Editor’s Note: This is the final of three parts of an essay about American dance and arts impresario Lincoln Kirstein (1907–1996). Having published a biography of Kirstein in 2007, Martin Duberman recently discovered a treasure trove of hitherto unseen letters and other personal writings that reveal much about Kirstein’s state of mind as he mingled with many of the leading choreographers, composers, writers, and artists of the Modernist era.

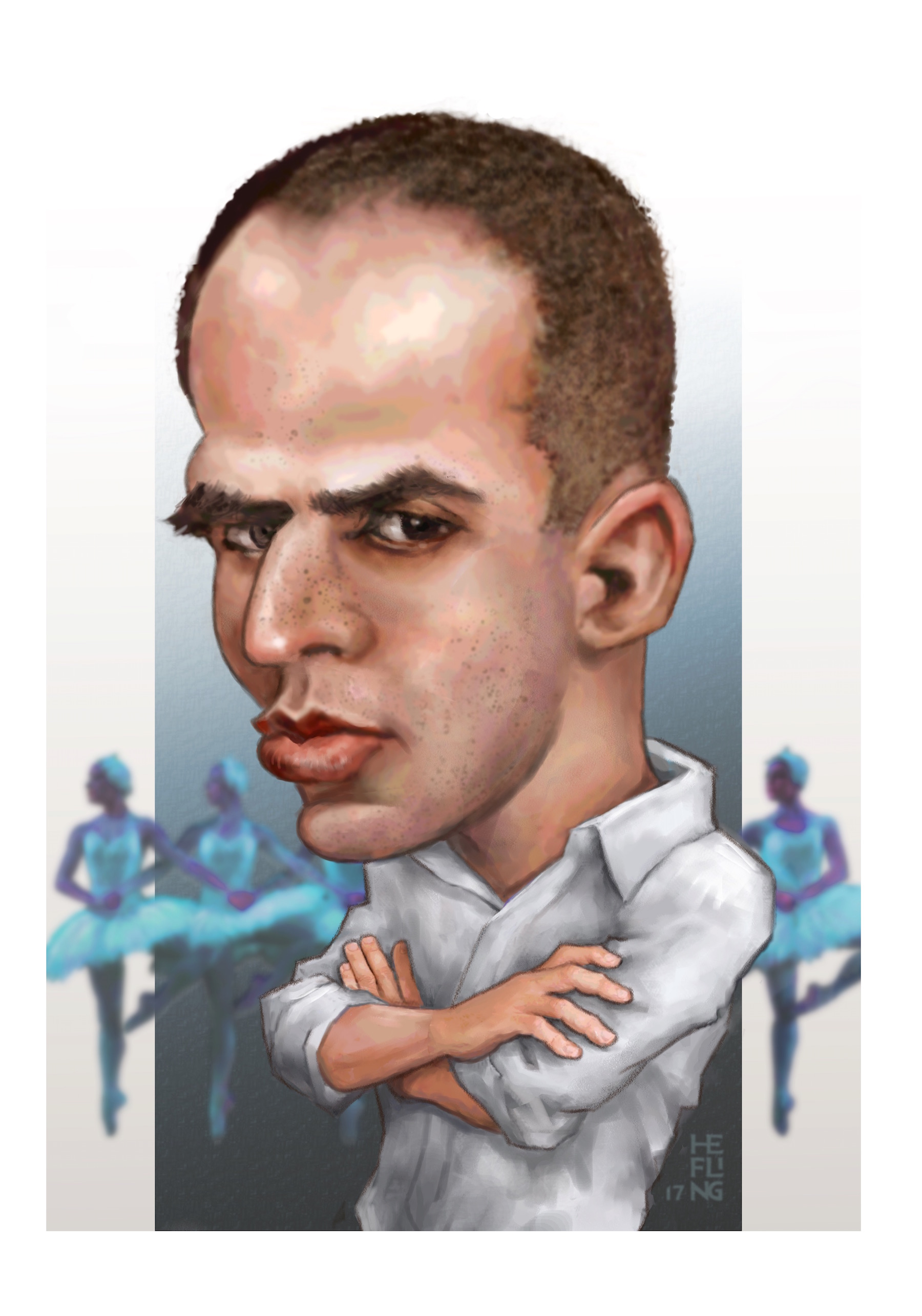

The first part (Jan.-Feb. 2017) focused on Kirstein’s productive but vexed relationship with George Balanchine, with whom he founded the New York City Ballet. The second (May-June) delved into his personal life and his many friendships with famous artists, including his love affairs with some of them. The final part continues this theme with a special focus on artists that Kirstein disdained (writers Glenway Wescott and Edith Sitwell, composer Marc Blitzstein), his longtime relationship with painter Pavel Tchelitchev, and his connection to two writers whom he greatly admired: E. M. Forster and W. H. Auden.