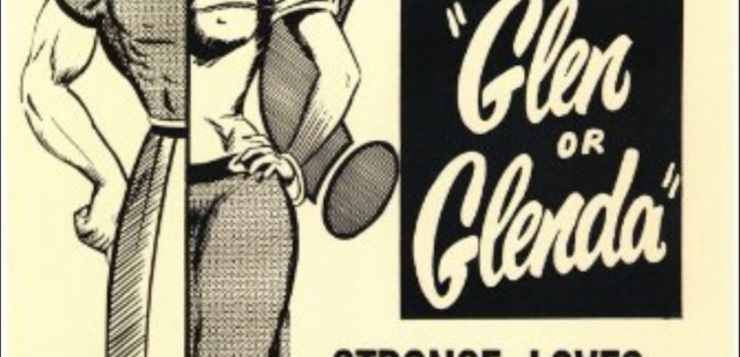

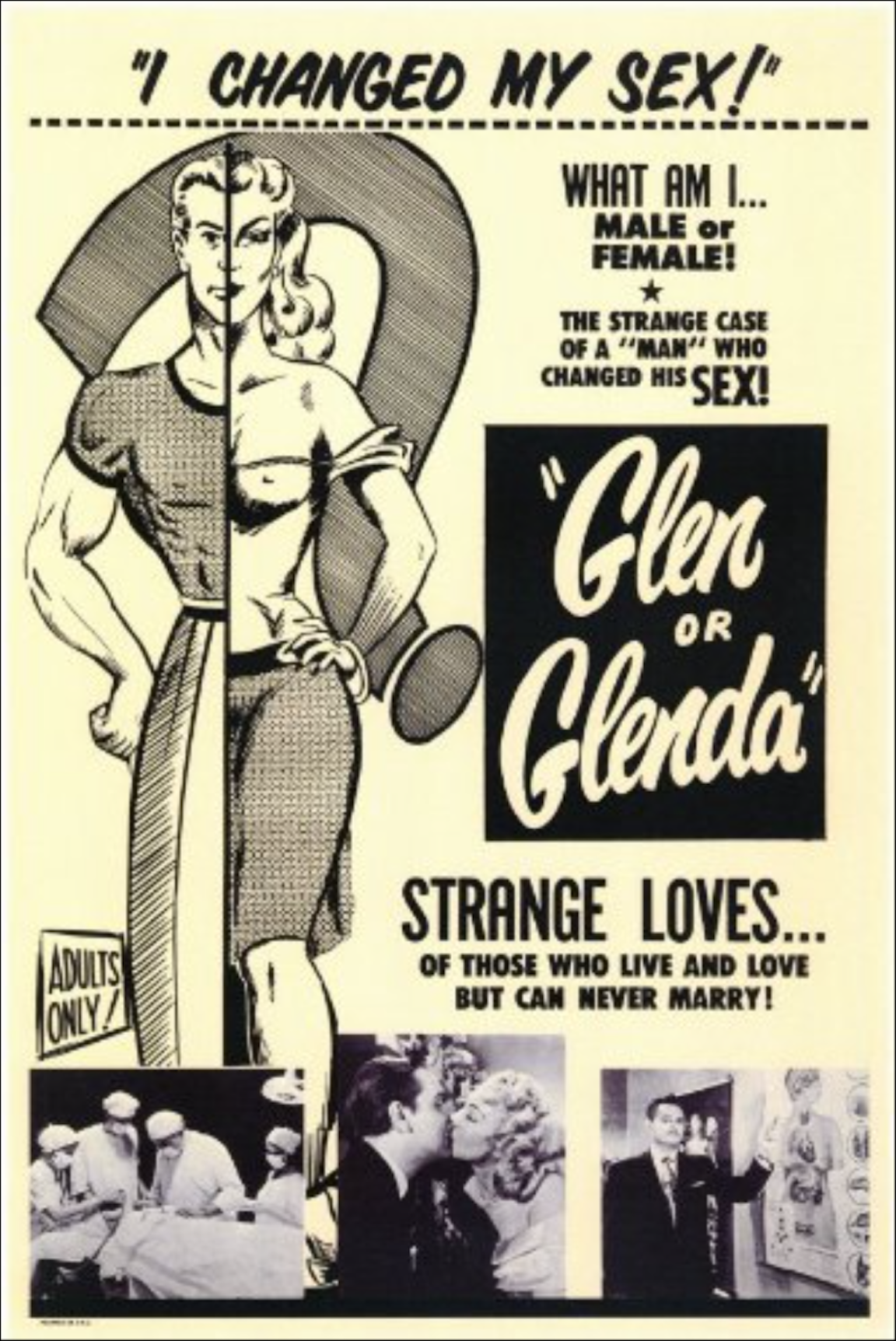

IN THIS TURBULENT PERIOD of serious nonbinary gender discussion and trans rights, the Ed Wood film Glen or Glenda seems a worthwhile artifact to re-explore. Released in 1953, it was resurrected as a camp classic in the 1980s. Panned when it was released (and included on some “worst films of all time” lists), it recalls a time when baby boys were swathed in blue, girls in pink, never to be mixed or crossed.

Glen or Glenda, originally titled I Changed My Sex, was created during the “glory years” of film noir (1940–1959). It adheres to many of the defining aspects of noir: its style is that of a quasi-documentary applied to city life. The urban environment expresses danger, isolation, fear, and anxiety, as did cross-dressing in the 1950s. Glen or Glenda is told through flashbacks, voice-overs, and odd camera angles. The only thing missing from classic film noir is the incessant lighting of cigarettes.

The film explores the bizarre phenomenon of sexual or gender diversity and uses some tropes of horror films. An aging Bela Lugosi appears, his comments punctuated with thunderclaps. There’s a portentous announcement at the outset assuring the audience that everything they’re about to see is authentic. The film then elaborates, with all the gravity of a college thesis, the practice and pathos of male-to-female transsexuality, which it tries to explain and justify. Critics Tanfer Emin Tunc and Nichole Prescott see the film as an attempt to normalize transvestism as a “guilt-free expression of male heterosexuality” (in Bright Lights Film Journal, 2015), adding that the film has been “marginalized by both audiences and critics, perhaps because it raises so many questions about the categorization of sexuality and gender within American society.” At the same time, the film ends up essentially throwing homosexuals under the bus.

The film explores the bizarre phenomenon of sexual or gender diversity and uses some tropes of horror films. An aging Bela Lugosi appears, his comments punctuated with thunderclaps. There’s a portentous announcement at the outset assuring the audience that everything they’re about to see is authentic. The film then elaborates, with all the gravity of a college thesis, the practice and pathos of male-to-female transsexuality, which it tries to explain and justify. Critics Tanfer Emin Tunc and Nichole Prescott see the film as an attempt to normalize transvestism as a “guilt-free expression of male heterosexuality” (in Bright Lights Film Journal, 2015), adding that the film has been “marginalized by both audiences and critics, perhaps because it raises so many questions about the categorization of sexuality and gender within American society.” At the same time, the film ends up essentially throwing homosexuals under the bus.

Using the trope of the mad scientist, the film opens with Bela Lugosi mixing chemicals in a laboratory, stating: “Life is begun.” This seems to be a reference to Frankenstein, the implication being that Lugosi is giving life to a “monster.” Police Inspector Warren visits psychiatrist Dr. Alton at his office to inquire about transvestite Patrick/Patricia, who’s labeled by the detective as a “four-time loser” because he’s been arrested four times for dressing as a woman. Patrick, we are told, could not afford a sex-change operation and killed herself dressed as Patricia. Her voice-over says shyly: “May I wear in death what I could not in life?” Detective Warren wants to exercise an “ounce of prevention” and try to understand the psyche of Patrick/Patricia. He sensitively wants no more such suicides.

As a product of its time, albeit an anomaly for the 1950s, Glen or Glenda tends to conflate transvestism and transsexuality. While it is indeed semi-autobiographical—Ed Wood liked women’s clothing (most notably his sister’s angora sweater)—the project was actually an assignment he received from producer George Weiss. Producer Weiss wished to capitalize on Christine Jorgensen’s very public sex-change surgery in 1952. (The front page of New York’s Daily News had blared: “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Bombshell.”) During a time of limited resistance to the prevailing conservatism and conformity of the age, Wood’s film is a hybrid sexploitation and resistance film.

Director Ed Wood was respectfully challenging the status quo while simultaneously exploiting the public’s prurient curiosity about sex, presenting a seemingly logical argument for why men should be allowed to wear women’s clothing during leisure time. He builds his argument by citing “experts” like Dr. Alton and Detective Warren. Another layer of storytelling emerges as Dr. Alton tells Warren the story of Glen/Glenda, a fully heterosexual male who is deeply troubled by his love of women’s clothing. Ed Wood uses the curious logic that, since men designed all of women’s clothing, hairstyles, perfume, jewelry, and so on, it stands to reason that they will be attracted to such articles. He even goes so far as to suggest that it is patriotic to wear women’s clothes: “Give this man satin undies, a dress, a sweater and a skirt, or even the lounging outfit he has on, and he’s the happiest individual in the world. He can work better, and be more of a credit to his community and government because he is happy.”

The pathos in this film is the normalcy of Glen in his manly suit and his devotion to his fiancée. We see and feel his shame as bits of his cover are blown, as when his girlfriend says his nails are longer than hers and the saleslady squirms as he spends too long fingering a silky negligee.

Bela Lugosi, long past his prime as Dracula, creepily chants the mantra “snips and snails and puppy dog tails.” This children’s nursery rhyme, which is documented as far back as the early 19th-century Roud Folk Song Index, injects Freudian hints of danger. It is implied that the danger lies with lurking homosexual predators. Lugosi growls: “Beware! Beware of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep! He eats little boys, puppy dog tails, and big, fat snails! Take care! Beware!” Who is the big, green monster? Is it the homosexual who is denied multiple times in this story? Ed Wood goes to great pains to make same-sex attraction look seedy in the film, including a visit from the devil himself. We are assured that Glen hasn’t a trace of same-sex attraction in his psyche. Dr. Alton assures Detective Warren that a “true” transvestite almost never has homosexual tendencies.

Director Wood delivers a final message in this quasi-documentary through the inclusion of a medical consultant, a Dr. Nathan Bailey, in the final credits. There can be no doubt that the word of the medical-industrial complex is profoundly important part of the ethos of Glen or Glenda: the rationale for this inquiry—all in the interest of science!—and the source of its credibility.

Judith R. Phagan is the chair of the English Department at St. Joseph’sCollege on Long Island.