Editor’s Note: What follows is excerpted from a longer piece that will soon appear in The Line of Dissent, a collection of the author’s essays published in this magazine over the years. Some of the material that follows has previously appeared in these pages (in 2017)—in a three-part essay on impresario Lincoln Kirstein, who cofounded the New York City Ballet with George Balanchine—but much of it is brand new.

BY 1933, Lincoln Kirstein’s long-simmering search for a way to establish a classical ballet company in the United States picked up steam and intensity. His interest in the ballet had initially quickened on his various trips to Europe as a teenager, when he’d seen Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. That same year, 1929, with Diaghilev’s death, the ballet world had become rent by factions. A number of émigré artists had been trying to lay claim to his mantle, and to find venues, patrons, and, they hoped, companies that might make their existence less precarious.

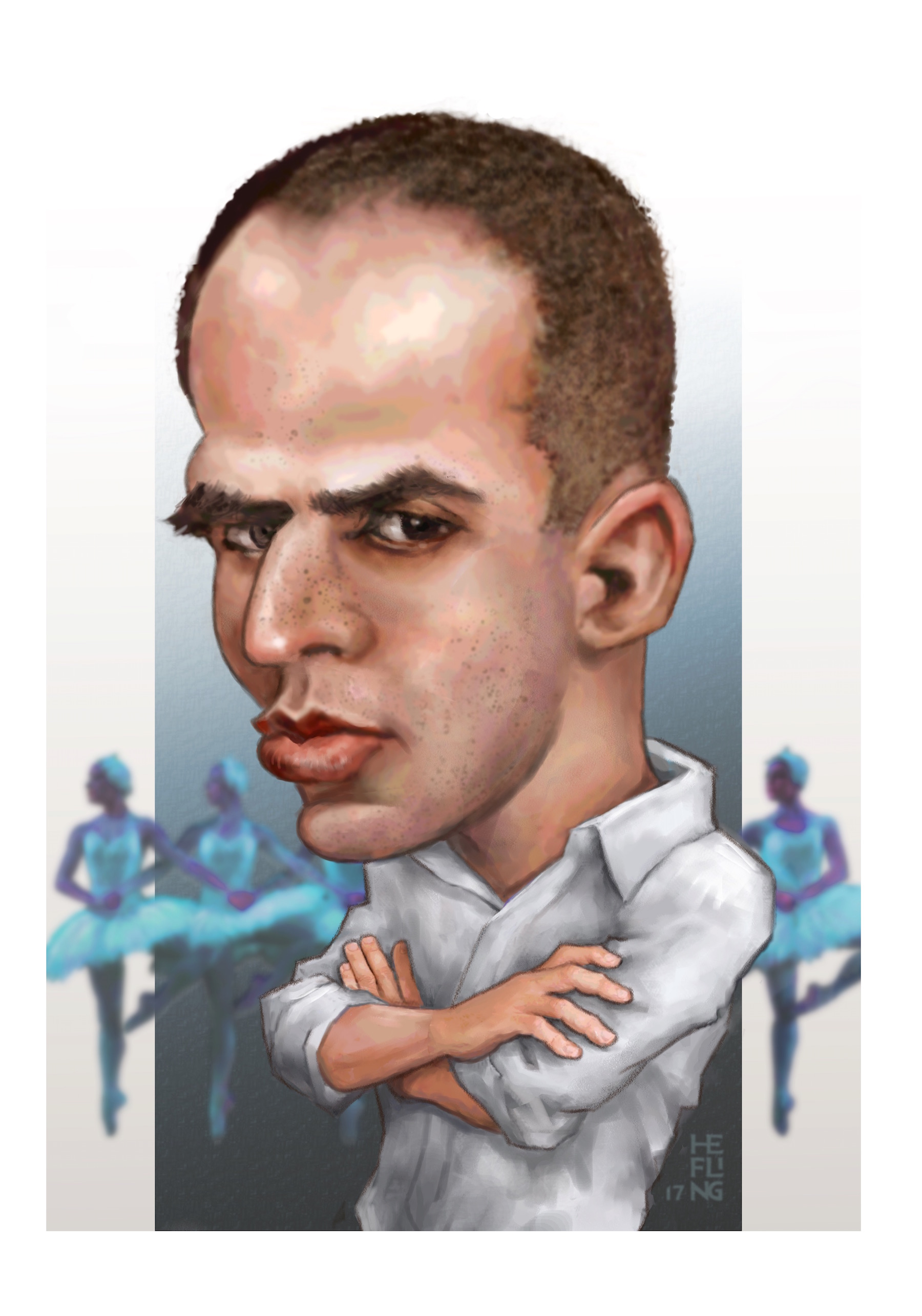

George Balanchine, who’d been Diaghilev’s last important choreographer, succeeded in putting together a group called Les Ballets 1933, a young company of some fifteen dancers, including Toumanova, Derain, and Roman Jasinski. None of this would have come to pass had it not been for the events of a decade earlier, when Vladimir Dimitriev, a former baritone in the Mariinsky opera company, successfully engineered exit visas from the Soviet Union for a small group of artists, the so-called Soviet State Dancers. Among them were Balanchine, Tamara Geva, his first wife, and the ballerina Alexandra Danilova, who would become his “unofficial” second wife.

George Balanchine, who’d been Diaghilev’s last important choreographer, succeeded in putting together a group called Les Ballets 1933, a young company of some fifteen dancers, including Toumanova, Derain, and Roman Jasinski. None of this would have come to pass had it not been for the events of a decade earlier, when Vladimir Dimitriev, a former baritone in the Mariinsky opera company, successfully engineered exit visas from the Soviet Union for a small group of artists, the so-called Soviet State Dancers. Among them were Balanchine, Tamara Geva, his first wife, and the ballerina Alexandra Danilova, who would become his “unofficial” second wife.

Kirstein went up to Hartford to see his friend Chick Austin, the youthful head of the prestigious Wadsworth Athenaeum, who showed him the half-completed new International Style addition to the museum. Kirstein noted in his diary that “his little auditorium is perfect for small ballets.” Austin, like Kirstein, was a serious advocate of the arts and an audacious innovator. As director of the Athenaeum, he’d transformed Hartford’s reputation as the stodgy headquarters of the insurance business into an important center of cultural ferment. Kirstein knew that, although Austin was married, his erotic preference was homosexual, and he hinted to Kirstein, who also preferred men, about having recently indulged in “some highly irregular pleasures,” saying that he’d tell him more some other time.

§ When in Europe during the summer of 1933, Kirstein—age 26 at the time—met with Balanchine, and the two had “a long and satisfactory talk” in French. Kirstein found him “wholly charming.” A few days later, they had lunch, Balanchine arriving nattily dressed in a gray flannel suit, “his strong, delicate Caucasian face very animated” (as Kirstein wrote in his diary). They talked in some detail about the possibility of an American ballet, with Kirstein briefly mentioning Chick Austin’s museum in Hartford as a possible site. “We got frightfully excited about it all,” Kirstein wrote in his diary. “I visualized it so clearly. He wants so much to come … says it has always been his dream. He would give up everything to come.” Kirstein then got “frightfully worked up” and, able to “think of nothing else,” sat down and wrote his now famous sixteen-page letter to Austin. It began with a grand theatrical flourish: “This will be the most important letter I will ever write you … my pen burns my hand as I write: words will not flow into the ink fast enough. We have a real chance to have an American ballet within 3 years time. When I say ballet, I mean a trained company of young dancers—not Russians—but Americans with Russian stars to start with.” Years later, Kirstein claimed that he’d deliberately chosen “an optimistic style” in writing to Austin. But “calculated optimism” doesn’t capture a tone that sings with ardent intensity; his words leap off the page with an almost libidinous passion. “You will adore Balanchine,” he tells Austin. “He is, personally, enchanting—dark, very slight, a superb dancer and the most ingenious technician in ballet I have ever seen.” Then, knowing his audience, Kirstein appealed to Austin’s homoerotic side by describing Roman Jasinski, likely to be the new company’s male star, as “extremely beautiful—a superb body.” There had been earlier attempts to find a home for ballet in the U.S., but—while Anna Pavlova (from 1910 to 1925) and a few other internationally famous stars had successfully drawn audiences—there had been few opportunities to study classical technique and a scant tradition of indigenous choreography. Kirstein insisted to Austin that the planned-for school “can be the basis of a national culture as intense as the great Russian Renaissance of Diaghilev. We must start small. But imagine it—we are exactly as if we were in 1910. … Please, please, Chick, if you have any love for anything we do both adore, rack your brains and try to make this all come true. It will mean a life work to all of us [and]incredible power in a few years.” He assured Austin that he was not being “either over-enthusiastic or visionary.” But of course he was being both. Drunk on possibilities, perhaps feeling it might be now or never, Kirstein couldn’t help throwing caution—along with absolute truthfulness—to the wind. Even if he’d been capable of a more modulated tone, it might not have appealed to Austin’s own audacious nature. Bravado and amplitude were mother’s milk to both men. If Austin was going to bite, the nervier the vision, the better. § In the first few years following Balanchine’s arrival in the U.S. late in 1933, Kirstein wholly immersed himself in the back-to-back crises, artistic and personal, that seemed to descend without letup, and which threw into serious doubt the entire notion of forming an American ballet. For much of the first year, Balanchine’s precarious health threatened to sink the ship; he himself tended to minimize the seriousness of his condition, but Kirstein knew better and had to constantly play nursemaid, ensuring Balanchine’s comfort, watching over his diet, shuttling him from one doctor’s office to the next—even as he puzzled over the specialists’ contradictory diagnoses. At one point a specialist found “two active but diminishing spots” on Balanchine’s lungs and prescribed injections of insulin that the previous specialist had advised against. To avoid alarming the patient, Kirstein—even while fretting over the contradictory diagnoses and elusive prescriptions—had to control his own, not inconsiderable, mood swings. (Later in life, he’d be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. When W. H. Auden was at one point asked about Kirstein’s “erratic” behavior, Auden replied: “everyone has moods and Lincoln’s should be respected. Lincoln always means well … he’s a very good man.”) When his health finally stabilized, Balanchine had a burst of creative energy, and no one was more thrilled than Kirstein. For three years in the early ’30s, Balanchine and the fledgling company (which called itself the American Ballet) provided the dance interludes at the Metropolitan Opera, which led to a full-scale production of Balanchine’s Orpheus (with Tchelitchev’s set and costume designs). As a result, Balanchine started to get commercial offers and he signed on to do a Broadway show, On Your Toes, which proved an enormous success. That, in turn, led to still other assignments to choreograph musicals, including Rodgers and Hart’s Babes in Arms. Despite this success, Balanchine’s prime interest remained what it always had been: creating an American ballet school and company. His detour to Broadway alarmed Kirstein, even as it gave him more of a chance to exercise his own talents. Picking from among some dozen dancers already attached to the American Ballet, he formed a touring company, Ballet Caravan, which toured the country for a few months of each year for four years. Kirstein’s conviction that Balanchine stood head-and-shoulders above all other choreographers hadn’t weakened: the Caravan primarily performed and spread awareness of the master’s genius. That genius, in Kirstein’s view, was uniquely centered on the virtuosic body in stark, swift motion, unconnected to sentimental narration, with movement an end in itself. At the same time, Kirstein initially hoped to include ballets that had at least the outlines of a traditional storyline, and, in particular, with identifiably American content that referenced everyday life. With Ballet Caravan under his exclusive control, it became possible for Kirstein to commission works with a strong narrative line. Many of these ballets have become standards in the repertoire: Lew Christensen and Elliott Carter’s Pocahontas; Eugene Loring and Paul Bowles’ Yankee Clipper; Christensen and Virgil Thomson’s Filling Station; and Loring and Aaron Copland’s Billy the Kid. Kirstein continued to value Balanchine’s genius, but, thanks to the new letters that have turned up, we now know that his experience in running the Caravan gave Kirstein a new confidence in his own judgment. In a letter to Tchelitchev, Kirstein vowed that henceforth he would “criticize and be harsh with him [Balanchine] when I feel like it … instead of being scared by his uniqueness and genius.” Yet ironically, by the time Balanchine had had his fill of Broadway and returned full-time to the American Ballet, Kirstein’s interest in exploring the American past through dance had sharply diminished. It wasn’t a matter of Balanchine compelling adherence to his neoclassical vision, but rather the result of Kirstein’s lessening involvement in left-wing politics after the 1930s, and a diminished interest in American-themed narrative dance. Unlike Kirstein, Balanchine had always been politically conservative and deeply religious, and when he turned, briefly, to American subjects in the ballets Western Symphony (1954) and Stars and Stripes (1958), it would be in a spirit of joie de vivre rather than moral earnestness. Kirstein had also come to realize that he was temperamentally ill-suited to the many demands of managing a touring company. Harvard’s Houghton Library’s new collection of family letters tells us a good deal more than we’ve previously known about the multiple responsibilities of running a ballet company and the demands it made on Kirstein’s limited patience for the mundane details of daily life. Brilliant, deeply serious, and widely read, Kirstein never lost his “affection” for the Caravan and its accomplishments but, especially during the last year of touring, he developed, to his own surprise, “certain sudden murderous instincts” toward his “little troupe.” “I can’t stand easily,” he wrote home, “the unremitting gaiety and good clean fun of one and all.” After the touring finally came to an end in 1938, Kirstein suddenly came up with a new idea, one that might, on the side, serve as a more creative outlet than “laying out the master’s clothes.” Still interested, if to a lesser degree, in left-wing politics—much later, he would join the Selma March—he came up with a “divine” idea for a new ballet he called “Memorial Day.” Its theme would be “democracy in crisis,” as represented through Civil War iconography. He planned to write the libretto himself and asked his friend Aaron Copland (with whom he would always have a good relationship) to write the score—a commission Copland accepted enthusiastically. For a time, the project consumed Kirstein; he sent his sister Mina letter after letter (all in the new Houghton collection) detailing his progress and using her as a sounding board for his ideas. He was especially keen to get Mina’s take on getting the prestigious Mercury Theater involved. John Houseman (who’d been Mina’s lover) had in 1937 cofounded the Mercury with 21-year-old Orson Welles, and Kirstein hoped Mina’s influence would lead Houseman to produce Memorial Day first as a concert and then as a theatrical run. Though Mina had also come through at the last minute with a crucial donation that allowed the legendary John Houseman-Marc Blitzstein production of The Cradle Will Rock to open, she wasn’t able to interest Houseman in Memorial Day. In the upshot, Kirstein revised and redrafted his libretto for Memorial Day, accepting many of Mina’s suggestions for revision, though he came to see the whole project as “very pretentious.” No one, in any case, proved willing to showcase it. Disappointed, he went back to working in the traces, once again focusing his attention full-time on developing the American Ballet School and company. After World War II—in which Kirstein served as a private and ended up being one of the Monuments Men who discovered the huge Nazi horde of stolen art buried in the Altaussee mine—the ballet company reconstituted as a unit connected to the City Center, the large mosque-like building on West 55th Street devoted to cultural events and offering low ticket prices. In its director, Morton Baum, Kirstein found a sympathetic soul, but City Center lacked the resources needed to guarantee the ballet an extended season, much less a permanent home. Still, by 1950, the American Ballet had achieved enough prominence and recognition for London’s prestigious Covent Garden to offer a five-week engagement. It proved enormously successful, and Kirstein, in a published article, brilliantly pinpointed why the company’s unique style—Balanchine’s style—had finally gained the recognition it deserved. His distinction lay, in Kirstein’s words, in “a leanness, a visual asceticism, a candor … and sometimes a galvanizing, acetylene brilliance, a deep potential of incalculable human strength.” What fascinated Balanchine, Kirstein wrote, “was the human body’s instinctive, yet scarcely unconscious, expression of its era—our corsetless, all but skirtless … era, where good social and theatrical manners are more a problem of individual obligation and affection than the reflection of the devotion for, or authority felt resident in, sovereign or system.” § Although homosexuality was omnipresent in the ballet world, it seems never to have been, in any explicit way, a point of contention between Kirstein and Balanchine, perhaps in part because Kirstein had married Paul Cadmus’ sister Fidelma in 1941. However, at no point before or after the marriage did he stop having sex with other men, sometimes becoming deeply attached to them. The dancer Pete Martinez, one of the great loves of Kirstein’s life in the late ’30s and early ’40s, not only lived with the Kirsteins for a time but became a close and trusted friend to Fidelma. Later, the painter and curator Jensen Yow would fill a similar role. Whether and to what extent Kirstein and Fidelma ever discussed these relationships (and others) remains unknown. Paul Cadmus was already dead when I began work on The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, but I talked at length with his long-term partner, Jon Anderson, who told me that Cadmus’ sense was that Fidelma understood early on that “Lincoln simply needed his close relationships with men—and that was that.” One could argue, if intent on categorization, that Kirstein might best be viewed as bisexual. He’d had affairs with women in his early twenties, including one of profound importance to him with the cultural doyenne Muriel Draper. That he cared deeply as well for Fidelma seemed “certain” to Jon Anderson, who felt that their relationship, at least during the early years of the marriage, definitely had a sexual component. As I wrote in my book, “the cynical conclusion would be that Lincoln married in order to foster his career. Yet that seems too cynical, given how little he would bother to cover up his homosexual activities—and how much he genuinely cared for Fidelma.” What seems nearly as certain is that to Balanchine homosexuality was simply incomprehensible—of no interest, and vaguely suspect. Distant and reserved by nature, Balanchine rarely discussed his or anybody else’s private life, yet of course he knew that male (not female) homosexuality was commonplace in the ballet world. We get an indirect clue to Balanchine’s attitude toward it in the figure of Vladimir Dimitriev, his most trusted adviser in the early years after his arrival in the U.S. Dimitriev proved a relentless advocate for Balanchine’s business interests, and he was no less outspoken (in a negative way) about Kirstein’s homosexual affairs. Early on, Kirstein became deeply infatuated with one of the school’s first students, Harry “Bosco” Dunham, a “small blonde from Ohio” in his early twenties who’d already had an affair with Paul Bowles (who warned Kirstein that Bosco was “nuts—that sitting down in a chair was drama to him”). Until Bosco came along, Kirstein had been so preoccupied with the multiple issues connected with putting the ballet on its feet that for a considerable period he’d been celibate. (As he wrote in his diary: “Streets full of sailors and marines. I keep my eyes neatly averted.”) But Kirstein found Bosco “wholly charming” and noted in his diary “the unmistakable solar plexus pains of strong attraction and longing which I have not felt since I can’t remember and which I thought up to now were forever dulled by jacking off and concentration.” Bosco responded in kind, but he proved wildly unpredictable and soon left the school and the city. (He would die in World War II.) But before that, while Bosco was still in attendance at the school, Dimitriev became aware that he and Kirstein were having an affair. Kirstein somehow discovered that Dimitriev was regularly opening his mail—including his lovesick letters to Bosco. Shocked, he confronted Dimitriev, who—instead of expressing apologies and regret—“made fun” of Kirstein’s predilections. “I can’t understand Americans,” Dimitriev boldly told him. “Were all Americans queer?” Yes, Kirstein angrily replied: “We are the nation of the great intermediates” (he’d been reading Havelock Ellis). Henceforth, he wrote in his diary, “no intimacy would be possible” with Dimitriev, and he would confine their interaction to “an efficient working school and business basis.” Soon thereafter, Kirstein noticed a tone of “slight contempt” from Balanchine when the two of them talked. Unlike Dimitriev, who was something of a bull in a china shop, Balanchine’s style was indirect, coolly dismissive. Yet the contempt was unmistakable, and it left Kirstein, as he confided to his diary, feeling “loose and worried” and prone to nightmares (in one: “Balanchine a murderer; myself shipwrecked. Disaster and guilt all around”). What’s more, Balanchine’s deprecatory attitude toward him carried over into their work together. He had expected a collaboration; what he got was an off-handed assignment to raise money and attend to the multiple small tasks of an administrative assistant. In one of the newly acquired letters, Kirstein poignantly reveals how deeply wounded he felt all of his adult life at Balanchine’s patronizing view of him—and Kirstein wasn’t a whiner and never indulged in self-pity. “Balanchine returned,” Kirstein wrote, “he is as cold as ice. … I can’t expect that his nature would change. … With me, it is no use; I neither interest or amuse him, and he has no basis upon which we can speak … it makes me feel sad that I can talk with all the other people with whom I work, and George seems to have no interest … the only thing he really loves is music … for this he has a passion, and it is wonderful and disinterested, but on the other things, he leaves me alone—with no trace of caring.” In all the long years that followed, the basic contours of the Kirstein-Balanchine relationship remained constant. An occasional business lunch or dinner aside, the two men never became friends, nor even socialized other than incidentally. Kirstein always retained his profound belief in Balanchine’s genius, and he devoted himself to creating the most ideal circumstances possible for its expression. His zeal did occasionally falter—the result of emotional exhaustion or the demands of his own multiple projects—but his central conviction of Balanchine’s unmatchable brilliance held steady. When Balanchine died in April 1983, Kirstein stepped in front of the curtain the following night and told a hushed audience, in a slightly trembling voice that Balanchine “is with Mozart, Tchaikovsky, and Stravinsky. I do want to tell you how much he valued this audience, this marvelous audience … you kept us going fifty years, and will another fifty. One thing he didn’t want was that this be interrupted. We will proceed.”

Martin Duberman’s latest book is titled Reaching Ninety. His forthcoming collection, The Line of Dissent, will be published by The G&LR.