Just Kids Limited Edition

Just Kids Limited Edition

by Patti Smith

Ecco. 304 pages, $27.

PATTI SMITH’S Just Kids is a memoir about the singer’s relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989). The book resonates with all the portentousness of the Fates spinning threads around inextricably entangled mortals. Just Kids isn’t a lurid exposé but a serious reflection upon creative vision, regeneration, and devotion.

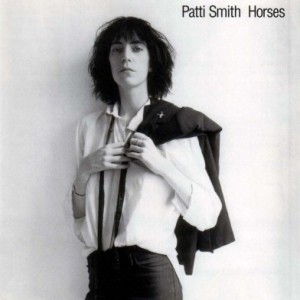

The memoir is a meditation on the shared journey of Smith and Mapplethorpe on the way to becoming artists. When they met in Brooklyn in the late 1960’s while in their early twenties, they were experimenting in different media and didn’t know where they’d end up. They were longing for something undefined. He strung African trade beads, feathers, and rabbit’s feet into necklaces, experimenting with collages and installations. She doodled accounts of their daily life in journals, which later evolved into poems and lyrics. Always confident “that the Fates were conspiring to help their enthusiastic children,” Smith became the legendary poet and punk rocker who was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2007. Her debut album Horses, featuring Mapplethorpe’s now iconic photograph of her on the cover, made Rolling Stone’s list of 500 greatest albums. Mapplethorpe would become one the most controversial artists of the late 20th century, giving rise to the first trial of a gallery for the art it displayed in U.S. history.

About their meteoric rise to prominence, Smith observes: “Life is an adventure of our own design, intersected by fate, and a series of lucky and unlucky accidents. I had in mind to become an artist and poet, and through that pursuit I found the root of my voice.” Just Kids is a memoir that evokes an era when subcultural renegades migrated to New York and became the romanticized celebrities of urban legend. When they moved into the Oz-like Hotel Chelsea, they encountered fellow residents who were some of the foremost creative figures of that time—William Burroughs, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Andy Warhol, to name a few.

The dreamlike Just Kids belongs to a subgenre comprising other works that portray the complexities of relationships between women and gay men. In “The Coral Sea,” Smith’s elegiac tribute to Mapplethorpe, she describes their meeting and his death. “The first time I saw Robert he was sleeping. I stood over him, this boy of twenty, who sensing my presence opened his eyes and smiled. With few words he became my friend, my compeer, my beloved adventure. … But as I was leaving something stopped me and I went back to his room. He was sleeping. I stood over him, a dying man, who sensing my presence opened his eyes and smiled.”

In Patricia Morrisroe’s 1995 biography of Mapplethorpe, a fellow Pratt student remembered: “They began trading clothes; friends were struck by their physical similarity to each other. It was difficult to tell where Robert began and Patti left off. Together, they exuded all kinds of sexual possibilities.” Of the 1978 short film Still Moving, directed by Mapplethorpe in collaboration with Smith, René Ricard wrote in Art in America: “Their friendship is their masterpiece. … What’s on show, the works, is documentation or artifact; its importance is that it was made by these people. This works doubly. Mapplethorpe photos are always beautiful, but a Mapplethorpe photo of Patti Smith is, well, history.”

Sylvia Wolf, adjunct curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, discovered three-ring binders with hundreds of small black-and-white Polaroid photographs protected within archival plastic sleeves in the archives of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. King went on to curate an exhibit of her discovery at the Whitney along with a catalog (Mapplethorpe: Polaroids, 2007), where she described the pictures as “personal, intimate, spontaneous, and delightful.” These photographs confirm Smith’s account of Mapplethorpe’s creative development, offering insight into his artistic process and subsequent entry into the landscape of taboo and transgression. It begins with a casual encounter with, and subsequent borrowing of, a Polaroid camera. Smith was Mapplethorpe’s first model and he was his own first male subject.

Prior to Mapplethorpe’s transition into photography, he was spellbound by images in male magazines and used them in his installations. Smith recalls that he was working on an installation and completely covered a stretched canvas “with outtakes from his male magazines. The faces and torsos of young men wrapped the frame.” The Polaroids attest to the lasting impact of gay pornography on the photographer’s development. Mapplethorpe believed that his photographs formalized porn in a way that had never been done before, that his images transcended the uncomplicated documentation of sexuality. He made “beautiful photographs with pornographic material” such that the images became “magical.”

Mapplethorpe’s artistic evolution coincided with a personal journey toward understanding his sexual identity. Smith seems incapable of interpreting his sexuality, writing: “My reaction to his admission was more emotional than I had anticipated. Nothing in my experience had prepared me for this. … He had never given me any indication in his behavior that I would have interpreted as homosexual.” Puzzled by his sexuality, she reports: “I just looked at him, not understanding at all. There was nothing in our relationship that had prepared me for such a revelation. All of the signs that he had obliquely imparted I had interpreted as the evolution of his art. Not of his self.” She asked him what “drove him to take such pictures.” He answered: “Someone had to do it, and it might as well be him.” She believed “he had a privileged position for seeing acts of extreme consensual sex and his subjects trusted him. His mission was not to reveal, but to document an aspect of sexuality as art, as it had never been done before. What excited Robert the most as an artist was to produce something that no one else had done.”

Mapplethorpe was fascinated by Times Square, which he called “the Garden of Perversion.” Upon seeing the film Midnight Cowboy (which he called a masterpiece) and identifying with its hustler hero, he started to mingle with New York’s “cons, pimps, and prostitutes,” announcing: “Hustler-hustler-hustler. I guess that’s what I’m about.” He loved the nightlife, which supplied him with subjects to photograph, gave him an adrenaline rush, and satisfied his quest for the unexpected. “I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before. … I see things like they’ve never been seen before. Art is an accurate statement of the time in which it is made.” In Smith’s analysis, “Robert was cutting out sideshow freaks from an oversized paperback on Tod Browning. Hermaphrodites, pinheads, and Siamese twins were scattered everywhere. It threw me, for I couldn’t see a connection between these images and Robert’s recent preoccupation with magic and religion.” Tod Browning’s 1931 cult-classic film Freaks profoundly influenced Mapplethorpe, as it did fellow photographer Diane Arbus, who claimed that “there’s a quality of legend about freaks. … They’re aristocrats.”

Mapplethorpe’s œuvre generated so much controversy and publicity that he once grumbled: “I just want to be written about as a normal artist.” Kobena Mercer, cultural worker and critic, thought that Mapplethorpe æstheticized his subjects “to the abject status of thinghood.” Jack Fritscher in Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera (1994) wrote that “Robert attempted to stake out a fetish franchise of white leather and black men.” Edmund White attempted to contextualize Mapplethorpe’s vision thus: “[When he] looks at black men, he sees them in two of the few modes of regard available to white America today: he sees them either æsthetically or erotically.”

In Just Kids, Smith sidesteps criticisms that Mapplethorpe objectified and exploited subjects, proposing that he adhered to a “law of empathy.” He could project his personality onto his subject and, “by his will, transfer himself into an object or a work of art, and thus influence the outer world.” Mapplethorpe didn’t agree that he objectified his black male subjects. He said in the Paul Tschinkel film Robert Mapplethorpe: “It’s like bronzes. … I often say photographing black men is like photographing bronzes. In other words, a bronze is a certain color for a reason. Somehow the definition of musculature is subtler. … That is sculpture to me. And that’s one of the points I’m making in photography is being a sculptor without actually having to spend all the time, sort of modeling with your hands. That’s much too archaic, for me. I think you can capture with photography what is really sculpture.”

Since Mapplethorpe’s death, cultural arbiters have generally rejected categorization of his work as subcultural fetishism and deflected charges of sexual objectification and racial exploitation. The Guggenheim Hermitage Museum exhibition “Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition” (2006) associated his approach to the human figure with classical art and 16th-century Mannerism. The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation donated three photographs to Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, including a 1980 self-portrait of the photographer wearing lipstick and a feather boa that will be displayed in the self-portraits collection in the company of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Dürer, Ingres, and Reynolds, among others.

Mapplethorpe lamented: “I just hope I can live long enough to see the fame.” Alas, most of his fame has come posthumously. Surely no other photographer in history has been written about and analyzed as much. He will be forever associated with same-sex eroticism and inextricably linked to the AIDS epidemic, as personified in his final, spectral self-portraits of 1988. Doubtless his startling and subversive images will continue to generate controversy as long as there’s an “us” and a “them.”

As for Patti Smith, since the publication of Just Kids, she has re-emerged as a cultural legend of the 70’s and 80’s whose art serves as a musical counterpart to Mapplethorpe’s photography. She is immortalized not only by her own work but by the photographer’s ascetic black-and-white images of the godmother of punk.

Steven F. Dansky’s one-person photography exhibit, “In Public: Studies from the Street,” was shown in Las Vegas during summer 2010.