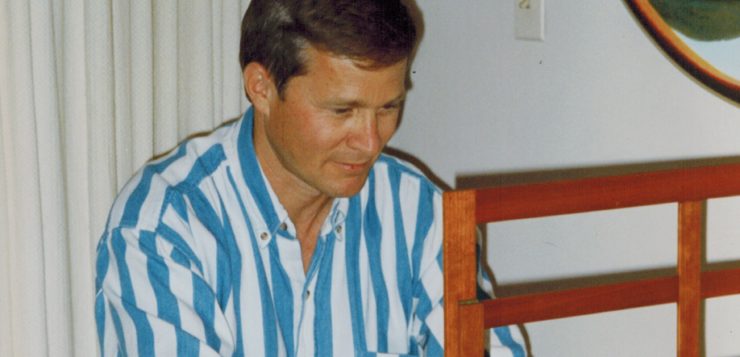

THIS MAGAZINE would not exist were it not for Ellis L. Phillips III, known to the world as “Larry” but to me as “Lars,” which is how I’ll refer to him here, with your indulgence. It was Lars who recruited me to join an alumni organization and take over the editing of its quarterly newsletter, which became the incubator for The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review, whose first issue was Winter 1994. Thus he was the critical connection that made it possible and was a major inspiration for the magazine’s early development.

THIS MAGAZINE would not exist were it not for Ellis L. Phillips III, known to the world as “Larry” but to me as “Lars,” which is how I’ll refer to him here, with your indulgence. It was Lars who recruited me to join an alumni organization and take over the editing of its quarterly newsletter, which became the incubator for The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review, whose first issue was Winter 1994. Thus he was the critical connection that made it possible and was a major inspiration for the magazine’s early development.

He was also my best friend.

Ellis Laurimore (where “Larry” came from) was born on Groundhog Day, 1948, and left us on Halloween, 2018—two pagan holidays; I’ve no idea what this means. He made it to age seventy, which is pretty great for a person of his generation with Type 1 diabetes, that cruel chronic disease that science hasn’t quite been able to neutralize, though Lars himself was acutely aware of, and grateful for, the genius of modern medicine that made his survival possible (synthetic insulin!). The cruelty of Type 1 is that the damage from sugar highs and lows over a lifetime is cumulative and systemic, the loss of faculties slow but inexorable.