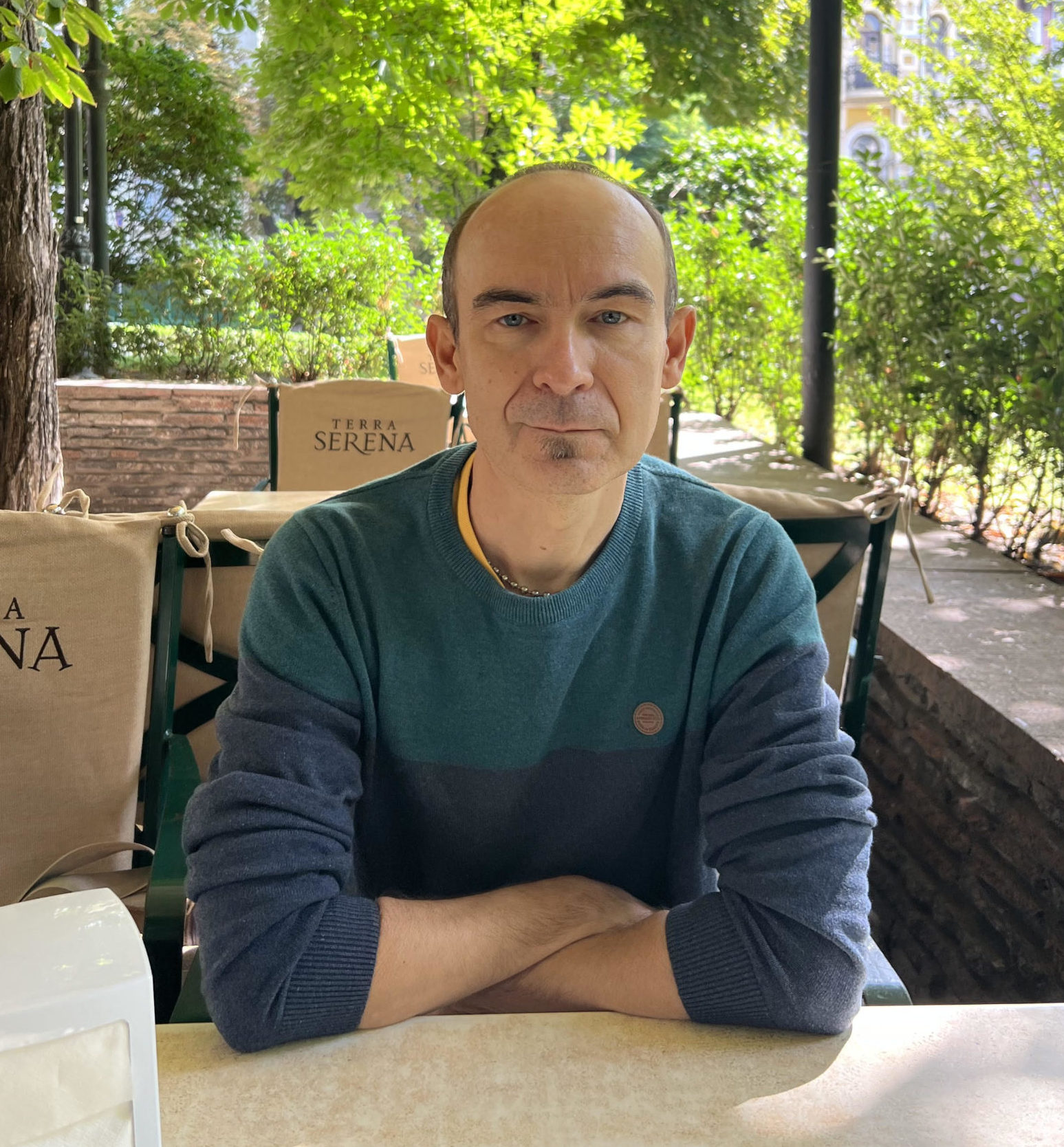

SINCE RUSSIA’S WAR of aggression began on 24 February 2022, the lives of everyday Ukrainians have fundamentally changed. Many people in Ukraine’s lgbtq community are fighting in the military to repel Russian forces and liberate their homeland. Andrii Kravchuk is a Ukrainian lgbtq activist, one of the founders of the Nash Mir (Our World) Gay and Lesbian Centre, Ukraine’s leading lgbtq advocacy center, and is currently working to support the country’s lgbtq community, which is under siege.

We met at the open-air café next to Termen’s Fountain in Kyiv and discussed the current situation for lgbtq people living in Ukraine, how the war has altered the lives of Ukrainians, and the likelihood that same-sex marriage will become a reality in Ukraine after the war ends. The interview, which was conducted in English, has been edited for length and clarity.

Finbarr Toesland: What is the Nash Mir Gay and Lesbian Centre, and how did you operate before the Russian invasion?

Andrii Kravchuk: The Nash Mir Centre is one of the oldest Ukrainian lgbtq organizations. We started 25 years ago. For a year after we began our activities, we fought with our local Department of Justice because they didn’t want to register us as an openly lgbtq organization.

When I talk about “us,” it was just some friends who started the center as a group of young gay guys. It was during the first years after Ukrainian independence, and we saw opportunities to improve society for lgbtq people. Since then, we have set up a monitoring network for anti-lgbtq violence, discrimination or other violations of rights in Ukraine.

Until 2014, we never cooperated with the Ukrainian government. They rejected all of our proposals and did not want to speak to us. After a better person became president of Ukraine, the situation changed. We are currently cooperating with our government in some areas. For instance, they invited us to work on some important policies around civil rights. Even in 2015, when the first lgbtq action plan was adopted by our government, it was absolutely unexpected for us. They included all our proposals. Not all became law, around one-third did, but it was still very good.

Before the war, we had a series of trainings with local police forces around sexual orientation and gender identity. They were quite effective and well-received in most cases, but we couldn’t manage to finish a session in Vinnitsa. Those meetings were disrupted by local anti-lgbtq organizations, and even the police could not protect themselves from this attack.

Lviv was the only city where we tried to organize such a meeting with police, but it failed, because we were of no interest to the local police. Lviv is a major center for far-right nationalism, and they see lgbtq people as enemies, not just on a political basis but also on a national basis.

FT: With the anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine coming up, could you talk about how the events of the past year have impacted lgbtq rights and the community itself?

AK: It has dramatically worsened our everyday life but definitely improved the political and legislative situation of the Ukrainian lgbtq community. I’m sure you understand all horrors of the war which we’re experiencing. However, obtaining the candidacy to the EU enabled the Ukrainian authorities to adopt two symbolically important documents protecting lgbtq rights: the ratification of the Istanbul Convention and the law “On Media.”

The war drew public attention to the problems of same-sex partners fighting for Ukraine and undermined all efforts of Russian homophobic propaganda. The public trust in the ultraconservative Ukrainian churches has decreased sharply, while the stance towards lgbtq people has improved.

The most important issues facing Ukrainian society are the global changes that are happening. We are part of a globalized world. Of course, we have open communication [unlike Russia], and therefore free access to the internet and global information. Ukrainian civil society is also quite strong. I’m proud of this, because I’ve met with many activists from Eastern Europe, and Ukrainian civil society is one of the strongest. Ukraine is one of the most progressive countries in the eastern part of Europe. Understanding the necessity of European integration for Ukraine and the global changes towards lgbtq issues has influenced this change.

FT: A number of openly lgbtq people have fought for Ukraine against Russia. Do you believe this is one reason why attitudes have improved towards lgbtq people?

AK: Definitely. Iryna Sovsun MP, the only active supporter of the lgbtq community in the Verkhovna Rada, said that some of her homophobic colleagues changed their minds towards lgbtq people when their real participation in the war became known.

FT: Could you talk about some of the main projects the Nash Mir Centre is currently working on for the community?

AK: Given the current situation, we cannot provide substantial financial assistance to the community, so we have focused our activities on the advocacy of political and legislative change. This year, the Ukrainian parliament is to discuss two bills of crucial importance: one on the criminalization of hate crimes, including on lgbtq grounds, and the other on making civil-registered partnerships available for same-sex couples.

Last May, my organization completed a survey on attitudes towards lgbtq people in Ukraine. We repeated the questions we asked about six years ago, and it showed that current attitudes of lgbtq issues have improved radically.

FT: When the war of aggression is over, do you think that lgbtq people will gain equal rights in areas such as same-sex marriage?

AK: Beyond any doubt, it will eventually happen in the mid-term prospects. The task to adopt a law on civil registered partnership has been already included in action plans of the Ukrainian government, and the recent decision of the ECHR [European Court of Human Rights] in the case Fedotova and Others v. Russia left no place to evade this for the Ukrainian authorities. The question is not whether, but how soon, same-sex couples will be allowed to marry, and the trends are only becoming more favorable.

This war attracted public attention to the problem around same-sex marriage, because many lgbtq people are serving in the Ukrainian army, and they have absolutely no protection. It’s quite understandable, for the general public, that you should protect the rights of your defenders. We try to use these possibilities to work for the adoption of same-sex marriage—it’s one of the most important tasks. So we are working with our Minister of Internal Affairs on this.

Finbarr Toesland is a UK-based freelance journalist who has written for The Times, The Telegraph, BBC, Reuters, and other outlets.