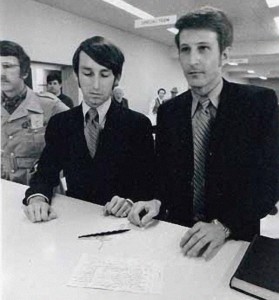

FOR THE PAST TEN YEARS, same-sex marriage has dominated the American political landscape, but this is not the first time in history this issue has made front-page news. In 1971, The San Francisco Chronicle declared that a “gay marriage boom” was under way. In the first few years of that decade, The New York Times, Life magazine, Jet, and other periodicals ran feature articles about a handful of couples who launched America’s first battles for legal recognition of same-sex marriage. Jack Baker and Michael McConnell, the best known of these couples, were invited to appear on Phil Donahue’s enormously popular daytime television show, and a number of lesbian couples quickly followed in their footsteps.

Although ultimately unsuccessful, Baker and McConnell’s campaign garnered considerable media support and gave a very fetching face to American male homosexuality. Baker and McConnell are still together today, living proof, one might say, of the power of same-sex love and commitment, and a testament to the legitimacy of the claim to marriage equality.

Baker and McConnell were no traditionalists, however. In the early 1970s, reports of increasing marital discord and rising divorce rates accompanied by the growing trend toward premarital sex and common-law living arrangements signaled an end to traditional marriage. “In the United States we are at a crisis,” Baker said in one of his many university campus speeches. “We have to change … the institution of marriage as we know it today. [We must] de-emphasize the nuclear family [and]create alternatives to marriage.” Legalizing same-sex marriage “would have such a devastating shock on … the United States that people will begin to think rationally about alternatives to the nuclear family and will begin to think of new ways to enhance the reproductive process of society.” Thus the push for gay marriage had nothing to do with reinforcing society’s traditionalist, patriarchal moorings, but was all about throwing a monkey wrench into the family system. Marriage needed to be updated. Among other things, it was time to eliminate monogamy and the legal expectation of a life-long commitment.