PERUSING the Billboard Hot Soul Singles chart from the back issues of 1978, one has to be struck by the diversity that chart offers in contrast to today. The legacy of hip-hop, which was just being invented around that time, eventually eviscerated every other style of soul music such that Chris Brown, replete with tattoos and rap sheet for battery, is just about the most sensitive male artist on the current chart. (Pause and let that sink in.) But in 1978, on one chart, you could find hypermasculine lotharios like Rick James, Teddy Pendergrass, and Barry White; message men like Curtis Mayfield and Donny Hathaway; and delicate crooners like Eddie Kendricks, Frankie Beverly, and Phillip Bailey. For good measure, you’ll even find a couple of multi-instrument savants like George Duke and Quincy Jones. And charting higher than all of these, you’ll find Sylvester, who so flouted gender boundaries that she rivaled Donna Summer for the title “the Queen of Disco.”

PERUSING the Billboard Hot Soul Singles chart from the back issues of 1978, one has to be struck by the diversity that chart offers in contrast to today. The legacy of hip-hop, which was just being invented around that time, eventually eviscerated every other style of soul music such that Chris Brown, replete with tattoos and rap sheet for battery, is just about the most sensitive male artist on the current chart. (Pause and let that sink in.) But in 1978, on one chart, you could find hypermasculine lotharios like Rick James, Teddy Pendergrass, and Barry White; message men like Curtis Mayfield and Donny Hathaway; and delicate crooners like Eddie Kendricks, Frankie Beverly, and Phillip Bailey. For good measure, you’ll even find a couple of multi-instrument savants like George Duke and Quincy Jones. And charting higher than all of these, you’ll find Sylvester, who so flouted gender boundaries that she rivaled Donna Summer for the title “the Queen of Disco.”

What makes that 1978 soul chart so remarkable, even more than its improbably diverse cast, is that one man on this chart potentially embodied every description just mentioned. Because very nearly lost in that crowd was Prince, whose little-remembered first single, “Soft and Wet,” peaked at No. 12 on Billboard’s soul chart in September of that year and never cracked the pop Top 40. The single could not truly be called his breakthrough, but it opened the door to one of the most storied careers in American popular music. Prince Rogers Nelson (1958-2016) would go on to personify the testosterone-crazed lothario, the falsetto crooner, and the politically conscious singer-songwriter . He was, in fact, a one-man band who at times did everything on his albums except press the vinyl and fold the cardboard to ship it in.

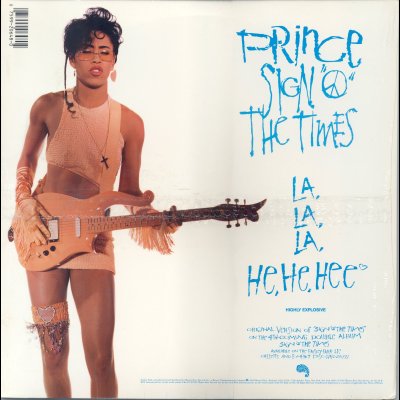

The conventional wisdom of music history is that disco was the era of sexual liberation. But no era was immune to the conservative values of the music-buying public and the industry executives who made their fortunes by catering to them. Prince made his first appearance on American Bandstand adorned with flowing hair, gold lamé stretch pants, and a large hoop earring in his right ear at a time when right-ear placement was strongly associated with gayness. Straight-male consumers at times murmured their suspicions, but his talent commanded both their respect and their buying power. In less than five years, he would have the No. 1 song, album, and film in the country, all at once.

But rather than shake the same goose for more golden eggs, he continued to change his look and sound. He made the world fall in love with his backing band, the Revolution, and then he promptly fired them all. He replaced his electric guitar with pianos and violins, and replaced his hard-rock mane first with a pompadour and then with marcelled waves. And when his record company thought there was nothing left that he could do to vex them, the man who made his living on sounds fashioned his own name into an ideogram.

To most people, it seemed that all of his antics were one long quest for greater and greater freedom, but in the last years of his life, his quest became just the opposite. The man who once routinely took to the stage dressed like a Central Park flasher became a religious conservative who redacted his own lyrics and effectively renounced all of his old sexual tactics. On April 21, 2016, this guy who had controlled every square inch of his artistic image died without a will, leaving an estimated quarter of a billion dollars to whichever probate lawyers will eventually spin the best yarn.

In a forthcoming article for The G&LR, I will attempt to sort through these many contradictions. Despite all of the things that we may never understand about him, Prince may have been the most gifted musician in the era of recorded music, and certainly also one of the most important champions of sexual freedom.

J. Ken Stuckey is a senior lecturer in English and media studies at Bentley University.