AS THE 2013 CENTENARY of William Inge’s birth approaches, his plays continue to be produced even as some critics consider his work creaky, dated, and beyond resuscitation. In 2008, there was a Broadway production of Come Back, Little Sheba with S. Epatha Merkerson, Tony Award-nominated for the lead role, never before played by an African-American. In 2009, two-dozen unproduced plays were found in a Kansas college library that generated new interest, including a staged reading with Sigourney Weaver of Off the Main Road, one of the discovered plays.

To state my contention as boldly as possible at the outset: William Inge was homosexual but was never reconciled to his sexual orientation. He held out the possibility of a “cure,” submitting to several psychoanalysts, notably Lawrence Kubie, whose specialty was gay artists and writers. Inge even referred his lifelong friend Tennessee Williams to Kubie.* Inge biographer Ralph F. Voss remarked in A Life of William Inge (1989): “He was a playwright of repression.” Warren Beatty, who made his Tony-nominated Broadway debut in Inge’s A Loss of Roses in 1959 and his film debut in Splendor in the Grass in 1961, observed that “Bill Inge understood the inhibitions of Middle America better than anyone.”

Inge never wrote anything about being gay, though his later works—such as the one-act unproduced play “Boy in the Basement” and the screenplay for Bus Riley Is Back in Town (1965), written under the pseudonym William Gage—had gay male characters, albeit repressed ones. John M. Clum wrote in Acting Gay: Male Homosexuality in Modern Drama (1992) that several of the later works in Eleven Short Plays “seem to be closet dramas in more ways than one … dramatizations of shattering invasions of the secret life of lonely homosexual men. They are also symptomatic of Inge’s difficulty in tying his homosexuality to received definitions of manhood.”

There are indications in several late one-act plays and a scene in one film that hint at Inge’s loneliness and despair as a gay man. Vito Russo wrote in The Celluloid Closet (1981): “On the American screen the discovery of a character’s homosexuality came most often as  the shock of seeing the familiar turn alien, a ploy of classic horror films, like studying a pretty picture and watching it turn into a grinning skull. Revelation scenes abounded. Bus Riley Is Back in Town … contains this kind of lurking, sex-defined creature.” Russo’s reference is to Spencer, a lecherous old mortician, who puts his hand on the knee of an all-American sailor boy, trying to entice him to move into his place by offering to send him to mortician’s school. Spencer pleads, “I want you here with me. … I’m a lonely man.” The sailor flees when he sees the “demon” in the mortician’s face. The lonely and lecherous mortician prototype reappears in “Boy in the Basement,” which has a denouement that could be considered both pederastic and necrophiliac. Michael C. Hall’s repressed gay undertaker in HBO’s Six Feet Under seems an updated post-Stonewall reprise, equating same-sex eroticism with a death force.

the shock of seeing the familiar turn alien, a ploy of classic horror films, like studying a pretty picture and watching it turn into a grinning skull. Revelation scenes abounded. Bus Riley Is Back in Town … contains this kind of lurking, sex-defined creature.” Russo’s reference is to Spencer, a lecherous old mortician, who puts his hand on the knee of an all-American sailor boy, trying to entice him to move into his place by offering to send him to mortician’s school. Spencer pleads, “I want you here with me. … I’m a lonely man.” The sailor flees when he sees the “demon” in the mortician’s face. The lonely and lecherous mortician prototype reappears in “Boy in the Basement,” which has a denouement that could be considered both pederastic and necrophiliac. Michael C. Hall’s repressed gay undertaker in HBO’s Six Feet Under seems an updated post-Stonewall reprise, equating same-sex eroticism with a death force.

Despite Inge’s repressed same-sex feelings, a persistent consciousness about gender and sexuality emerges in all his writing. Jeff Johnson wrote in William Inge and the Subversion of Gender (2005) that Inge engaged in a process of a “subversive manipulation of stereotypes for the purpose of intentionally undermining expected gender roles and thereby destabilizing social norms.” Furthermore, Inge’s work foreshadowed the transformation of American institutions, communities, and the nuclear family that would come a decade later with the second wave of feminism and the gay rights movement.

William Inge and Tennessee Williams became enduring friends despite a rivalry that lasted a lifetime. They met in 1944, in St. Louis, where Inge was the drama critic for the St. Louis Star-Times. He interviewed Williams, who was suffering from “the shock of sudden fame” after his first success with The Glass Menagerie. Gore Vidal wrote in Palimpsest that they “had a brief affair,” something not referenced by Williams in either his Memoirs, his Notebooks, or in New Selected Essays: Where I Live. Williams’ reputation is indisputably more substantial today than Inge’s, but in the 1950’s Inge had four major Broadway productions—Come Back, Little Sheba (1950), Picnic (1953), Bus Stop (1955), and The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (1957)—all of which were translated to film.

In 1973, at age sixty, Inge committed suicide by carbon monoxide inhalation while sitting in a Mercedes in the garage of his Hollywood Hills home. Regardless of any rivalry or competition, Williams remained abidingly loyal to Inge, praising him in New Selected Essays: Where I Live: “And that’s when and where you meet the talent of William Inge, the true and wonderful talent which is for offering, first, the genial surface of common American life, and then not ripping but quietly dropping the veil that keeps you from seeing yourself as you are.” And in Memoirs Williams wrote: “his works were suffused with the light of humanity at its best.”

Come Back, Little Sheba

When Come Back, Little Sheba opened on Broadway, it was praised by Brooks Atkinson, the powerful New York Times critic, as “terrifyingly true … with a kind of relentless frankness and compassion that are deeply affecting.” Shirley Booth won a Tony Award and an Oscar for the 1952 film version, and stage costar Sidney Blackmer also got a Tony (for the role that Burt Lancaster played in the film).

Come Back, Little Sheba is about the grindingly unhappy marriage of Lola and Doc Delaney. Lola, once the “beauty queen of the senior class,” became pregnant on her first date with Delaney; the baby died during childbirth, a loss from which she has never recovered. (The beauty queen archetype is revisited in Picnic in the character of Madge, who laments, “It’s no good just to be pretty. It’s no good.”) Delaney is an emotionally remote recovering alcoholic who laments a shotgun marriage and the stifling of his aspiration to be a physician before he settled on being a chiropractor. Lola and Doc face a crisis when art student Marie, an attractive young boarder, and Turk, a studly frat-boy and male model, enter their lives. Tensions between the couple reach a boiling point when they realize feelings of sexual longing that become articulated in the following exchange.

Lola: You watch young people make love in the movies, don’t you, Doc? There’s nothing wrong with that. … Why shouldn’t I watch them? But, he’s just posing for her. Lots of the athletes do it.

Doc: You like that fellow Turk. You said so. And I say he’s no good. Marie’s sweet and innocent; she doesn’t understand guys like him. I think I oughta run him outa the house.

In another scene, Delaney escapes to the bathroom to covertly sniff Marie’s lilac-scented bath powders, and Lola comments on the art student sketching her model.

Lola: You mean … he’s gonna pose naked?

Marie. No. The women do, but the men are always more proper. Turk’s going to pose in his track suit.

Lola: The women pose naked, but the men don’t. If it’s all right for a woman, it oughta be for a man.

Lola is clearly aroused as she voyeuristically inquires about Marie and Turk. Inge’s stage direction has Lola peering at Turk “so closely, he becomes a little self-conscious and breaks pose.” Turk is repulsed by Lola’s scrutiny: “Hey, can’t ya keep her outa here? She makes me feel naked. … Didn’t she ever see a man before?”

For the early 1950’s, Come Back, Little Sheba addressed controversial subjects such as premarital sexuality, out-of-wedlock pregnancy, and alcoholism. The film contains sexual fantasies and fetishism and the eroticization of the male body with blatant phallic symbolism. There’s an explicit seventeen-minute out-of-control scene about alcoholism in which Doc attempts to strangle Lola. (Choking re-emerges in a sexual power-domination scene in Splendor in the Grass.) During the 1950’s, premarital sex was categorically condemned and typically portrayed as impersonal, selfish, pregnancy-inducing, and fraught with disease.

Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953) reported that 68 percent of males and fifty percent of females had experienced coitus by age eighteen. His research also showed that 37 percent of adult males and thirteen percent of females had at least one homosexual experience since puberty. The reports are referenced in the following dialogue:

Turk: Have you read the Kinsey report, Miss Buckholder?

Marie: I should say not.

Turk: How old were you when you had your first affair, Miss Buckholder?—and did you ever have relations with your grandfather?

The publication of the two reports was momentous, and Inge knew it, having focused on the identical issues of sexuality in Come Back, Little Sheba.

Picnic

Inge won a Pulitzer Prize for the play Picnic and Joshua Logan an Oscar in his directing debut for the 1955 film version. Hal, played by William Holden in the movie, is a drifter with no money who arrives in Elgin, Kansas, looking for his college friend, Alan Benson, whom he plans to ask for a job. Hal meets the town beauty queen Madge, played by Kim Novak, and sparks fly. As it turns out, Alan is interested in Madge and becomes jealous of Hal, accusing him of stealing his car and his girlfriend. Hal leaves town to escape the police, pleading with Madge to join him. Following the advice of her younger tomboy sister and her heart, Madge decides to leave Elgin.

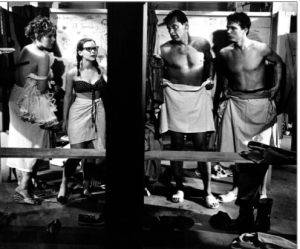

Holden was the object of desire in Picnic and managed even to trump the beautiful Novak, who was described by critic Dave Kehr as “elusive and ethereal at one moment … thrillingly carnal the next.” In a chapter called “Age of the Chest” in a 1997 book called Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties, author Steven Cohan writes: “Logan’s camera subjects the star to a steady gaze, placing Holden in the position of exhibitionist and focusing on his body with the kind of unrelenting visual interest supposedly reserved only for a female star like Novak.” Joshua Logan understood the commercial potential of an audience’s voyeuristic attraction to the male body, and Holden’s sculpted chest became the focal point on a Cinemascopic wide screen at Radio City Music Hall. What’s more, Hal is well aware of his own irresistibility, declaring: “I was hitchhiking my way down to Texas on this big oil deal when two babes pull up in this big yellow convertible and one of them slams on the brake and hollers, ‘Hey beefcake! Get in.’ So, I get in.”

Several characters succumb to Holden’s appeal as the “object of the gaze.”* This presentation of the male body as a passive erotic object for the gaze of female spectators inverts the usual objectification of women by (heterosexual) men. Hal’s erotic potential is also revealed in the following dialog, in which he’s encouraged to bare his chest.

Mrs. Potts: You’ll be awfully hot in that jacket. You better take it off.

Hal: Do you think anybody would mind?

Mrs. Potts: Naw. What’s the difference? You’re a man.

In another scene, Hal’s shirt is literarily torn off by a woman, Rosemary, who explains: “You remind me of one of those old statues. One of those Roman gladiators. All they had on was a shield. My, those ancient people were depraved.” At this point Rosemary, a stereotypical schoolteacher, unmarried and sexually frustrated, proceeds to shred his shirt.

Author R. Barton Palmer recognized this male bodice-ripping as overturning gender expectations, writing: “Oh my goodness, a bodice-ripper! It’s the same kind of iconography that one would associate with that particular form of the popular romance. … It’s not the woman’s bodice that’s ripped. It’s the man’s bodice that’s ripped.”

Bus Stop

Bus Stop (1956), also directed by Joshua Logan, was translated to film as a star vehicle for Marilyn Monroe by abridging the play’s multiple narratives to focus on the relationship between Cherie (Monroe), a disillusioned saloon singer, and Bo Decker (Don Murray in his film debut), a boisterous, simple-minded, chauvinistic cowboy. Cherie aspires to be a chanteuse, and she carries a map with a red line that leads from River Gulch, her hometown in the Ozarks, directly to Hollywood. As in Picnic and later in Splendor in the Grass, Inge’s protagonists must make a geographic change, leaving home in order to be free of its stifling constraints.

The overconfident and naïve Bo has left his Montana ranch for only the second time in his life to participate in the big rodeo in Phoenix. He’s accompanied by Virgil Blessing, a mentor who’s guided him most of his life, with whom he exchanges the following curious bit of dialogue:

Bo: What’s the difference between a physical attraction and a regular attraction?

Virgil: Gals can be attracted to a fella for lots of reasons. His mind.

Bo: His mind!?

Inge wrote that Bus Stop was “a composite picture of varying kinds of love. … The cowboy’s eagerness, awkwardness, and naïveté were interesting only when seen by comparison, in the same setting with the amorality, the depravity, the casual earthiness, the innocence, or the defeat of the other characters.” Virgil tells Bo why he never married. “It was cowardly of me, I s’pose, but ev’ry time I’d get back from courtin’ her, and come back to the bunkhouse where my buddies was sittin’ around talkin’, or playin’ cards, or listenin’ to music, I’d jest relax and feel m’self so much at home, I din wanta give it up.” This description of the intimate relationship between cowboys predates Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain (1997) by more than four decades.

Splendor in the Grass

Inge won an Oscar for the screenplay of Splendor in the Grass; Natalie Wood was nominated for best actress; and Elia Kazan directed the film. In an interview (Elia Kazan: Interviews), Kazan suggested that the film, which takes place in pre-Depression Kansas, depicted the parallelism between the collapse of an old moral order and the disintegration of an economic system. Indeed, Splendor in the Grass contains the thematic array familiar to Inge’s work: moral disorder and its consequences; mental illness and institutionalization along with the curative authority of psychiatry. Two high-school teenagers, Deanie (played by Natalie Wood) and Bud (played by Warren Beatty) fall in love; they’re terrified by their physical passions and are both driven to mental and physical illness. Following an attempted suicide, Deanie suffers a mental breakdown and is hospitalized in a Menninger-like clinic for more than a year. Bud collapses with pneumonia in the following scene, pleading for advice from his doctor.

Bud: I can’t start seeing her again, Doc, and go back to things the way they were, taking her out every night, holding her close … kissing and … then going home, feeling kinda empty and … a guy can go nuts that way.

Dr. Smiley: Come in Friday and I’ll give you another sun lamp treatment and a shot of iron.

Bud’s promiscuous sister Ginny dies in an automobile accident, and his father, whose oil holdings were wiped out by the 1929 stock market crash, commits suicide.

Kazan’s direction, as with Logan’s, explores modern masculinity by sexualizing leading men, often underwater, making water sensually erotic or simply exploiting the opportunity to present bare chests, such as those of William Holden and Cliff Robertson showering together in Picnic; Don Murray’s submerged in a tub in Bus Stop; or Warren Beatty’s in Splendor in the Grass, showering with his entire basketball team and bare-chested under a waterfall in a rape scene.

Regrettably, Inge portrays women as obnoxious enforcers of sexist values, spying on their neighbors as if perversity lurked behind every picket fence. However, he also exposes the evils of brutal masculine authority and the realities of coercive sexuality, as in the following curious scene of sexual submission:

Bud: Down on your knees, I say!

Deanie: Bud, you’re hurting me.

Bud: Now admit it … Tell me you love me. Tell me you can’t live without me. Admit it … You’re nuts about me aren’t you? … At my feet, slave.

The film concludes with Deanie’s awakening, as expressed in the following comment: “I’d always worshipped Bud like he was a god. But all this time he’s been a man, hasn’t he? Like other men all over the world, trying to get along.”

In Unfinished Show Business: Broadway Musicals as Works-in-Progress (2005), Bruce Kirle wrote: “From approximately 1963 onward, publications such as the New York Times and Time, mainstream critics such as Robert Brustein, and authors such as Philip Roth outed closeted gay writers on Broadway, who, in their opinion, were not qualified to write about heterosexual relationships or marriage.” Indeed, there are numerous examples of homophobic theatrical criticism during the 1960’s. For example, Richard Schechner wrote this in the Tulane Drama Review: “Albee makes dishonesty a virtue. We must not ignore what Albee represents and portends, either for our theatre or for our society. The lie of his work is the lie of our theatre and the lie of America. The lie of decadence must be fought.” Howard Taubman in The New York Times: “Very little of [Inge’s Natural Affection] seems natural … much is either sordid or shocking.” Stanley Kauffmann, also in the Times: “I do not argue for increased homosexual influence in our theater. It is precisely because I, like many others, am aware of disguised homosexual influence that I raise the matter.”

Most attribute Inge’s suicide to a failing career. There was no note, so we’ll never know how much his sexual orientation may have contributed to his suicide. It has always been a characteristic of the excluded and marginalized to express their experience in semi-autobiographical works. We have some clues that Inge struggled to present a counter-image through the despair of internalized homophobia, against the constraints of a heterosexist culture, but we’ll never know what variety of forms this might have taken had he lived a longer life.

* That Williams visited Kubie was confirmed by Gore Vidal in a 1985 review (“Immortal Bird”) of two books on Williams: “He even went to an analyst who ordered him to give up both writing and sex so that he could be transformed into a good-team player. Happily, the Bird’s anarchy triumphed over the analyst.”

Steven F. Dansky, activist, writer, and photographer for over fifty years, is the author of Hot August Night/1970: The Forgotten LGBT Riot (Christopher Street Press).

Discussion1 Comment

Logan didn’t win an Oscar for Picnic, Delbert Mann won that year for ‘Marty’.