Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India

Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India

by Joseph Lelyveld

Knopf. 448 pages, $28.95

Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention

Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention

by Manning Marable

Viking. 608 pages, $30.

TWO MAJOR BIOGRAPHIES about larger-than-life 20th-century political figures were published this year, Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India, by Joseph Lelyveld, and Malcolm X, by Manning Marable. The subjects of the books share a common destiny, although not contemporaneously, as victims of assassination, and both became global legends dedicated to the struggle for human rights on different continents—Gandhi for Indian independence from British colonial rule, and Malcolm X for ending white supremacy in the United States. These books chronicle the complex metamorphosis of both political leaders from humble beginnings characterized by victimization and oppression into audacious players at the forefront of revolutions that affected the future of millions. Pulitzer Prize-winning Lelyveld, a former executive editor of The New York Times, and Marable (who died a few days before his ten-years-in-the-making book was published), a leading scholar of black history and professor at Columbia University, bring into question same-sex-related experience, behavior, and desire by the subjects of their biographies.

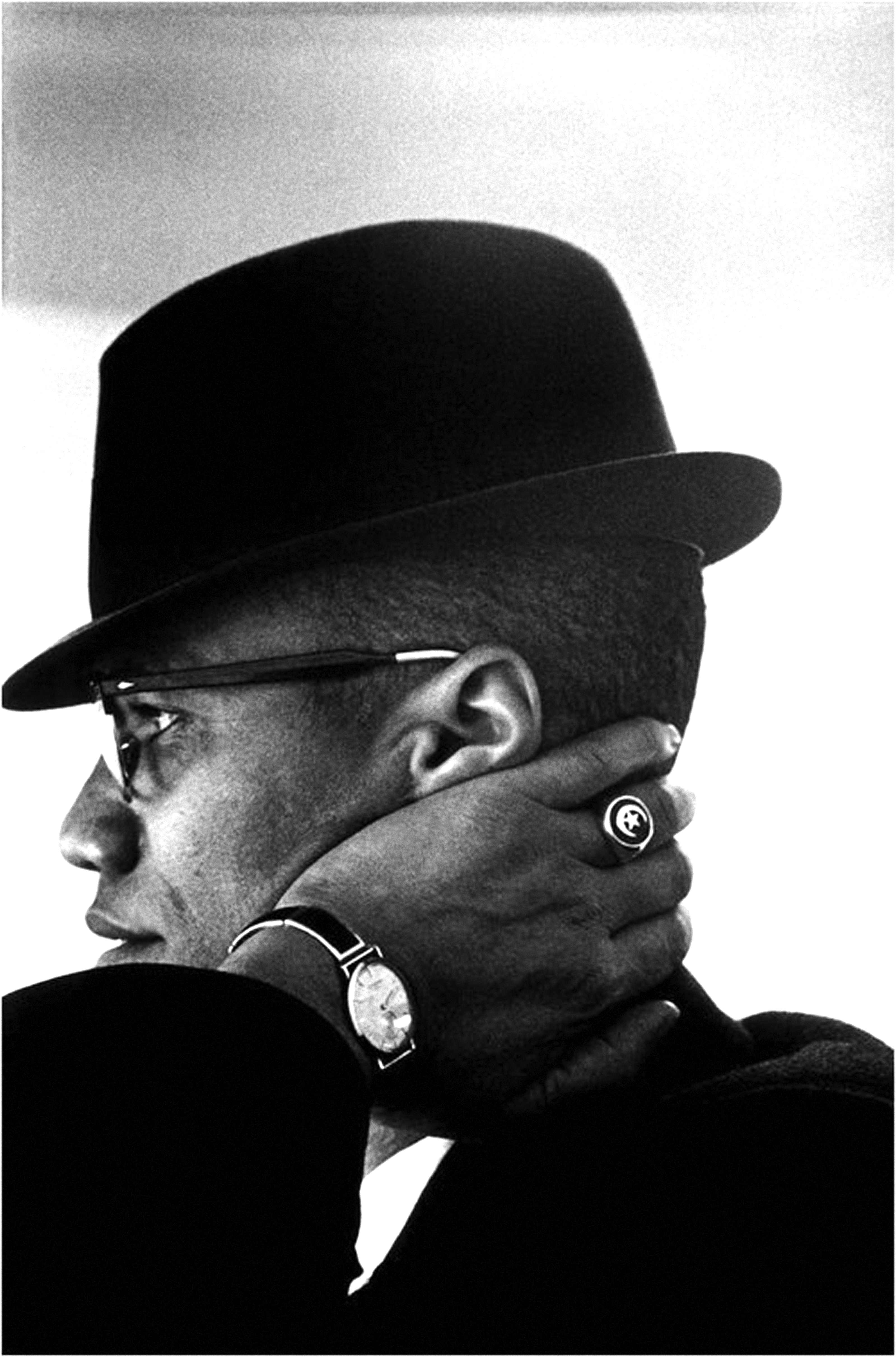

Gandhi and Malcolm X were consciously aware of their legacies and the historicizing function of narrative, and as much as possible they exerted control over any accounts of their lives, believing their biographies to be the embodiment of politics, social history, and human destiny. The national symbolism is embodied in their physical presence: Gandhi rejected the Western-style suit in favor of the hand-woven khadi costume of an Indian peasant; and Malcolm X abandoned conked hair and the zoot suit for the Nation of Islam’s basic blue-serge suit. Each was captured iconically by a well-known female photographer: Gandhi by Margaret Bourke-White for Life magazine (Figure 1); Malcolm X by Eve Arnold for Magnum Photos (Figure 2). Both wrote classic autobiographies—Gandhi’s An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1927-28) and The Autobiography of Malcolm X (with Alex Haley, 1965)—and each seized the historical moment through a transformative life history. Malcolm X’s autobiography falls within the literary genre of prison narrative; he joins a familiar tradition—exemplified by Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, in which he wrote that “prison life with its endless privations and restrictions makes one rebellious,” as well as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail—which recognizes the symbolic role of imprisonment as the cauldron for rebellion against the absolute power of the state. Malcolm X was imprisoned from 1946 to 1952 and Gandhi intermittently, serving two years of a six-year sentence for sedition from 1922 to 1924.