The Leonard Bernstein Letters

The Leonard Bernstein Letters

Edited by Nigel Simeone

Yale. 606 pages, $38.

EDITOR Nigel Simeone has selected some 650 letters for this collection of Leonard Bernstein’s correspondence over a span of six decades of the 20th century. The first letter is from 1932, written by a fourteen-year-old Bernstein to his piano teacher, Helen Coates. The last is from 1990: a letter to conductor Georg Solti.

Needless to say, Leonard Bernstein’s correspondents include a “who’s who” of 20th-century musical, literary, political, intellectual, and newsworthy figures: composers Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, Marc Blitzstein; conductors Dimitri Mitropoulos, Serge Koussevitzky, Bruno Walter; actors Judy Holliday, Farley Granger (with whom he purportedly had an affair), Bette Davis; writers Thornton Wilder, James M. Cain, Martha Gellhorn (one of Hemingway’s former wives). In addition, there are the musical collaborators: Adolph Green and Betty Comden from On The Town; Arthur Laurents and Stephen Sondheim from West Side Story; and choreographer Jerome Robbins, with whom he worked on Fancy Free, West Side Story, and The Dybbuk. Among the entertainers with whom he corresponded were singers Lena Horne and Frank Sinatra and jazz legends Miles Davis and Louis Armstrong.

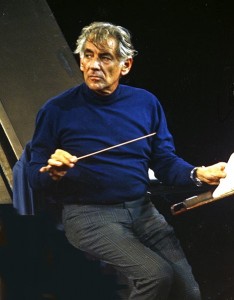

From these letters, Bernstein emerges as a highly intelligent, emotional, impossibly busy, incredibly gifted individual. His musical interests ranged from sacred classical to Broadway lite, while his professional life divided itself more-or-less equally between conducting and composition. Bernstein himself was acutely aware of his scattered interests and sometimes wondered whether he’d sacrificed a “great” career as a classical composer in pursuit of a public life as a conductor, teacher, and lecturer. Offsetting that concern was an authentic lust for life that led him to grab for everything within reach, musically and otherwise. His personal life included a loving marriage to a woman, children, extra-marital affairs with men, and a long-term relationship with a man.

From these letters, Bernstein emerges as a highly intelligent, emotional, impossibly busy, incredibly gifted individual. His musical interests ranged from sacred classical to Broadway lite, while his professional life divided itself more-or-less equally between conducting and composition. Bernstein himself was acutely aware of his scattered interests and sometimes wondered whether he’d sacrificed a “great” career as a classical composer in pursuit of a public life as a conductor, teacher, and lecturer. Offsetting that concern was an authentic lust for life that led him to grab for everything within reach, musically and otherwise. His personal life included a loving marriage to a woman, children, extra-marital affairs with men, and a long-term relationship with a man.

Bernstein’s struggle with his sexuality is a theme that runs through many of the letters. He was attracted to men but wanted a traditional family with a wife and children. After an on-again, off-again engagement, he finally decided to marry Felicia Montealegre, a Chilean actress and musician. She adored him but also knew of his sexual proclivities. She wrote to him (1951-1952): “you are homosexual and may never change. … I am willing to accept you as you are … our marriage is not based on passion but on tenderness and mutual respect.” Surprisingly enough, this understanding actually worked. The couple stayed together for decades, and they even had a few children along the way. Bernstein’s conducting schedule was such that he’d have to be marked down as a “mostly absent” father. He did his best to stay in touch with the family through copious newsy letters, many of which appear in this volume.

It was only in the mid-1970s that Bernstein finally left Felicia to take up with Tom Cochran, who’d been his de facto lover since 1971. But soon Felicia was stricken with cancer—the suspicion has lingered that somehow it was a direct result of her husband’s departure—so Bernstein moved back home and saw her through until her death in 1978. He was devastated by her demise and lamented that she never forgave him for having left. However, her departure does seem to have freed something in Bernstein, who now became, at the age of sixty, much more open about his homosexuality. (By the way, Simeone does not include any material related to Bernstein’s relationship with Tom Cochran, which seems an odd omission.)

A general impression one gets from these letters is the sense that Bernstein wanted to be loved by everyone, and that he drove himself mercilessly to this goal, however unachievable. A work titled “Bernstein Agonistes” would depict a man torn by inner conflicts involving his need to be everything to everyone. He always felt that he wasn’t doing enough. When composing, he wondered if he should be conducting; when writing musicals, he felt he should be working on an opera.

Added to the mix was Bernstein’s Jewish identity. He needed to prove himself as a Jewish man in a world that was still quite anti-Semitic. Excused from military service during World War II due to health problems, he learned from afar about the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. When he conducted in Vienna and in Bayreuth, Germany, Jews all over the world felt a sense of pride in his triumph. In my own family, Bernstein was worshiped as a “Jewish boy who made good.” His Young People’s Concerts and his Omnibus Series were must-hear events at our house. My mother bought tickets to see West Side Story on Broadway within the first month of its opening.

Behind the scenes, the letters about the making of West Side Story will be of great interest to anyone who’s a fan of the brilliant musical. We learn about the difficulty that Bernstein had collaborating with Jerome Robbins, who was notoriously difficult to work with, and that he almost quit the show because of Robbins.

Now for a couple of complaints about this book, as well-produced as it generally is. Simeone does not include many letters from Bernstein’s later years. There are no letters about his refusal to accept the National Medal of Arts from President George H. W. Bush as a protest against the revocation of an NEA grant for an AIDS exhibit when it was learned that the show featured works by Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano. A second quibble is that the footnotes are often unnecessarily long and compete for space with the letters themselves.

Those peccadilloes aside, The Leonard Bernstein Letters opens a window into the world of one of the most accomplished and brilliant artists of the 20th century. His letters reveal his search for meaning through his involvement, not with abstract ideas for the most part, but with the flesh-and-blood world of family, friends, lovers, and, of course, his music.

Irene Javors, author of Culture Notes: Essays on Sane Living (2010), is on the faculty of the Mental Health Counseling Program of Yeshiva University in New York City.