IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY, Making It, arch-homophobe Norman Podhoretz describes the sense of urgency that surrounded the appearance of a new novel in the 1950s, which he attributed to the “tyranny of taste” that thrives in “politically quiescent periods,” when readers are desperate to be told by political authorities what to believe and by cultural authorities what to enjoy.

This formulation is of no help, however, when one tries to explain the fervor with which gay readers greeted the publication of James Purdy’s Malcolm in 1959. A friend once described to me how, on Fire Island that summer, rows of men bronzed on the beach as they read the novel, forgetting even to cruise the passers-by, in order to be prepared for the discussion that would invariably dominate conversation at that evening’s social gatherings. “Night after night, we argued at dinner [over]what each character represented and what the bizarre actions meant,” my friend recalled. “For Halloween that year, people dressed as Malcolm, Kermit, Cora Naldi, and Estel Blanc. One group even came to a party as Madame Girard and her ten identical young men.”

Malcolm is the story of an inexperienced fourteen- or fifteen-year-old boy who sits daily on a golden bench outside a luxurious hotel, waiting for his father, who seems to have forgotten about him. (Malcolm learns his age only after he opens his mouth for a curious mortician who examines the boy’s molars.) Malcolm’s education is taken in hand by Dr. Cox, a preening astrologer, who lures the boy off his bench and encourages him to forget about his father and instead call on a number of addresses of people who can introduce him to the larger world. Malcolm’s new contacts include the most outré denizens of both high and low society, including: a socially self-conscious “Abyssinian” mortician; a midget artist and his prostitute-cum-stenographer wife; an imperious society matron and her fabulously wealthy husband; a nearsighted female portrait painter with a fondness for black jazz musicians; a motorcycle rider who’s the leader of a set that styles itself “the contemporaries”; a doting tattoo artist; the madam of a Mexican bordello; and the sexually voracious, drug-addicted rhythm-and-blues singer whom Malcolm, not yet sixteen, marries shortly before his death. The novel’s refusal to specify the setting or the year leaves these eccentric characters unmoored in time and place.

On the surface, the novel appears to be—like Voltaire’s Candide, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or Dickens’ David Copperfield—a bildungsroman: a narrative of a young man’s coming of age. But while his interlocutors are easily charmed by Malcolm’s “youth and freshness,” they are just as likely to be exasperated by his naïveté, and they privately question his intelligence. “Give yourself to things—to life!” Dr. Cox exhorts him when Malcolm asks the older man what he should do after being abandoned by his father and finding that his money will soon run out. Malcolm’s “openness, benign acceptance of everything, and puzzling expectancy”—what Dr. Cox calls his “waiting look”—endear him quickly to everyone he encounters. And all are eager to help him get his start in life.

On the surface, the novel appears to be—like Voltaire’s Candide, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or Dickens’ David Copperfield—a bildungsroman: a narrative of a young man’s coming of age. But while his interlocutors are easily charmed by Malcolm’s “youth and freshness,” they are just as likely to be exasperated by his naïveté, and they privately question his intelligence. “Give yourself to things—to life!” Dr. Cox exhorts him when Malcolm asks the older man what he should do after being abandoned by his father and finding that his money will soon run out. Malcolm’s “openness, benign acceptance of everything, and puzzling expectancy”—what Dr. Cox calls his “waiting look”—endear him quickly to everyone he encounters. And all are eager to help him get his start in life.

But percolating beneath the surface of the narrative is an undertone of sexual ambiguity that makes Malcolm anything but a traditional coming-of-age story. These hints of sexual irregularity are what must have proven so enticing to readers in 1959. For example, although Dr. Cox never propositions Malcolm, the boy is repeatedly warned by others that the astrologer is “an old pederast,” a word that Malcolm does not understand and fails to look up in the dictionary despite his professed intention to do so. Purdy would never be so vulgar as to label Madame Gerard a “fag hag,” but it’s true that the doyenne surrounds herself with attractive young men who delight in her chic furnishings and boldly stated opinions. Madame Gerard fondly refers to Malcolm and Kermit as “my immature ephebes,” “my young beauties,” and “my handsomes.” And much to Malcolm’s discomfort when he first visits Kermit, he finds the beautifully formed midget being served breakfast by a half-naked “morning servant” (as opposed to Kermit’s afternoon and evening servants), who in a certain light seems to be wearing nothing at all.

Even more opaque are the goings-on in the household of Eloisa and Jerome Brace. The painter and her charming ex-convict husband keep open house for black jazz musicians passing through the city. Both Eloisa and Jerome seem to have once been lovers with both Mr. and Mme. Gerard (for a total of six dyads), and they exchange wet kisses and long-held recriminations with the latter couple when the four meet to discuss Malcolm’s future. Jerome actually appears to be on the verge of accomplishing his seduction of a tipsy Malcolm, when the scene suddenly fades to black, only for Malcolm to awaken, not in bed with Jerome (as the reader might have expected), but with a jazz pianist. Malcolm spends the remainder of his stay in the populous Brace household sleeping “with a different person each night, and sometimes—where there is real crowding, Eloisa has to move him in the middle of the night to a different bed. Often it’s more apt to be three in a bed than two.” Little wonder that when asked by Gus if he is a virgin, Malcolm has difficulty determining his sexual status. “I’m a little bit of this and that / But I’m all one solid,” sings Malcolm’s eventual wife, the popular rhythm and blues performer Melba, on the night they first met.

Malcolm came out at a time when television husbands and wives slept in twin beds, Doris Day and Rock Hudson exchanged only chaste kisses, and Annette Funicello’s bikini and Frankie Avalon’s swimming trunks were constructed to cover the wearer’s navel. Gay readers must have been dazzled by the ongoing debate in Malcolm over the trials and tribulations of heterosexual marriage, and left to gasp at how much Purdy was able to insinuate about sexual unorthodoxy without explicitly stating anything. “Texture is all, substance nothing,” Madame Gerard explains as she dons a “bluish purple” riding veil before entering a public park late one afternoon. Motives—especially sexual motives—are never clear in Malcolm (for example, why Madam Gerard suddenly insists that they stop the car to visit the park), but details supplying texture (the unusual color of her riding veil) may strike a vibrant chord in the reader’s imagination. As in the novels of Ronald Firbank, the texture of the world is so powerfully rendered that the reader easily accepts the seeming lack of substance.

Yet Purdy’s greatest accomplishment in Malcolm is to create a world in which people are not simply playing a set of social roles but have no identity apart from these roles—a world, in short, in which texture or style is the only substance. When pressed by her husband for a divorce, Madame Gerard’s only objection is: “But my name! I am known everywhere as Madame Gerard.” She alleges that her husband, in taking his name away from her, intends in effect “to destroy my identity.” When the reader meets her again after the divorce, she is still identified as Madame Gerard, apparently because she is unable to step out of this role. Elsewhere, Madame Gerard compliments Dr. Cox for being “firmly evasive.” As an astrologer who tries to control the lives of everyone around him, his authority depends upon his never making so explicit a prediction that he will be revealed to be a charlatan when it fails to come true. Thus his role is to be as firm or as authoritative in his evasions as possible, and Madame Gerard applauds him for successfully playing his part.

Everything in Purdy’s Malcolm may be described as “firmly evasive,” which no doubt enhanced the sexual mysteriousness of the novel for its original readers. Early in the novel, unable to follow Malcolm’s explanation of his relationship with Dr. Cox, Estel replies “Of course” by way of encouraging Malcolm to continue, only to reflect suddenly “that he had said of course to something he had not understood in the least.” Estel’s acceptance of an explanation that makes no sense to him models the reader’s best response to Purdy’s novel: we benignly accept its absurdity simply because it is so vibrantly rendered. The strychnine that infuses Purdy’s whimsy only emerges, however, once the reader accepts the texture of his characters. For it is then that Purdy removes the blue-violet veil and exposes the substance that the reader had been seduced into thinking does not exist. Purdy’s tone changes dramatically in the last quarter of the novel as Gus, the black motorcyclist who is instructed by Melba to “mature him [Malcolm] up just a little,” takes the boy to a tattoo parlor and a bordello. And while Malcolm retires to a room upstairs with Madame Rosita, Gus teaches the boy the ultimate truth about maturity: the inevitability of death.

No explanation is given for the motorcyclist’s own sudden death. What’s more, the cold reality or “substance” of human mortality is delivered with the same equanimity as any other action taken or opinion expressed elsewhere in the novel. In effect, Purdy forces the reader to accept the inevitable consequences of people “act[ing]out the parts they are meant to act out with one another,” as Dr. Cox insists that the members of his coterie do. While socially naïve and in need of having the subtleties of most interpersonal relations explained to him, Malcolm remains everyone’s favorite precisely because he intuits perfectly the role that each of his interlocutors is playing and invariably comments shrewdly upon it. And while he may offend someone when his unintentionally blunt observations reveal the unattractive truth beneath the role-playing, Malcolm is—like Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin—a holy innocent who lacks the protective coloring needed to survive in society, as those around him recognize to varying degrees.

“Oh, to be wanted, adored, sought after,” Kermit jealously exclaims upon first hearing of Malcolm’s unprecedented success with the wealthy and elite Girards. Gus’s death, however, leaves Malcolm in far worse straits than those in which Dr. Cox found him after his father disappeared. “I’m not so young now anymore,” Malcolm realizes, only to see his hair turn white overnight; and then for him to die “from acute alcoholism and sexual hyperaesthesia” after just a few “weeks of incessant marriage” to the booze- and sex-addicted Melba. What other fate could have befallen Malcolm, who so successfully acted the part of the innocent in a world lacking in substance?

It is little wonder that in 1959 gay readers were obsessed with cracking what seemed to be the novel’s enticing yet ultimately unfathomable code. Ten years before Stonewall, readers were excited to find non-normative sexual experience delivered in such a casual, yet finally insubstantial, way. And because Malcolm was Purdy’s first novel to be published in the U.S. (a novella and a collection of short stories had appeared earlier in the U.K.), the author himself was an enigma to early readers: Was he gay or straight? African-American or white? As a storyteller, Purdy seemed to be the Cheshire Cat who appears in the strangest of places only to dematerialize when on the verge of answering Alice’s most vexing questions. The novel’s popularity stemmed not from Podhoretz’ “tyranny of taste” but from the exuberance with which readers took to heart its provocative ambiguities.

But in 1959 readers could not foresee that Purdy’s first novel was simply an amuse bouche to the heavier fare that he would serve up in novels like Eustache Chisholm and the Works (1967) and Narrow Rooms (1978)—novels in which Purdy stoically accepts the horrifying inevitability of men “act[ing]out the parts they are meant to act out with one another.” In fact, I doubt that anyone could have anticipated how close to the horrifying sublimity of ancient Greek tragedy Purdy’s art would reach—as close as any American writer has ever come.

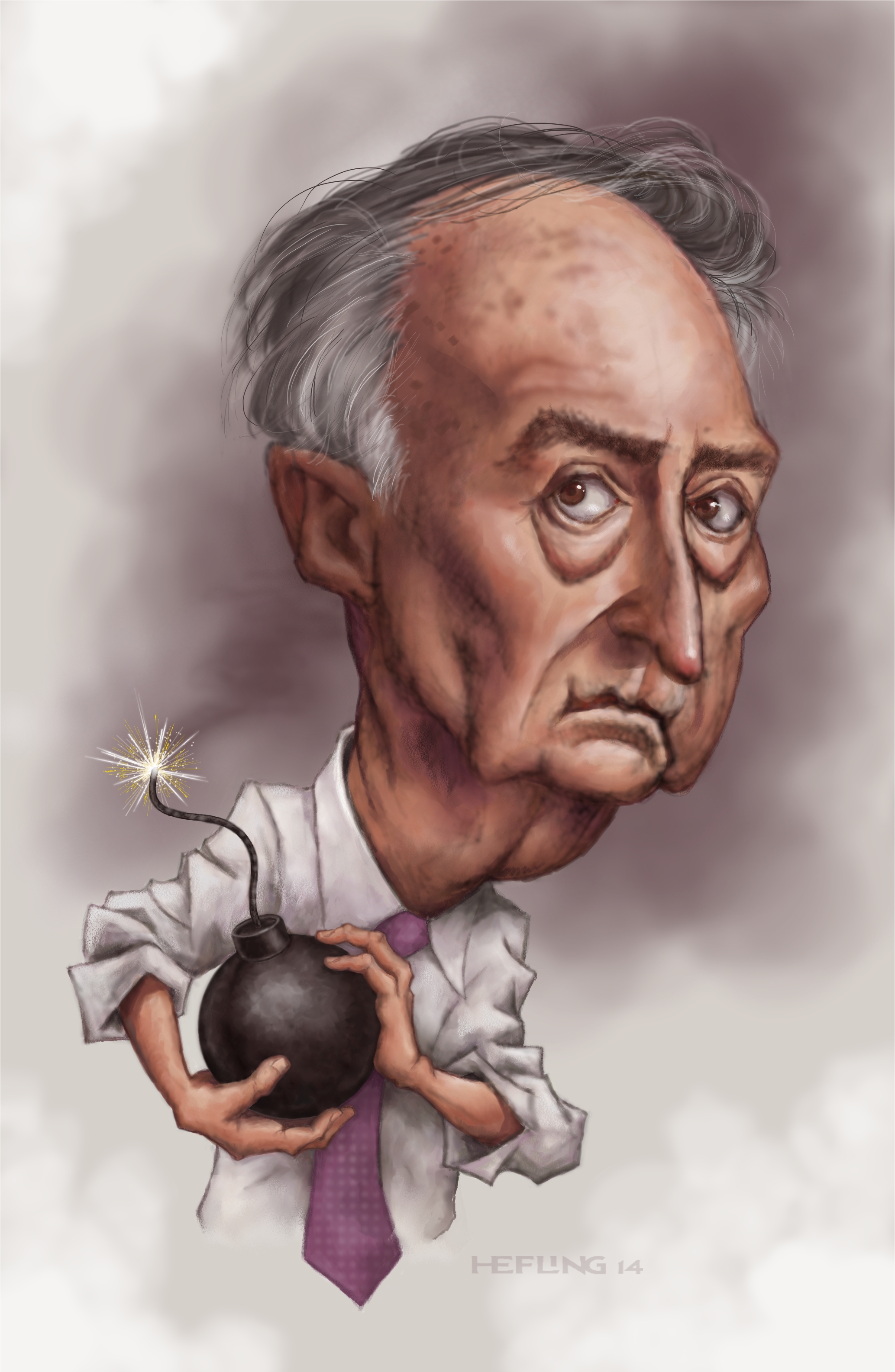

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the University of Central Arkansas.