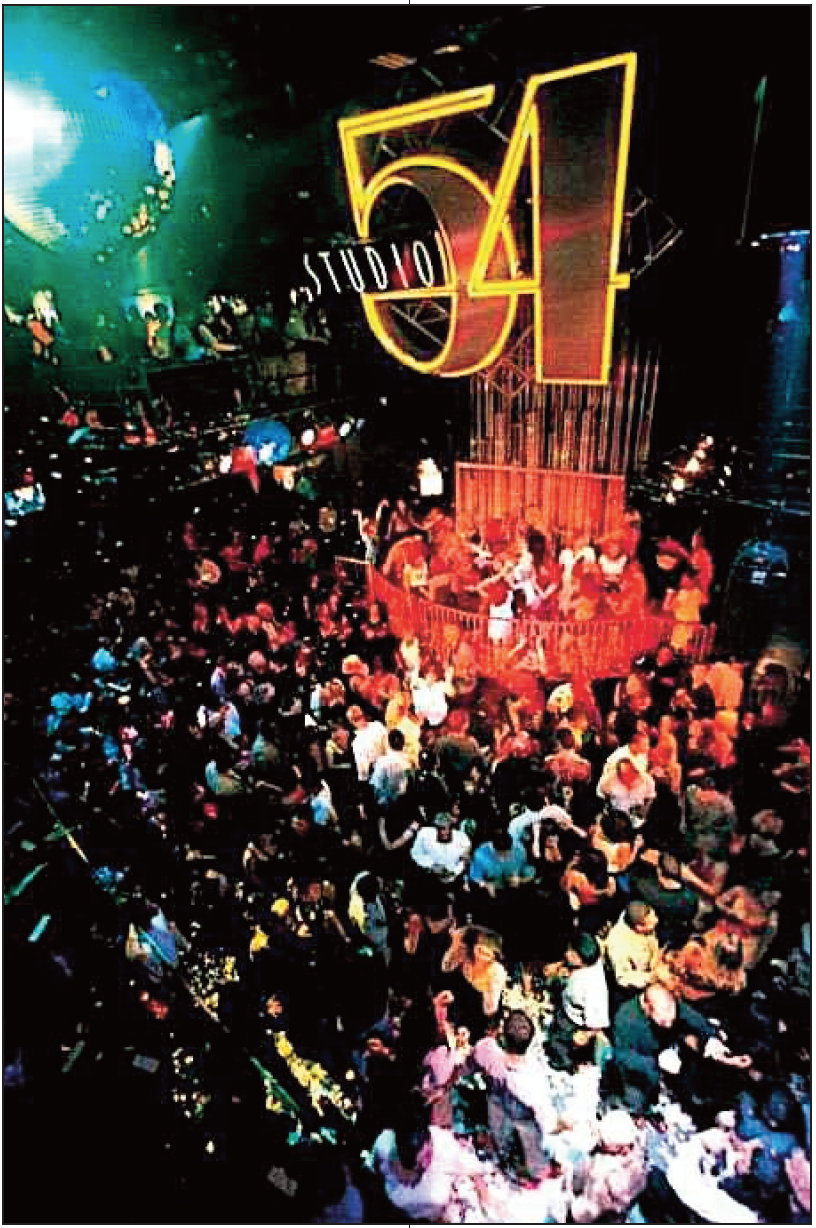

For the roughly two generations of gay people who came of age in the era of disco and house music, however, the magic of this book lies not in celebrity but in anonymity, of assimilating into sweat-drenched crowds where sexual difference made us the same. That legacy does not appear to be lost on Schrager. An equal share of the photos is given to gay or curious masses who came to the club to grant each other permission to misbehave on a grand scale. Some photos, like one of an Adonis in a jockstrap sodomizing himself with the leg of a chair, are there to excite or perhaps to appall. But there are just as many pictures of people doing what in New York in the ’70s became ordinary for the first time: dancing in whatever combinations and clothing (or lack thereof) they wanted.

After serving their sentences, Rubell and Schrager paired once more to build another dance temple, the Palladium, which was bigger than the 54, more inclusive, and enjoyed much greater longevity. It magnified the legacy of the 54 because, what it lacked in elephants, horses, and coked-up celebrities, it made up for with visual and sonic architectures on an epic scale. In this way, it symbolically preserved the 54’s spacial concept, where music and lights merged to make life feel glamorous, even without a Jackson or Onassis stopping by.

Studio 54 memorializes other things that glossier documentaries forget. Several pages preserve the architecture from initial construction through later redesigns, the cover art and liner notes for an LP mixed at the club, and the posters and invitations that were once the promotional staples of an era before e-mail and Twitter. For many of us whose formative coming-out memories are tied to the countless nightclubs now shuttered, those items are often all we have left.

Although Schrager is listed as the only editor here, he is undoubtedly aided by the journalistic acumen of Bob Colacello and Paul Goldberger, both Vanity Fair contributors who have foreword essays here. In a prefatory interview with Schrager, Goldberger offers one of the book’s most poignant observations. Speaking of the crime and decay that marred New York when the club opened, he notes: “The parts of the city that respectable people would go in, it was a much smaller place. … Now, those [feared]blocks, the houses are selling for $10 million in those areas. The neighborhoods people once wouldn’t walk in, they now can’t afford.” The cruel irony of gentrification is that marginalized people take the world’s unwanted spaces and elevate them into cultural zones that the marginal can’t afford. At this price point, perhaps even this book is such a zone. But like all the other sacrifices LGBT folk made to find one another on the dance floor, it is well worth the price.

Ken Stuckey is a senior lecturer in English and media studies at Bentley University.