CATHERINE DE’ MEDICI, Dowager Queen of France in the age of Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Rabelais, had bad luck with her sons. Although each was to ascend a throne, as Nostradamus had predicted to her, each came to a sticky end. François II died in a freak jousting accident. Charles IX succumbed to a “bloody flux” (some said he was poisoned). And Henri III (1551–1589) was assassinated by a religious fanatic.

This last fate is the least surprising, for it was an age of religious wars. Catholics and Protestants were at one another’s throats all over Christendom. At his mother’s instigation, Charles had unleashed the Saint Bartholomew’s Massacre, which slaughtered thousands of French Huguenots. Both the Catholic Duc de Guise and the Protestant Admiral Coligny were savagely murdered after previous attempts. The recent invention of movable type allowed all factions to print cheap broadsides and caricatures inflaming passions by demonizing their opponents as misbegotten monsters. It was amid this welter of blood and calumny that the modern image of the effeminate homosexual took shape.

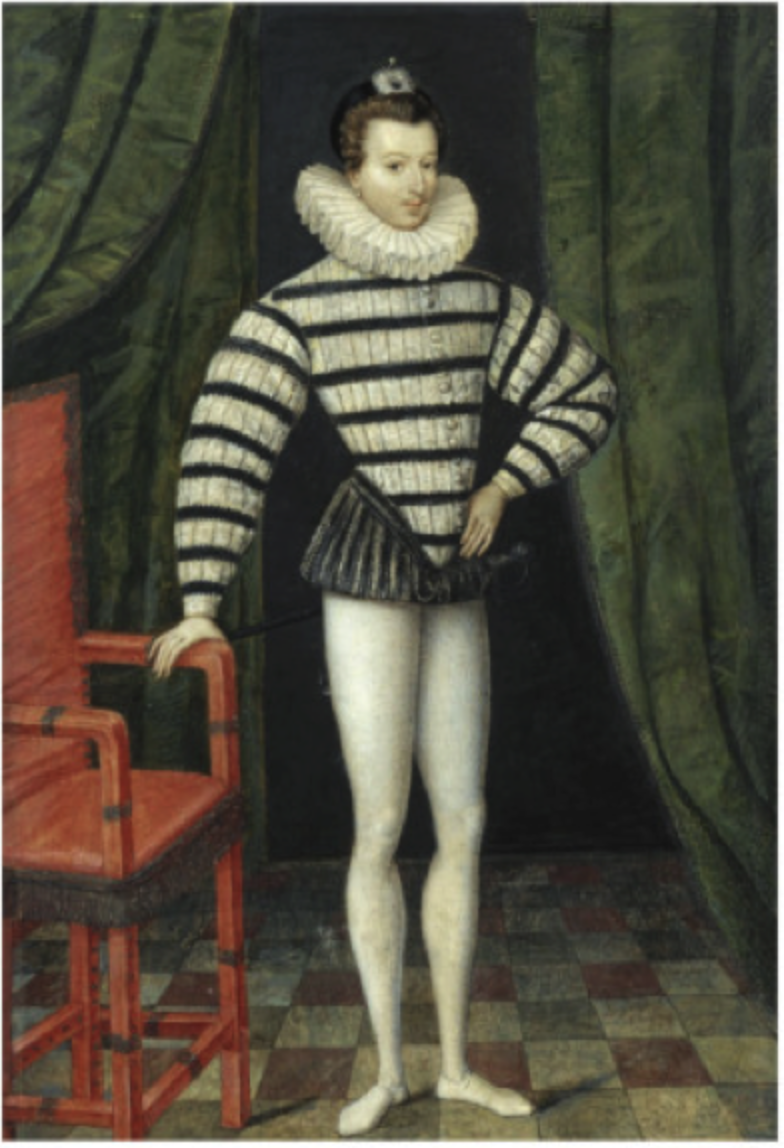

Henri had just been elected King of Poland in recognition of his military valor when he was recalled to Paris in 1574 to replace his dead brother (Figure 1). He was soon under attack from both camps. Even before his coronation, outside observers had commented unfavorably on Henri’s appearance, his unmanly demeanor, and such pastimes as masquerade cross-dressing. Giovanni Correr noted in 1569 that he “sta volontieri fra le dame” (likes to hang out with the ladies), and the Venetian ambassador Giovanni Michieli reported in 1572 that “he keeps for the most part among the ladies, dowsing himself in perfume, reeking of scent, primping and curling his hair, putting pendants in his ears [which, another ambassador commented, were pierced] and rings of all sort. You have no idea the prices he pays for the beauty and elegance of his shirts.” (See Figure 2.)

Henri’s innovations in court etiquette, his sartorial refinements, and the intensity of his male friendships expressed his tastes, but were also part of his policy. Often based on Italian practice, they were marks of elitism, a prerequisite to entering the world of high politics. As his reign began, these whimsies raised eyebrows but not ire. Gradually, his “leadership style” provoked

greater dissatisfaction, and Henri’s eccentricities came to be deplored by the middle classes and the lower echelons of the clergy. Despite heavy censorship and laws against press freedom, sermons fulminated against the king and lampoons flourished. By 1577, a police edict admitted that banned satires were selling better than ever, circulated by itinerant peddlers.

Both in words and images, the strongest attacks excoriated the “effeminacy” of Henri and his immediate circle, the “mignons.” The term “effeminé” had only recently come into usage and was ambiguous in its meaning. Effeminacy commonly implied lust and over-indulgence in sensual pleasures. One could become effeminate from too much intercourse with women, since women were believed to be more sexually active and avid than men.

“Mignon” as it appears in Rabelais simply means a companion or, as “mignon de couche,” a woman’s bedfellow. By July 1576, when the Parisian burgher Pierre de L’Estoile first notes it in his diary, the word had become current as a scornful term for the king’s favorites:

Two of L’Estoile’s accusations became fixtures in the charge sheet against Henri’s effeminacy: dancing and extravagant dress. The first complaint was leveled at Henri for his alleged fragility and lack of aptitude for blood sports and athletic contests, a considerable blemish in the eyes of men of war. The mignons’ preferred wardrobe also sinned against masculine taste. They rejected pumpkin-shaped trunk hose in favor of tightly fitting briefs pleated like women’s undergarments. The doublet was finished with puffed, slashed sleeves narrowed at the wrist and an immense ruff, raised at the back, which was later replaced by a fan of lace stiffened with brass wire. Hair was worn en raquette (like a battledore or tennis racket), swept up and off the forehead. A large chignon of false hair was secured by an ornamental comb and covered by a snood or tiny bonnet adorned with an ostrich feather. All this was set off with drop-earrings of pearls or precious stones, expensive pendants on the forehead, Italian shoes, gold chains, and gloves that were never removed. The style emphasized slender waists, long legs, and narrow faces enhanced by make-up—not at all a warrior’s physique (Figure 3).

Henri and his courtiers were also accused of being neat and clean, another unmanly trait. Anyone who turned up in court messy or unbuttoned was reprimanded. The King, according to one biographer, “infinitely loved cleanliness and no one entered his chamber who was not in white pumps or black velvet mules, with gartered stockings or other garments which had to maintain an extreme fastidiousness.” His favorites, chosen for their youth and elegance, were constantly on display and had to keep to these rules of decorum in order to maintain the royal ideal.

Outside the court, such delicacy was subject to ridicule. Sartorial refinement was equated with lack of virility. In Noël du Fail’s Contes d’Eutrapel, an old captain rails at a “mignon ainsi effeminé, frisé, enchiffré, godronné” (“a mignon so effeminate, curled, padded and goffered to the nines”): “Ha, my pretty boy, my good friend, my little parrot mignon … you have but the strength of a plucked blackbird, and … long story short, if you shot your spunk in my soup, I’d eat less of it.”

Neither Henri’s contemporaries nor latter-day historians have been able to prove actual same-sex activity on his part; he seems to have enjoyed relations with both his wife and his mistresses. The discreet L’Estoile does not specify sexual misconduct but infers it from the elaborate dressing, whorish cosmetics, lavish spending, and unseemly contortion of the body in acrobatic dancing. The words “bougre” and “bougeron” begin to appear more frequently in the lampoons, along with references to Ganymede and “masculine love.” L’Estoile cites a sonnet of 1577 that claims the mignons “Duplicate Ganymede, overturn nature.” Even the loose breeches sans codpiece popular in Henri’s reign became known as “chausses à la bougrine” or “buggerlets’ hose.”

Others were willing to be much more scabrous. In the most ribald lampoons, mignons are called “cunts.” Sodomy is no longer a blanket term for inadmissible sex acts but refers specifically to buggery. A sonnet attributed to Pierre Ronsard could not be more graphic:

The king does not like me to be too hairy:

He loves to sow the field which is not grassy.

And like the beaver straddles the backside:

Whenever he fucks arses which are contracted cunts

He takes after those Italian de Medicis

And imitates his father only from the front.

Those arses turned cunts swallow up more goods

Than the gulf of Scylla did the Ancients.

The imputation of sodomy to Henri III was meant to ostracize him from Catholic French society and its accepted values. The satirists were not simply exploiting a handy term of abuse. They were attacking what Joseph Cady terms “same-sex attraction as the kind of substantial and lasting desire we would now call an orientation. The idea of “homosexuals” with their own distinct culture was beginning to coalesce (Figure 4).

Before 1576, many of those who launched pamphlets against Henri III and his court were insiders, egged on by the outrageously swish Duc d’Alençon and Henri’s sister Marguerite of Navarre in a concerted effort to blacken the king’s image. Theirs was not so much a moralistic attack on vice as it was mud-slinging to tarnish a reputation. With its allusions to licentious characters of ancient times (Sardanapalus, Heliogabalus, Nero), their calumnies appealed mainly to a literate, aristocratic audience.

Later, the propaganda came primarily from Huguenot and radical Catholic sources, and it increased in virulence. With a popular audience in mind, it drew more on biblical or folkloric examples. Henri’s womanish ways had to be turned into symptoms of blasphemy and treason. After May 12, 1588, when the King was denounced from Parisian pulpits as an excommunicate heretic, the scurrility was ratcheted up to justify his ostracism. Literally to demonize Henri, witchcraft and sodomy were interwoven. A fifteen-page pamphlet charged him with overt Satanism practiced with his intimates, merging sorcery and homosexuality.

The militantly Protestant poet Agrippa d’Aubigné packed his libels with a medley of concrete and sensual metaphors, which converge in a hideously distorted portrait of Henri. The anathema uttered by D’Aubigné’s “poetics of the monstrous” is laid upon Henri’s mignons as well:

Ces hermaphrodites, monstres effeminés,

Corrompus, bourdeliers, et qui estoient mieux nés

Pour valets des putains que seigneurs sur les

hommes.

(“These hermaphrodites, effeminate monsters/ Corrupt, whore-mongers, and who were born better/ To be lackeys of strumpets than masters of men.”) The invective issuing from Parisian print shops bolstered resistance against the king throughout France and helped prepare the ground for his assassination in 1588.

After Henri’s death, this cocktail of the demonic, the freakish, and the effeminate was kept afloat by a lingering backwash of defamation. One pamphlet, issued in 1589, began with the standard account of his outrageous behavior. The king had been “so effeminate that he made up his face as women do, and the better to imitate them accoutered himself in their garb, and counterfeited their gestures and countenances.” The charge-sheet moves, however, from transvestitism to transsexuality—“and desired among his fondest wishes to be transformed into a woman, so as to experience the delights of the feminine sex.” The accusation against the King then mutates into a science-fiction scenario of a surgical sex change, whereby Henri the devil is literally neutered:

[H]e fantasticated in his mind that by artifice he might be transformed in shape, and the better to carry out his diabolic wish, he brought together all the most excellent surgeons, physicians and philosophers of his time, and allowed them to cauterize his body and make all the openings and wounds they wanted, so long as they enabled him to conjoin with man: in pursuance of which they carved him up in several places, and castrated him. But he remained in the end, by the dispensation of God, useless to both sexes.

However “diabolical” Henri’s desire to become enough of a woman to enjoy sexual congress with a man, the means he employs is not witchcraft but medical science. Thus is progress measured.

Hermaphrodites by Thomas Artus.

(Cologne: Heritiers de Herman Demen, 1724).

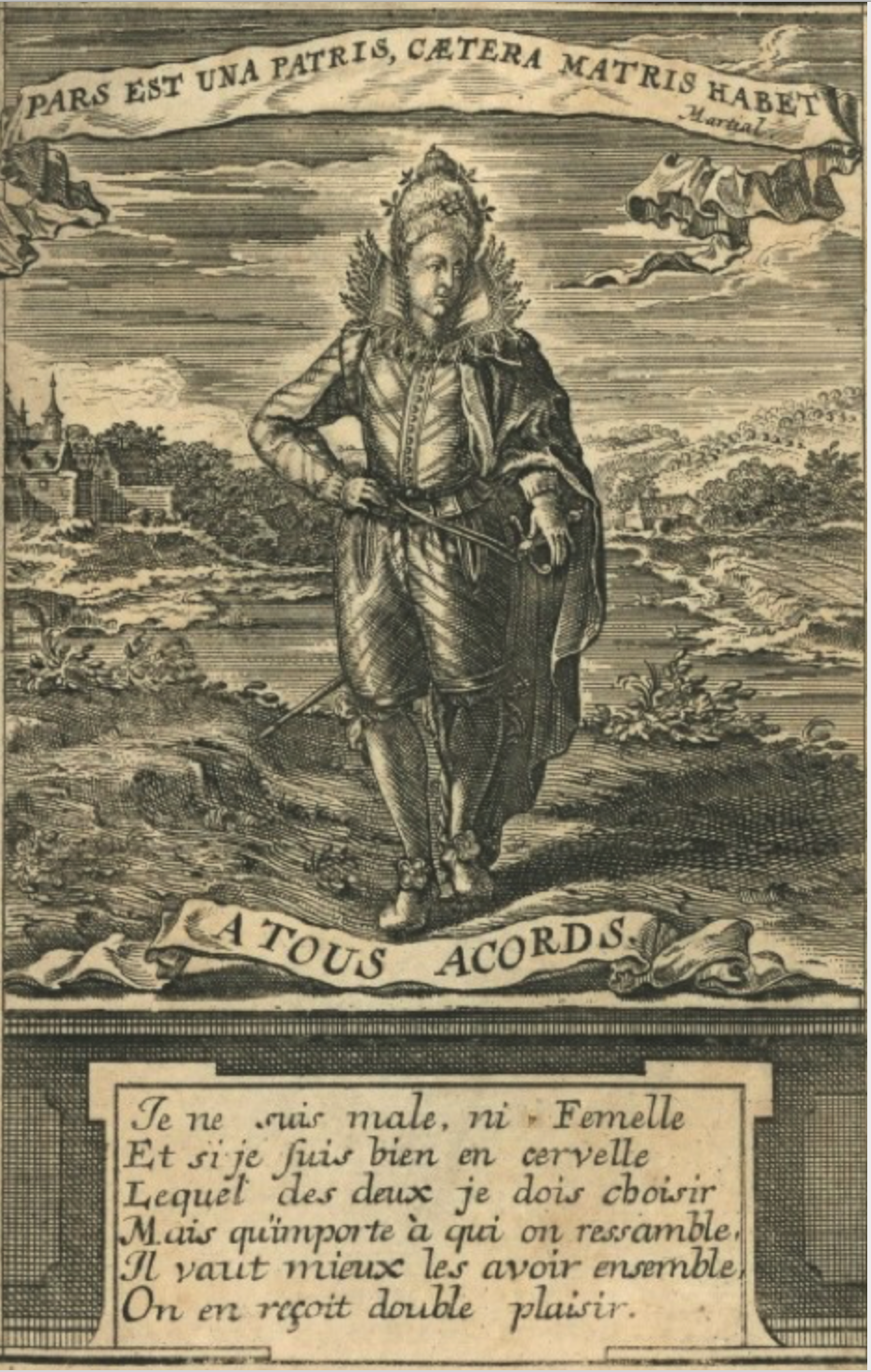

The fantastic element recurs, highly magnified, in a book which was once taken to be a satire of Henri III’s court, though it goes beyond this topical aspect to create a kind of homophilic dystopia. Les Hermaphrodites, by Thomas Artus, Sieur d’Embry, was published in 1605, a generation after Henri’s death. Artus’ romance has been interpreted as part of a smear campaign by Henri IV to denigrate his predecessor, and its much-reproduced frontispiece (Figure 5) has even been deemed a caricature of the last of the Valois. However, the suggestion that this book is a description of the “simperings and effeminate manners of the mignons” was not made until around 1700. Rather, it moves from a diatribe against a particular clique to a description of a new type of individual.

Whatever its source in the manners and morals of Henri’s court, Artus creates a self-sufficient, looking-glass world in which appearance replaces substance. Being and seeming are confounded. Like the mignons, the hermaphrodites of this island spend their time cultivating and showing off their façades. The heavily made-up face is a mask concealing a void. Disguise scrambles identity: veils, ornaments, coverings occlude reality. Artus’ narrator provides minute descriptions of clothing, cosmetics, hair, gestures, physiques and setting, even eating and communication. Each aspect of the external life of the hermaphrodite is ritualized:

Let sound be gentle, in its utterance, for fear of offending the delicacy of their ears, with bans of other sorts, whatever the matter, propriety or meaning there might be to the sense of what one says. … Each may dress according to his fancy, however bizarre the conceit may be, so long as the conceit has the virtue of what our foes call effrontery. … If cloth meant to be worked, however precious it is, be not enriched with an excess of gold embroidery, precious stones, pearls and that most often without moderation, we hold such accoutrements to be vile, trivial and unworthy of being worn by good company. …

The accoutrements which most approximate those of women, either in fabric or in fashion, are deemed by us the richest and more fitting, as the most proper to the manners, inclinations and customs of those of this isle.

Artus’ narrator is forbidden entry to a room where the beautified hermaphrodites engage in mysteries with their leader, so he is able to gauge their lewdness only from their gestures and conversations. He is, however, shocked by their “words of affection and fellowship” (de charité et de fraternité). This is a community whose language of camaraderie is incomprehensible to outsiders.

Soft, sibilant sounds, a private lingo, outrageously fanciful dress that smacks of feminine frippery, excess in adornment, secret gatherings suggestive of sex—a familiar figure is in the making. A historian of homosexuality in early modern France, Maurice Lever, claims that these neurotic flibbertigibbets, hysterical, narcissistic, affected, mincing, and ogling, are archetypes of a later caricature. “Just one word, a word of our times, can express such nauseatingly mannered infatuation, dim-witted pretension, snide backbiting beneath a constant smile of complaisance: la Folle!”

La Folle, which literally means “madwoman,” is French slang for a “screaming queen,” as in the popular film La Cage aux Folles. Another word for mignons had also been folets—“a prettie foole, a little fop,” a diminutive of fol which had also meant elf or fairy. Still, to dismiss the hermaphrodites in Artus’ colony (and with them the mignons surrounding Henri III) as mere precursors of flamboyant camp is to miss the more original and positive aspects of this fantasy.

Unlike Henri after his fictional sex change, “useless to both sexes,” these hermaphrodites enjoy to the full the duality of their persons. The frontispiece shows a fashionably dressed individual, wearing the cape, sword, doublet, and breeches of a well-born male, but the beardless face and upswept coiffure of a woman. The caption reads: “I am neither male nor female/ And yet I am in my right mind/ One of the two I am supposed to prefer/ But what does it matter which one resembles/ It is better to combine them both/ And double one’s pleasure.” This insistence on “ambisexterity” is repeated on the banderole above the hermaphrodite’s head. It reads not “Common accord” or “harmony,” which was the motto of androgyny, but rather “A tous accords,” which might be translated as “Ready for anything.”

Pleasure rules the roost in this realm. Artus deplores their hedonism, for the hermaphrodites pledge no allegiance to religion, sumptuary laws, or family ties. What Donald Stone calls their “egregious nonconformity that discounts every traditional norm” is a definition of self, to be explored through the senses. As one of the islanders explains, one gains self-knowledge not to achieve the humility ordained by religion, but rather to appreciate the self and promote its well-being. To this end, the senses are studied and cherished. This is a brand of humanism which stands outside divine order. Thomas Artus conceived of a world of adults, pursuing their pleasures to the cry of “I am what I am” long before it became the motto of gay urban ghettos.

Laurence Senelick is the author ofThe Changing Room: Sex, Drag and Theatre and Lovesick: Modernist Plays of Same-sex Love.

Discussion2 Comments

It was Catherine de Medici’s husband Henry II of France who died in a “freak jousting accident””, not her son Francois II. He died of an Ear infection at age 16.

The error was noted in the Sept-Oct issue.