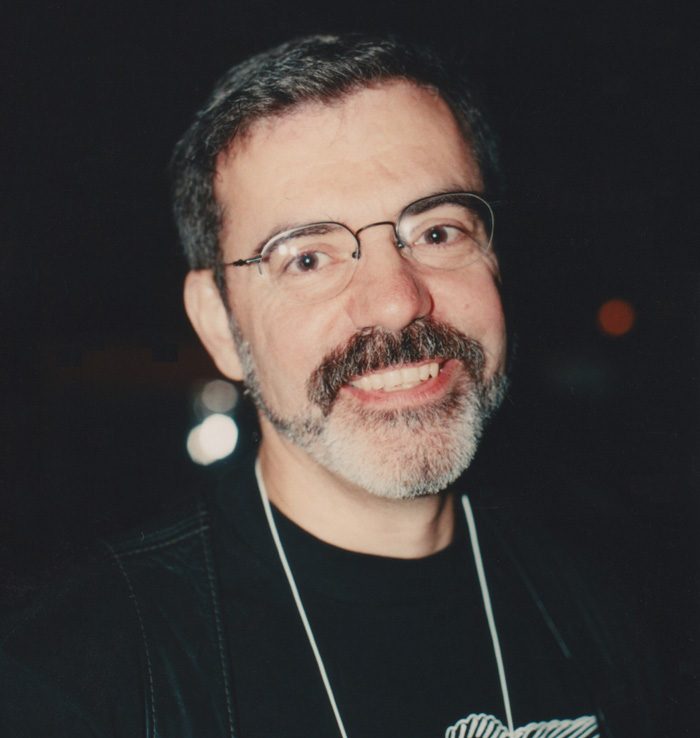

My Desire for History: Essays in Gay, Community, & Labor History

My Desire for History: Essays in Gay, Community, & Labor History

by Allan Bérubé

Edited by John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman

University of North Carolina Press

332 pages, $65. (paper $24.95)

WORLD WAR TWO—John Wayne’s war, my father’s war. Gay men and lesbians were there too. For many, in fact, the war was their great coming-out opportunity, as men and women were moved from their farms and small towns to the coastal cities, into same-sex environments where they discovered each other and their own desires. The war also encapsulated society’s ambivalent attitude: tolerate the lesbians and gays when their numbers were needed, then purge them ruthlessly when the war is over.

This connection—that we can claim a share in America’s “greatest generation,” that “their” history is our history, too—was Allan Bérubé’s outstanding contribution to gay and lesbian studies, primarily in his 1990 book Coming Out Under Fire. Bérubé (1946–2007) won wide acclaim for the book, and even received a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1996. He was working on what would have been another significant connection—a gay presence in labor history—when he died suddenly from ruptured stomach ulcers at age 61.

This volume is a collection of Bérubé’s essays, lovingly assembled by Estelle B. Freedman and John D’Emilio, historians themselves, and friends and colleagues of Bérubé’s. Although the essays are not in strict chronological order, when read from start to finish they suggest the narrative arc and even the drama of Bérubé’s own intellectual development as he went, in the editors’ words, “from a working-class, Franco-American youth growing up in a New Jersey trailer park to an influential historian and public intellectual.” Be sure to start with the editors’ long introduction, which gives the details of Bérubé’s life story.

The first essays show Bérubé’s initial interest in gay and lesbian history and were often written in reaction to specific political events. In 1980, when CBS aired a news special that hyperventilated over the alleged gay domination of San Francisco politics, Bérubé responded with an essay about parallels to the 1959 mayoral election, where the challenger denounced “a city admittedly overrun by deviates.” When officials moved to close the San Francisco bathhouses out of fear of AIDS, Bérubé described in another essay how a similar campaign had been waged against Chinese institutions earlier in the century. His goal as a community historian was to use the past to give context to the present. Some of these essays were originally the scripts to slide-shows that Bérubé gave to various audiences, a medium that seems exceptionally fitting for a community historian.

As he explored California’s gay history, Bérubé discovered his first great topic: the lesbian and gay presence in World War II. The essays collected here were published before Coming Out Under Fire and function as a kind of preview to the book, full of the rich anecdotes that form the heart of Bérubé’s research. There’s the 21-year-old naval officer who in 1944 walked into the bar of the Biltmore Hotel in San Francisco and realized what was going on: “It was there I learned that there could be a camaraderie, that people who initially had nothing but their homosexuality in common could get together and like one another and talk. … I’m sure that thousands of men had the same experience that I did—discovering that there is a gay society.” You can feel the birth of the gay rights movement right there in his words. There’s the man whose lover was killed in the Philippines: “I was treated with such kindness by the guys I worked with, who all were totally aware of why I was hysterical. … One guy in the tent came up to me and said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were gay? You could have talked to me.’ This big, straight, macho guy. There was a sort of compassion then.” Of course, there were also witch hunts and purges, and Bérubé tells the tragedies as well.

One particularly engaging story has both highs and lows. In 1943, a group of gay men stationed in South Carolina wanted a way to keep up with all the other gay men they had met at other bases. So they started “The Myrtle Beach Bitch,” a mimeographed newsletter: “We mentioned ‘Ray’ that we’d met in Mississippi, and we wrote ‘Miss Ray,’ or ‘Martha Ray,’ or whatever we called her. ‘That bitch is out doing Clovis, New Mexico.’” There’s an infectious giddiness as these men describe their exploits to Bérubé forty years later. There were only ten copies of each issue, but they circulated widely. That was enough to get them locked up: “I felt very humiliated. Yet I don’t think I was ever gayer! I must have made more wisecracks in that stockade and had more fun. Kate would scream out, ‘Oh, shut up Woodesia!” She called me Woodesia [his nickname was Woodie]and I called her Kate. You see, we kept it up! Fuck ’em! We were going to be discharged.” And they were, dishonorably, without pay or rights.

The essays in the middle of the collection become both more personal and more abstract, as Bérubé tries to locate the particulars of his own life—specifically, class and race—within a larger theoretical structure. Here he wrestles with important topics. Unfortunately, in my opinion, the topics win, as he tells relevant anecdotes but can’t quite get at their meaning. The essays on class arise out of his own anxieties about his blue-collar, Franco-American origins and his middle-class status as a historian—anxieties about not passing for middle-class, or about passing too well and thereby abandoning his working-class roots. “How Gay Stays White and What Kind of White It Stays” probes one of the sorest spots in the gay movement, and does so unsparingly. At its end, Bérubé admits that his questioning “is not headed toward innocence or winning or becoming not white or finally getting it right. I don’t know where it leads, but I have some hopes and desires.”

The collection closes with essays from Bérubé’s final research project, a history of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union (MCSU), a small West Coast union that was multiracial and gay-friendly—a successful merging of class, race, and sexuality. In these essays, you see him struggling to find a style for telling a story that meant so much to him. He tries to filter it through his own class-based experience; he experiments with an impressionistic style. In the end, he never produced a full-length book. Instead, he went back to his earlier medium, the slide show, whose long script ends the collection.

The stewards on luxury cruise liners performed the domestic chores: housekeeping, waiting, and such. Because some lines refused to hire women or blacks, the “women’s” or “colored’” work was left to gay men, so much so that the liners were called “fruit boats.” Although the MCSU was founded in 1901 to exclude Asian workers from the ships, by the 1930’s it had become more radicalized. It opened its membership to black workers, both men and women, and Communists also joined the ranks. As the union’s enemies attacked, the union responded with solidarity: “If you let them red-bait, they’ll race-bait, and if you let them race-bait, they’ll queen-bait. These are all connected. That’s why we have to stick together.” But in the 1950’s, its enemies proved too strong, and the era’s anti-Communist forces destroyed the union.

One of the gay men in the MCSU, Mickey Blair, summed up what knowing the history of the union means for anyone who, in Bérubé’s words, “dreams about militant unions with visible gay leadership that are dedicated to racial equality, economic justice, and solidarity across many lines.” As Blair told Bérubé, “We proved that it could be done so it’s not just a dream. We can do it again, only differently this time.” This is what Bérubé himself was looking for in the history he researched, as he states in the passage from which the editors have taken the title for this collection: “I’ve begun to realize that my desire for history comes from a painful, dislocated place inside me. … By searching for a past when people pulled together to fight such threats despite their differences, then pulling that experience back with me into the present, I think I’ve been trying to rebuild a sense of myself that’s not isolated, that’s instead connected to a multi-faceted, cross-generational ‘we’ made so strong it can’t be destroyed by the destructive forces that have torn my own life apart.” His desire to be our community’s historian gives life to this collection.

Michael Schwartz, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in Boston.