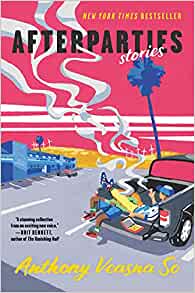

AFTERPARTIES: Stories

AFTERPARTIES: Stories

by Anthony Veasna So

Ecco. 272 pages, $27.99

AUTHOR Anthony Veasna So died of a drug overdose on December 8, 2020. His first book, the short story collection Afterparties, was published on August 3, 2021, and was named one of the top 100 Notable Books of 2021 by The New York Times—almost a year after his death. So died before he could see the rave reviews for his collection, before it was selected for Roxane Gay’s book club, and even before the edits were finalized. In many ways, the book has come unmoored from the author, the machinery of its publication, promotion, and reception stewarded not by So himself but by those he left behind: his partner, publisher, agent, editor, and family members.

In a moving profile of So written by E. Alex Jung for the arts and culture magazine Vulture, this machinery is described as being set in motion by So to build a career, but in his absence it has continued to operate and essentially to rewrite his story. Jung notes that “[So’s] death has ascribed a different myth to him”—not the rising star who walked into n + 1 magazine offices and charmed the editor into publishing one of his stories, but the dead rising star being lionized by an industry that barely got to know him. So’s legacy and work will be forever out of his control. (His second book, tentatively titled “Songs on Endless Repeat,” will include chapters from the novel he never finished, Straight Thru Cambotown, along with a selection of his essays.)

As the only book completed by So, Afterparties stands as one of the few parts of his legacy that he did control. In these pages, we encounter the clearest version of his voice as a writer, including all the contexts from which that voice arises. So was queer and bipolar. He was a Cambodian-American from a large, conservative family, in which he appears to have been the only artist (his cousins are lawyers, tech workers, deans of students). He graduated from Stanford and later earned his MFA at Syracuse. His short stories mine the many intersections of his identity.

In the first half of the book, So establishes a voice, a common lexicon from which all of his characters draw in their self-descriptions and self-deceptions. In “The Shop,” a son believes that he lives at home to help his family out with the shop when in reality it’s the reverse: his father is keeping the shop open so his son will have time to figure out his life. After this story, the book takes an important vocal turn, opening up to new experiences and contexts. In “The Monks,” the protagonist retreats from day-to-day life after his father’s death to live at the wat (a Buddhist temple), where he makes lists as an exercise in understanding his situation. In “Human Development,” the main character, one of the few queer Cambodian-American men in the book, hooks up with another Cambodian man via an app, only to be disappointed. In “Somaly Serey, Serey Somaly,” the female narrator works as a nurse at an assisted living facility, where she cares for the elderly Ma Eng, who mistakes her for a dead family member. In the final story, “Generational Differences,” a mother tells her life story to her son, recounting her experiences leading up to a shooting at his school. Near the end, she asks: “What is nuance in the face of all that we’ve experienced?”

For So, a remarkably nuanced writer, that is indeed an important question. It stands both as a reminder of the grief lurking underneath all the stories and of the many ways that the stories can be told. This, I think, is the source of the mythmaking and lionizing being done in the wake of So’s death. He could tell so many kinds of stories, and he knew it. ____________________________________________________