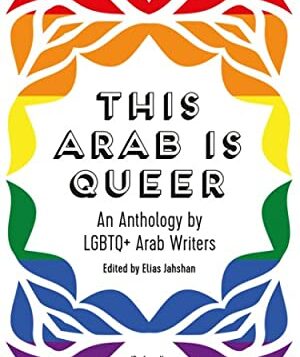

THIS ARAB IS QUEER:

THIS ARAB IS QUEER:

An Anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab Writers

Edited by Elias Jahshan

Saqi Books. 288 pages, $19.95

Elias Jahshan’s mission in This Arab Is Queer is clear: he seeks to provide a platform for LGBT Arabs to speak for themselves. Asserting that Western coverage of queer Arab lives often focuses on sensationalist news stories that “rarely engage with Arab voices directly,” he has collected narratives from eighteen Arab writers from eleven countries and the diaspora to present a fuller, more accurate depiction of queer Arab life.

Jahshan gave the contributors free rein, encouraging them to share any subject matter of their choosing. Many writers studiously avoided “the trauma narrative” that has marked much Western understanding of queer life in the Arab world, which is based on the assumption that LGBT Arabs’ lives are relentlessly oppressed and driven to secrecy. These ideas are confronted directly in several essays, including Lebanese-Australian writer Tania Safi’s “Dating White People,” in which, after describing several problematic relationships with white women, she explains: “I wasn’t aware of the concept of racialized fetishization, but I knew how it felt.” A similar theme is struck in Emirati writer Saeed Kayyani’s “Trophy Hunters, White Saviors and Grindr,” which recounts a number of disturbing incidents with Western men and women, including a male lover’s declaration that Kayyani should thank the lover for having sex with him: “You know for a fact that you’d get killed in your country for this shit. I’m doing you a favor, man.”

Of course, writers recognize the punitive legal system and repressive measures that dominate the culture of many Arab countries, yet nuanced consideration of individual queer settings and circumstances often yields narratives of insight and possibility. British-Iraqi performer Amrou Al-Kadhi, in “You Made Me Your Monster,” traces his struggle with the Koranic stipulations that homosexuality is a sin and that parents go to hell if their children do. He then chronicles his embrace of drag, a transgressive gesture that at its best “builds bridges and understanding.” A similarly positive note is sounded by bookstore owner Madian Al Jazerah, a Palestinian Kuwaiti living in Jordan. In “Then Came Hope” he explains that, while he can’t celebrate his book publication in his store in Jordan, he is able to launch the book in Cyprus, where members of the activist group Queer Cyprus, all in their twenties, ask questions, mingle, and celebrate.

Jordan is also the setting of one of the most inspiring pieces in the collection, Khalid Abdel-Hadi’s “My Kali—Digitizing a Queer Arab Future.” Abdel-Hadi begins by recalling the personal attacks and public outing that greeted the appearance of his digital magazine My Kali. He describes the journalistic condemnation and the roadblocks that were erected to stop the publication. His indictment of Jordanian media is fierce, but he insists that its destructiveness only spurred him on in his struggle to keep publishing. By the end of his piece, he can proudly report that My Kali is still publishing after fourteen years. While censored in the Gaza Strip, Jordan, and Qatar, its bilingual English-Arabic edition on the experiences of queer Arabs regularly reaches 22,000 readers and boasts 76,000 followers across its platforms. The publication also hosts digital events that provide safe and visible spaces for queer artists. In this way, Abdel-Hadi concludes: “My Kali proves that it is possible to reach beyond state-sponsored intolerance. The internet offers a world of its own and My Kali continues to encourage a borderless community.” These are encouraging words indeed.

Other essays deepen our understanding of individual lives in various ways. In the beautifully written “Unheld Conversations,” Palestinian diasporic novelist Anbara Salam describes her mother’s silence upon the publication of her second novel featuring a queer Arab female narrator. This prompts an observant meditation on the prevalence in Arab culture of “withheld conversations about queer identity.”

“An August, a September and My Mother,” written by Egyptian pseudonymous contributor Amina, strikes a poignant chord in its recollection of the aftermath of an exuberant 2017 concert in Cairo of the queer Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila. Amina remembers her feelings of pride and freedom when several rainbow flags were waved amid the crowd of 35,000 spectators. Those feelings quickly changed to fear as a homophobic backlash ensued the following day, and several flag wavers were arrested. Among them was Sarah Hegazy, a lesbian activist who suffered three months of torture in an Egyptian prison before being exiled to Canada and committing suicide at age thirty. Amina skillfully interweaves her personal story involving her inability to share with her mother moments of joy at the concert and in future love relationships. Amina ends the piece with a fantasy in which she dances with her mother at her wedding to a woman. The sad account of Sarah Hegazy’s life and death forms a powerful coda.

To be sure, like many groundbreaking anthologies, This Arab is Queer might have been edited more tightly. Sudanese-Arabian Ahmed Umar’s well-written and engaging “Pilgrimage to Love” abruptly ends, leaving several unexplained narrative threads. Several essays lack a clear thesis, and the last offering, by Lebanese-Turkish-Australian Omar Sakr, “Tweets to a Queer Arab Poet,” isn’t an essay at all but rather a compilation of 43 exhortations and observations that certainly need context.

Despite its unevenness, this anthology represents an important step toward exposing Western readers to the range of queer Arab writing. Editor Elias Jahshan’s expansive attitude toward his project as a beginning is revealed as he concludes: “I look forward to discovering the plethora of unique stories that are waiting to be told.” In this regard, he is not alone. As the landscape of queer Arab writing broadens and becomes increasingly available, Western readers have much to anticipate.

Anne Charles cohosts the cable-access show All Things LGBTQ with her partner in Vermont.