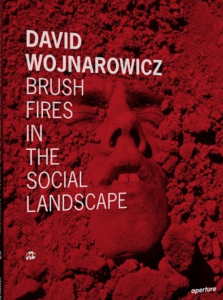

Brush Fires in the Social Landscape Second Edition

Brush Fires in the Social Landscape Second Edition

Photographs by David Wojnarowicz

Aperture. 240 pages, $55.

AS A YOUNGSTER, David Wojnarowicz navigated cattail swamps, wetlands, and the Navesink River estuary in the semi-rural setting of Red Bank, New Jersey, where nature was a life-sustaining refuge from abusive relationships and an unstable family. Twenty-four miles from the tip of Manhattan, he explored reptile and insect realms where decaying matter bred millions of insects. Cynthia Carr wrote in Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, that “he especially adored the unlovable reptile and insect realms. He always said that if he brought home some injured creature, his father would ‘take it in the yard’ and make David ‘watch him shoot it.’”

Brush Fires in the Social Landscape is a twentieth-anniversary expanded and redesigned edition of a monograph with the same title published in 1994 by Aperture #137. Wojnarowicz had been in talks with Aperture’s editors about publishing a book of his work, but he died of AIDS in July 1992 before the project was completed. The book was published posthumously. It includes essays from more than thirty contributors—critics, curators, fellow artists, and friends—who address the artist’s legacy.

The Works of Wojnarowicz

Lucy Lippard, art critic, activist, and feminist, makes a convincing case for Wojnarowicz’ centrality as a late 20th-century artist. She writes: “The same tenderness and compassion—the antidote to outrage, just as the peaceful, ordered photographs might be seen as antidotes to the furious chaos of many of the paintings—is evident in the photograph of a hand holding a frog, very gently.” Another picture shows a beetle crawling across the pond, and in a third—of a much smaller frog in the hand—there is a text that begins, “What is this little guy’s job in the world?” Tom Rauffenbart, Wojnarowicz’ long-time partner, confirms Lippard’s observations about his sensitivity, in the section titled, “Wandering—Lusts—Creatures”:

Nothing fascinated him so much as searching out and photographing live animals or insects. … On one trip to Louisiana … David hopped on shore and began turning over rocks and dead tree branches until he found a small nest of identifiable, eyeless, slimy creatures squirming underneath[;] gently he picked up one in his fingers, held it in front of his camera, snapped a few shots, and just as gently returned it unharmed. … His respect for life was so strong that he thought nothing of putting us in danger in order to avoid squashing some creature appearing out of nowhere in front of us when we drove.

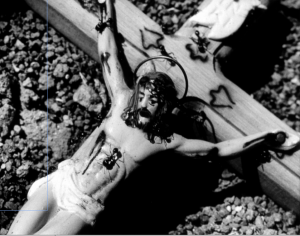

Wojnarowicz worked with one foot in culture and one in nature. He incorporated ants into his art. In his “Ant Series, 1988-89,” there are ants in the photographs Eye with Ant and Desire, which has an ant crawling on a crotch. Insects were integral to his personal symbolism, with ants the closest analogue to human existence. Carr described his fascination with ants thus: “When he went to Teotihuacan late in 1986, knowing that he would find nests of fire ants among the Aztec ruins, he brought other props with him besides the crucifix (to represent spirituality). He also filmed and photographed ants crawling over watchfaces (time), coins (money), a toy soldier (control) and other charged symbols.”

An eleven-second clip of ants crawling over a crucifix from an incomplete four-minute video called “Fire in My Belly” was to be included in Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, a 2011 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Instead, the video was withdrawn from the exhibition amid protests outside the Transformer Gallery, which screened it for public viewing in their storefront window, and at the National Portrait Gallery. The video was a flashpoint that got the attention of the U.S. Congress when the Catholic League denounced the clip as blasphemous and demanded that all funding be withdrawn from the Smithsonian. Twenty years earlier, in 1990, in a legal suit against the American Family Association, Wojnarowicz was granted a court injunction to prevent distribution of a pamphlet with images of his work taken out of context in an attempt to defund the National Endowment for the Arts. The controversy was written about extensively (including in these pages, by Kat Long, in “Censorship at the Smithsonian,” March-April 2011) and widely condemned as a example of art censorship, specifically when the art explores same-sex sexuality, gender issues, and alternative sexualities in general.

The clip from the video became the most famous item in Wojnarowicz’ extensive body of work, which includes, in addition to his impressive portfolio of photographs, four books: Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991); Memories That Smell Like Gasoline (1992); The Waterfront Journals (1997); and In the Shadow of the American Dream: The Diaries of David Wojnarowicz (edited by Amy Scholder, 2000). These memoirs, with their intimate combination of personal, literary, and social insights, follow in the tradition of other GLBT and feminist figures who capture a particular era in their writings. One thinks of Keith Haring, whose journals, notebooks, and sketchbooks were part of Keith Haring: 1978–1982, a 2012 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. Others include Alison Bechdel, Lillian Faderman, Allen Ginsberg, Christopher Isherwood, Karla Jay, Robin Morgan, Adrienne Rich, Ned Rorem, Sarah Schulman, May Sarton, Gore Vidal, and Tennessee Williams.

That much of Wojnarowicz’ art is filled with loss and pain is unmistakable. If his personal demons weren’t enough, his sorrow and rage were concentrated by the unspeakable toll of AIDS, and by society’s unforgivable neglect of its victims. Wojnarowicz called his first memoir Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration to indicate living at “the edge of mortality … and dying is around everything,” selecting metaphors about things breaking apart and a loss of cohesion, and describing his art as “things that are like fragmented mirrors.” He was acutely aware of his own mortality, at times as a disembodied witness, at other times as a participant acutely aware of the disease process that was overtaking him, when he wrote about “living on borrowed time”: “I can almost see my own breath, see my internal organs functioning pump pumping.” In the Shadow of the American Dream he wrote: “I try to understand the sensation and keep thinking it has to do with my mortality, my slow death, my depressions in the last couple years. It feels like it keeps boiling down to my sense of mortality, the sense that no one else can touch something essential in me.”

Wojnarowicz’ photographs weren’t always made with activist intent, and he didn’t always think of himself as an activist. However, all his work is mediated to some degree by complex layers of symbolism and metaphor that can only be interpreted and understood through the lens of the AIDS epidemic. Wojnarowicz bore witness to the AIDS epidemic at its epicenter in the 1980s, much like the central figure in Albert Camus’ allegorical novel The Plague, who resolves to “bear witness in favor of those plague-stricken people, so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done them might endure.” Wojnarowicz’ dreams and symbols, while seemingly personal, are thoroughly embedded in the social history of that devastating era. To read Brush Fires in the Social Landscape is to relive a traumatic time of complete anxiety, an acute awareness of mortality, and the fear of abandonment, disfigurement, infantilization, stigmatization, and death.

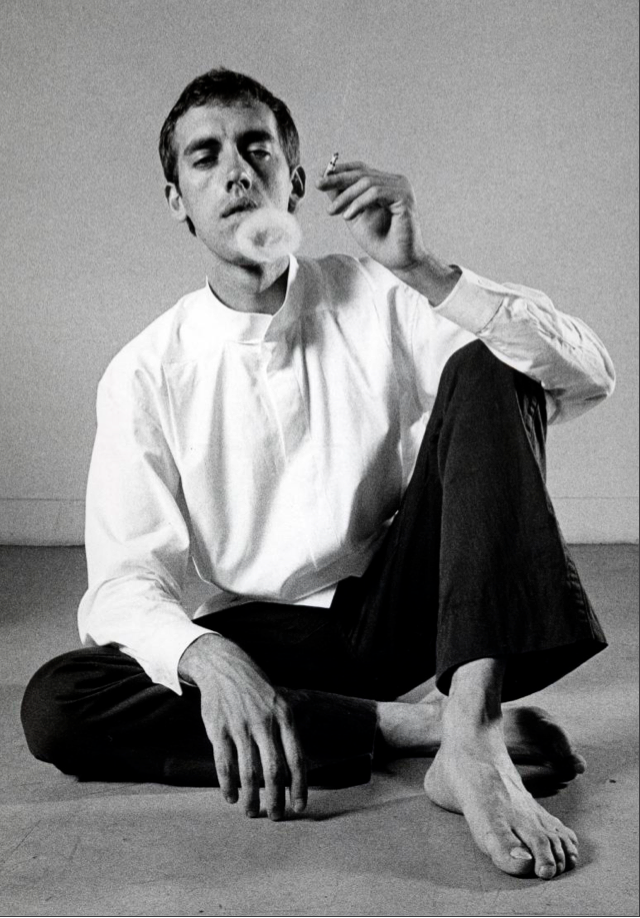

Wojnarowicz also documented, albeit unwittingly, the collapse of the gay subculture that had taken shape in the 1970s. His writing and art seem like an archeological excavation, the discovery of artifacts, neighborhoods, the vernacular of a previous era: cruising 42nd Street and Times Square, clandestine nightlife of the piers, docks, warehouses of Greenwich Village; after-hours hangouts, such as the Silver Dollar, a 24-hour greasy spoon on Christopher Street. The photographs also suggest the nascent exploration of queer identity and gender construction through various portraits and self-portraits contained in the book: Nan Goldin’s David Wojnarowicz at Home (1991), taken toward the end of his life, when he looked severely debilitated; or Emily Roysdon’s Untitled (needle) (2001-7), with his head on a woman’s body; or the mutual portraits by Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar, his lifelong friend and mentor who was also briefly his lover. They were subjects for each other—in acrylic, collage, film, silver gelatin prints, and text—of David, lighting up, smoking, or with a snake; of Peter, in found glasses, on his deathbed, levitating, or sleeping on the floor.

Excursus: On Photography

The OED defines the Latin saying “memento mori” variously as “remember to die,” “remember death,” or “remember that you must die.” Doubtless when the photogenic Susan Sontag wrote the following in On Photography, she was thinking of her own mortality: “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” Sontag also wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others, “Ever since cameras were invented in 1839, photography has kept company with death.”

The genre of postmortem photography was common in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Infant and child mortality rates were high, and often families would have a photograph taken before burial; many were face close-ups or full-body portraits. The deceased were arranged to appear asleep, but alive. Children were often shown on a couch or in a crib, posed with a favorite toy. When Sontag was dying, her partner, well-known photographer Annie Leibovitz, described taking pictures of her in A Photographer’s Life (1990-2005): “I forced myself to take pictures of Susan’s last days. Perhaps the pictures completed the work she and I had begun together when she was sick in 1998. I didn’t analyze it then. I just knew that I had to do it. … I cried for a month [while editing the pictures]. I didn’t realize until later how far the work on the book had taken me through the grieving process.”

A similar artistic process is described by Don Bachardy in the documentary Chris & Don: A Love Story. Bachardy, an accomplished portrait artist, discusses the last six months of Christopher Isherwood’s life as a daily task during which he made nine or ten pictures every day. “I was being an artist, but at the same time I was dying with Chris. … I was shocked that I could do such a stark picture of Chris. … I spent the day drawing his corpse. … I wasn’t sure I had the courage to do it. … He would have been cheering me on. He would say, ‘Yes, that’s what an artist would do.’”

In Love, Mortality and the Moving Image, Emma Wilson defines this process as “a means of maintaining a sensory, amorous relation to the dead. … If art offers palliation, it does so in the most gripping, intimate and unorthodox ways.”

Immortalizing the Dead

Of this palliative experience—being queer, holding on to relationships, and being an outsider—Wojnarowicz wrote in Close to the Knives about the 1987 death of photographer Peter Hujar, who was briefly his lover and who became an artistic mentor. Despite his grief, or perhaps because of it, Hujar’s death became mythic to him, and he historicized it immediately, representing it through various mediums and metaphorically (see photo at left), writing:

His death is now as if it’s printed on celluloid on the backs of my eyes. … I surprised myself: I barely cried. When everyone left the room I closed the door and pulled the Super-8 camera out of my bag and did a sweep of his bed: his open eye, his open mouth, that beautiful hand with the hint of gauze at the wrist that held the IV needle, the color of his hand like marble, the full sense of the flesh of it. Then the still camera: portraits of his amazing feet, his head, that open eye again.

Wojnarowicz filmed Hujar’s body on his deathbed, photographing individual body parts, a close-up of his face, hands, and feet with rigor mortis beginning. In her essay “Some Sort of Grace: David Wojnarowicz’ Archive on the Death of Peter Hujar,” Emily Colucci explained this image-making as the creation of “an affective space for representing queer intimacies through a melancholic struggle with loss.”

In every momentous social crisis, artists emerge who use their gift to frame a moral dilemma, whether in words, music, or visual representation, not solely by recording it as it unfolds, but by taking a stand that could influence the course of the crisis itself. In Poetry and Commitment, Adrienne Rich asserted that, “For now, poetry has the capacity—in its own ways and by its own means—to remind us of something we are forbidden to see.” Wojnarowicz spent his brief lifetime formulating an innovative visual grammar and promoting its moral function by going where the camera could not.

Steven F. Dansky, an activist, writer, and photographer for fifty+ years, is the founder of Outspoken: Oral History from LGBTQ Pioneers.