The Homoerotics of Orientalism

The Homoerotics of Orientalism

by Joseph Allen Boone

Columbia University Press

520 pages, $50.

ONCE EVERY DECADE or so, a book appears that revolutionizes the field of GLBT studies. For many critics, Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality may have been that title in the 1970s. John Boswell’s Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality is surely the 1980s title. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble can lay claim to this achievement in the 1990s. In the intervening decades, however, there has been a sense of critics treading water—or at best extending rather than reassessing the tenets of structuralist and post-structuralist thinkers into marginally new contexts.

Across the same period, GLBT studies, while ongoing, have suffered perhaps from no longer being the new kid on the block. While the sub-discipline embedded itself in university departments starting in the ’90s, and sexuality theorists dutifully took their place on many sophomore syllabi, the publishing world was more fickle: academic presses soon found new areas of niche interest, such as animal studies, while mainstream publishing almost entirely forgot that it had once been interested in gay and lesbian ideas (with rare exceptions, such as 2008’s The Greeks and Greek Love, by James Davidson).

Now, Columbia University Press has transformed this narrative with a singular publication. For Joseph Allen Boone’s The Homoerotics of Orientalism is a book that upends current postcolonial thinking by presenting a massive, inchoate body of texts—literary and otherwise—mutually informing, supporting, and cross-referencing one another across the famously impervious East-West divide. (“East-West” here denotes relations between Western and Islamic cultures, following the formulation of Edward Said’s groundbreaking if flawed 1978 study, Orientalism.) By showing the ubiquity of male same-sex desires, cadences, and expressions within East-West discourses, Boone challenges the social constructionist dogma of feminists and queer theorists, who insist that such desires, cadences, and expressions are particular to a given cultural nexus.

Boone finally makes sense of the flow of writings, paintings, films, and other forms of art between the Islamic East and the Christian West, and what emerges is something far more credible than Edward Said’s original thesis, which was, to summarize, that Western travelers dabbled in the East, objectified it, “sold” it back to a Western clientele, and denied the subjectivity of the ethnic, religious, and cultural “other.” Said’s Orientalism set out to expose and document a persistent Western tendency both to romanticize and to patronize Arab and Middle Eastern culture. But Boone lays to rest utterly the notion that a straightforward, dogmatic, and monolithic power relationship was always being played out when Western writers and artists headed to the Near (or Middle) East.

A degree of revisionism had already penetrated postcolonial thinking. For example, Robert Irwin’s For Lust of Knowing: The Orientalists and Their Enemies (2007) argued that Said’s reading of those who first investigated Islamic societies and cultures was simply wrong: where Said saw imperialism and aggression, Irwin documents empathy and understanding. The most persuasive of Irwin’s arguments is one that Boone takes forward here: that many Westerners found themselves in North Africa or the Middle East precisely because they sought an escape from Western values, mores, and protocols and were actually predisposed to interpret what they discovered generously. Boone follows Irwin in challenging what he terms Said’s “Manichean view of West versus East” as well as his “overreliance on Foucauldian conceptions of knowledge and power that assume in advance what needs to be proved.”

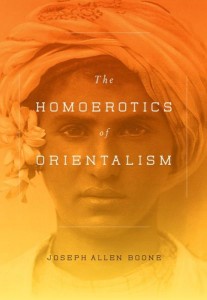

Boone’s book opens with a reproduction of a 1980 cartoon that shows Uncle Sam getting “screwed at the pump” by an Arab sheik. Many and varied have been recent deployments of sexuality in political discourse—including Greek soccer fans’ baseless accusation that Turkey’s founder Ataturk was homosexual, and the Turkish response that the ancient Greeks embraced pederasty. The surprising and refreshing use of contrapuntal sources proves to be a winning virtue of Boone’s methodical but very broad embrace of material.

We are soon reading about two entirely independent but strikingly analogous 17th-century literary sources. Boone introduces an unpromising-sounding English pamphlet from 1676—The True Narrative of a Wonderful Accident, Which Occur’d Upon the Execution of a Christian Slave at Aleppo in Turkey, a propagandistic hearsay account of a handsome eighteen-year-old French captive who refuses to succumb to the vice of sodomy. The entire narrative, Boone explains, appears informed by, if not lifted from, accounts of the martyrdom of boy-stunner St. Pelagius, who likewise resisted the sodomitic advances of Cordoban caliph Abd al-Rahman III with the words: “Do you think me like one of yours—an effeminate?” Before his execution, Pelagius is compelled to throw off the fine royal costume in which the caliph has clad him, paradoxically both insisting on his Christian resolution not to be “tied up” either in Eastern garb or Eastern vices and displaying the fine body of a “strong athlete” (though only thirteen), thus explaining, perversely, the logic of the caliph’s entreaty.

Many of Boone’s most important discoveries are in the Eastern-authored texts to which he compares a Western one. The seventh tale of Ottoman poet Nev’izade ’Atayi’s Heft Han (1627) tells a story so unlikely and unforgettable as to require extensive summary.

Two Istanbul merchants sire two fine sons, Tayyib (“beautiful”) and Tahir (“pure”), who grow up as inseparable friends. On the death of their fathers, they run amok with teenage hormones, dissipating their inheritances in the all-male wine bars of Galata. Broke and abandoned by their drinking companions, the pair sets sail to Egypt to join an order of Sufi dervishes. Following a shipwreck, they’re both plucked from the Mediterranean by an “infidel” (Christian) warship and taken prisoner. When they reach shore, however, Tayyib and Tahir are adopted as slaves by two respectable “heart-stopping beauties”—Christian noblemen from the ship—Sir John and Janno. Both boys fall in love with their captors, and when Tayyib tells Sir John that his happiness will be complete when he is reunited with his childhood friend, Tahir and Janno drop in at Sir John’s estate and a set-piece sohbet ensues: a luxurious garden party where noblemen and beautiful boys chat, recite verse, flirt, and drink wine.

A busybody reports the sensual goings-on to a puritanical policeman, who imprisons the noblemen and prepares to behead their boy lovers as an example to all. However, a crowd of Christian onlookers objects: “If we start killing prisoners this way, What’s to keep Muslim swords from coming into play? If captives on both sides are caused to die, Who on Judgment Day will answer why?” The policeman commutes the boys’ sentence to enslavement on a galley ship, and they once again set sail. In a bizarre development, they are released by their fellow Muslim prisoners and come to govern the ship: “The pirates of love become the captains of the sea.” Meanwhile, Sir John and Janno have struck up conversation with Muslim prisoners in jail, convert to Islam, and find the Prophet miraculously releasing them from their chains. They set to sea in a rowboat and are discovered by Tayyib and Tahir: the four “met friends instead of foes … each met his lover, became friends with each other’s lover.”

The final obstacle to a benevolent resolution—the difference in religion—is now overcome, and both couples retire happily to Istanbul. Sir John is renamed Mahmud (“praiseworthy”) and Janno Mes’ud (“fortunate”). Both couples pass with “pure love” from the worldly paradise they inhabit to the “holy garden” of the next. Their story assumes the status of a “magical legend.” As well as being tailor-made for a musical adaptation to melt the heart of even the most secular gay man, this story is arrestingly bizarre at every turn, inverting our expectations and also making us wonder, who precisely is the imagined reader of such a text? And how, at a time when sodomy and homosexuality so routinely inform muscular Christian narratives affirming purity through denial and renunciation, does this Eastern text so confidently embrace gay desires and intergenerational relationships, magically resolving its romantic themes with one of the world’s first happy gay endings?

Boone did not discover this remarkable narrative poem and duly credits a remarkable source that brought it to light, along with a wealth of colonialist works suggesting substantial overlap and convergence in themes, namely The Age of Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early-Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society (2005), by Walter Andrews and Mehmet Kalpakli. After analyzing this and other works, Boone concludes: “the linkages and disconnections between so-called ‘West’ and ‘East’ over the terrain of male homoerotic desire reveal, in examples such as these, a complexly imbricated history whose representations and actualities cannot be reduced to the oppositions the popular imagination often summons forth when using charges of homosexuality to categorize and castigate the other.”

Boone goes on to describe a strain of envy and self-contradiction found in many European travel accounts of the Ottoman court’s supposed dissipation and moral turpitude. In some descriptions, awkward contrasts are insisted upon between the unwholesome love of pubescent boys in the East and the “honorable” affection for Ganymedes in ancient Greece. Essentially, many Western travelers—themselves often particularly concerned not to be identified with the vice they observed—got caught up in seeming to advocate the very temptations of which they were reporting the dangers.

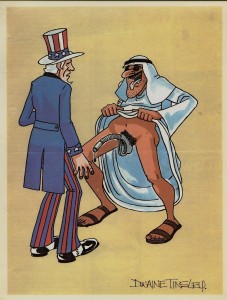

Perhaps the most pronounced example of this double standard is a painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Snakecharmer, which was featured on the front cover of Said’s opus because it so neatly summarized his assault on Western values. The painting suggestively places a line of leering, recumbent Ottoman men before a pre-pubescent boy who holds aloft a snake, which undoubtedly represents his own unseen male member. At the same time, however, the viewer (presumably European) is implicated in admiring the boy’s rear end, which is seen by the viewer but concealed from the crowd of men. Do we then share in a circle of culpable admirers here, or stand aloof from these Eastern “others”? How can we prove our own distance, as we regard the boy from the only vantage point we have? Gérôme not only proves himself aware of the contradictions in Orientalist art—including the very market-oriented parades of sensuality that this canvas embodies—but also traps the viewer within them.

There are many other contexts in which Boone can only begin to lay out ways for the next generation of scholars to further complicate East-West cultural dialogue and highlight the hazards of mutual misunderstanding. Many of the writers we expect to find do appear—Pierre Loti, André Gide, Lawrence Durrell, Naguib Mahfouz—alongside less expected figures, such as Norman Mailer and the forgotten Brit Robin Maugham. What also resonates is Boone’s determination to push his arguments not only into the present day but also into all genres of art. There are smart readings here of Italo-Turkish filmmaker Ferzan Ozpetek’s Hamam (2000) and Egyptian cineaste’s Youssef Chahine’s gender-bending 1970s Alexandrian trilogy, plus a fully convincing if less surprising reconsideration of Pasolini’s Arabian Nights (1974).

This is a book that post-colonialists will seize immediately and argue over endlessly—but one that will also permeate the wider GLBT intellectual landscape, in the best ways and for the best reasons. Every reader will benefit from its radical and unsettling rethinking of East-West cultural exchange. And, as The Homoerotics of Orientalism keenly points out, there has scarcely ever been a better time for such rethinking to begin.

Richard Canning’s most recent publication is an edition of Ronald Firbank’s Vainglory for Penguin Classics (2012).