BEGIN AGAIN

BEGIN AGAIN

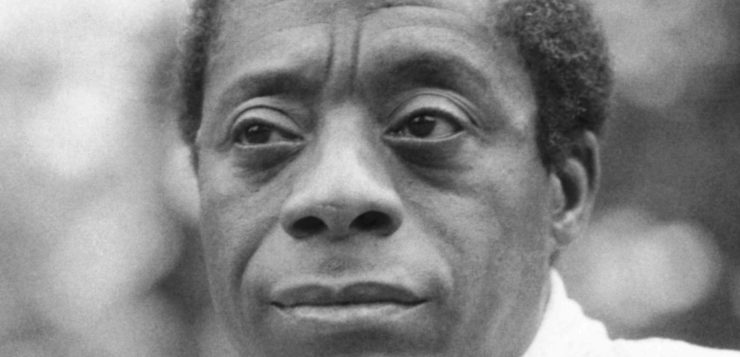

James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own

by Eddie Glaude, Jr.

Crown Publishing. 272 pages, $27.

JAMES BALDWIN was barely out of junior high school when he began his career as a minister in the Pentecostal churches of Harlem, but, as he describes in The Fire Next Time (1963), his quick ascension to those ranks had the ironic effect of estranging him from religion: “Being in the pulpit was like being in the theatre; I was behind the scenes and knew how the illusion was worked.” He fled the church and, with some guidance from the gay painter Beauford Delaney, took his first steps toward becoming a secular prophet—as a freelance essayist, then as a novelist, and then as a public intellectual. The pressure of being a gay black public figure in America’s era of assassination took its toll on his writing and his health, and when he died at 63 in 1987, he was still respected, but his literary profile had been at half mast for some time.

Several factors, including our regrettable return to racial violence, have spurred a spate of Baldwin-inspired works, including: Raoul Peck’s Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2016); Barry Jenkins’s Oscar-winning adaptation If Beale Street Could Talk (2018); and the acclaimed Ta-Nehisi Coates book Between the World and Me (2015), which should strike savvy readers as a conscious tribute to Baldwin. Now Princeton scholar Eddie Glaude, Jr., contributes Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own. Glaude extends Peck’s portrayal of Baldwin as a prophet of the Black Lives Matter movement. Peck’s documentary only guessed at the racial strife of Donald Trump’s imminent regime, while Glaude fully surveys the dangers of Trumpism, linking it to the putatively more benign conservatism of Ronald Reagan: “What we are living through … is not unlike what Baldwin and so many others dealt with as the black freedom movement collapsed with the ascent of the Reagan revolution. This latest betrayal by the country joins with the underlying trauma caused by all the previous betrayals.”

Glaude summons disparate writing modes to accomplish his aims. The strongest is literary biography, in which he chronicles Baldwin’s hopes for the country that were always paradoxically tempered by apocalyptic doom. This seems to match Glaude’s mood as he reckons with his own “egregious” misjudgment of America as incapable of electing Trump. He describes the current moment as the “after times,” a spiritual wasteland in which hope is not yet lost. He spends slightly too long rehashing Baldwin’s arguments, particularly No Name in the Street, which he champions as the equal to Baldwin’s bestsellers. He also spotlights some omissions in Baldwin’s account, shedding much needed light on how both conservative and radical black activists of the 1960s and ’70s shied away from Baldwin (and, he should have noted, from Bayard Rustin) because of his sexuality, a shameful moral failure that Baldwin consistently discussed in less judgmental terms.

Glaude summons disparate writing modes to accomplish his aims. The strongest is literary biography, in which he chronicles Baldwin’s hopes for the country that were always paradoxically tempered by apocalyptic doom. This seems to match Glaude’s mood as he reckons with his own “egregious” misjudgment of America as incapable of electing Trump. He describes the current moment as the “after times,” a spiritual wasteland in which hope is not yet lost. He spends slightly too long rehashing Baldwin’s arguments, particularly No Name in the Street, which he champions as the equal to Baldwin’s bestsellers. He also spotlights some omissions in Baldwin’s account, shedding much needed light on how both conservative and radical black activists of the 1960s and ’70s shied away from Baldwin (and, he should have noted, from Bayard Rustin) because of his sexuality, a shameful moral failure that Baldwin consistently discussed in less judgmental terms.

Glaude later describes a personal pilgrimage to Baldwin’s gravesite that strongly echoes Alice Walker’s 1975 Ms. magazine essay “Looking for Zora,” which has been credited with rescuing Zora Neale Hurston from obscurity. Glaude, like Walker, struggles to find Baldwin’s gravesite despite the fact that it’s supposed to be marked. He asks a group of idle young men about its location. They’re standing in the cemetery emitting the smell of marijuana, and one of them speculates that Baldwin might be near Malcolm X, whose grave he can locate. Instead, Baldwin turns out to be right behind where the men are standing. The account is an allegory: like the kids in “Looking for Zora,” the young men are within arm’s reach of history but are oblivious.

It is worth noting that the phrase “looking for” is a template later taken up by Isaac Julien in Looking for Langston (1989). This film takes an impressionistic look at the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance, of which Langston Hughes was the leading figure. This matters because, when one compares Walker, Julien, and Glaude, the weaknesses of Glaude’s book come into sharp relief. Glaude acknowledges that his text is a mixture of styles and impulses, but his strength is traditional scholarship. He seems dissatisfied with the scholar’s perch. He frequently refers to Baldwin as “Jimmy,” but this posture of familiarity feels unjustified. Moreover, Walker was an established writer in 1975, using her platform to exhume a forgotten artistic ancestor. The Hughes legacy was secure in 1989, while Julien himself was a struggling black gay artist with the wolf of AIDS at the door. Julien is “looking for Langston” not because Hughes is imperiled but because Julien himself is. This begs the question: Baldwin’s legacy is flourishing and Glaude is an Ivy League professor and a cable news celebrity; so what is Glaude “looking for”?

Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and James Baldwin were all black and queer. So were Walker and Julien, though Walker’s essay does not address this. Glaude earnestly presents himself as an ally in his text, but his identity, which he requires us to consider given the way he eschews the abstract voice of the scholar, sabotages his effort to achieve genuine intimacy with “Jimmy,” not because Glaude is straight, but because he takes too few risks.

Baldwin was not only sexually candid in his work but treated sexuality as the chief means by which he conquered the illusion of race. In No Name in the Street, he argues: “[P]eople do not fall in love according to their color. … This means that one must accept one’s nakedness. And nakedness has no color: this can come as news only to those who have never covered, or been covered by, another naked human being.” Later, he describes a powerful politician drunkenly “groping for my cock.” Glaude explains: “The powerful white man, who with a phone call ‘could prevent or provoke a lynching,’ lived a desperate lie, not only about race, but about his desire, and the result of it was that he could not genuinely love because he was blind to the actual human being right in front of him.”

Glaude’s primary discipline is religion, and when he refers to “the LGBT community,” one feels not only his estrangement but a prudishness only momentarily broken by Baldwin’s “cock” anecdote. Glaude is seeking kinship with a man who left the church to embrace his queerness and wrote about it his entire life. So when Baldwin refers to a “New Jerusalem,” it reads as metaphorical. When Glaude does so, it reads as doctrinal, and he evinces no awareness of this shift or the distance it imposes between him and Baldwin.

At the close of the book, Glaude observes: “The very thing I feared about him in graduate school, I experienced as a fifty-plus-year-old man. He exposes your private lies and forces you, because of his own relentless commitment to the examined life, to confront your deepest wounds as a precondition for saying anything about the world.” But at no point has he revealed what his wounds are. He is forthcoming about the flaws of Trump’s white supporters and even the precarious enabling of Democrats, whom he regards as ceding too much ground to the racist South. But he still appears regularly on the commentary show of Joe Scarborough, the affable ex-Republican who harshly criticizes Trump but remains a conservative and, like many reformed Republicans, becomes mealy-mouthed about endorsing Trump’s Democratic opponents. Where does Glaude stand in relation to Scarborough or to his wife and cohost Mika Brzezinski, whose saccharine optimism after Trump’s election is a serious blow to her credibility? Ultimately, the potential force of Glaude’s book is hampered by its reticence toward aspects of his own biography that he has either withheld or not fully processed.

J. Ken Stuckey is a senior lecturer in English and media studies at Bentley University.