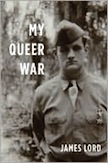

My Queer War

My Queer War

by James Lord

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

352 pages, $27.

IN PARIS, while serving with the U.S. military during WWII, James Lord found his way to an address on the rue des Grands Augustins and informed the secretary who opened the door that he had come to see Pablo Picasso. He had no appointment, but Lord’s uniform provided bona fides; Americans had just expelled the Nazis (Lord amusingly points out that it didn’t take long for some Parisians to resent that favor).

The soldier and the artist hit it off, and Lord became a regular at Picasso’s 11 a.m. studio receptions. Some months after their first meeting, according to Lord, Picasso made a pronouncement. He took Lord by the shoulders, pivoted him to face the other guests, and said, “Here is my young friend Lord. Look at him closely. Someday he will surprise us. There will be great things in his future. He will do something to astonish us someday.”

Lord went on to have a distinguished career as a journalist, memoirist, and biographer. But nothing in his oeuvre seems quite to have fulfilled Picasso’s expectation. That is, until now. My Queer War, a memoir of Lord’s youthful military days, is indeed astonishing. It’s a shame that Picasso isn’t around to savor it, and too bad as well that Lord, who died last August at age 86, will not enjoy what’s sure to be a significant publishing event. The boy we meet in the opening chapters is not notable for his daring. James is a sullen kid at a “detestable” (but unnamed) prep school, who one day has the epiphany that he lusts after other boys, and that this will be his doom. He enters college, where doom presses in. But there’s a war going on. How logical: enlist and escape! So he does, and soon finds himself in a world of redneck boorishness much worse than school. Lord evokes all of this with an aggrieved drollery that makes the farfetched seem wholly believable. Consider the beautiful youth he espies on the first day of boot camp in Atlantic City: “He was wonderfully fair, features almost too fine, a Botticelli of angelic allure, tall and slender.” It’s time to choose a roommate, so Lord follows this vision into a two-bunk room, sticks out his hand, and introduces himself. The youth “squinted, shifted, scowled, steely about the gray eyes, ignoring the presumptuous hand, then at last, however, snarled, ‘Teves. Joe Teves.’” Aghast with the certainty that Joe Teves has seen the homo in him, Lord backs off. “My roommate, needless to say, never became my friend, much less a buddy, barely an acquaintance. Good looks went bad in a hurry. Botticelli, Caravaggio all mutated almost overnight into Hieronymus Bosch.” Boot camp is an ordeal: “Even Teves whined in his sleep.” The sensitive Lord at age nineteen realizes that he must harden himself lest his fellow recruits detect “the guilty presence of a pansy weakling in their midst. So I had to be careful. This called for a devious bent, which I cultivated.” Lord unapologetically charts his deviousness throughout the memoir. To be gay in the 1940s required subterfuge, for exposure meant prison or worse. But in Lord’s case, it went further than that. He was an æsthete, a lover of Thomas Mann, Beethoven, Cézanne, and Picasso, and he possessed a keen sense of empathy, which also required subterfuge. The unimaginable cruelties of worldwide war were obliterating the very meaning of art, of empathy. This is the fulcrum of Lord’s story: how does a connoisseur of the best that civilization offers survive the worst that it offers? It’s an old story, to be sure. However, Lord’s version is original, surprising, frequently scary, always vivid, and, every now and then, weirdly lovely. Lord gets his first inkling of the horrors to come at an airbase near Reno, Nevada. On a walk with an acquaintance he notices “a high blank-faced fence of dusty planking festooned on top with rusty barbed wire. As we came closer, you could hear yowling on the other side.” This shocks him. His friend “snickered, sneered, and said it was a little taste of hell. Base stockade. MPs beating on the prisoners for the fun of it.” Lord is incredulous. His companion says, “Of course. The army’s a joke on everyday decency! We’re in the murder business, kid. That’s dialectical idealism for you. Toe the line, and toe it tight, or one of your buddies’ll beat the shit out of you.” Lord resists that logic. “I was outraged. The United States doesn’t do things like that.” His older, more cynical friend sets him right. Lord runs off, beset with the idea that he should somehow do something about this abuse of power. He can’t, of course, which proves the germ of an ever-growing sense of complicity. Seemingly random events take Lord from the airbase to a military intelligence training program at Boston College. Erudite, frosty Jesuits hold forth on France; it’s late 1943 now, and the Army has foreseen the need to bone up on all things French. One of the great incidentals of this book concerns the creaking vastness of the government’s war effort and its pervasive symbiosis with civilian life. It’s hard to imagine that degree of mobilization today. (Boston College devoid of regular students, replaced by spies in training?) At any rate, Lord’s swerve of destiny is a boon for the Francophile in him. He also enjoys Boston’s startlingly lively gay scene, Lord’s depiction of which provides another nice incidental. Who knew that the old Statler Hotel, now the Park Plaza, harbored in its lobby a gay bar to which straights were mostly oblivious? Passers-by apparently looked at the throng of boisterous young men in uniform, a good number of them plastered against each other, and saw not queers but just another GI drinking party. It’s quite an education for a kid who left school in flight from his own queerness, but that education has only just begun. A traumatized France greets Lord when he arrives in July 1944. The last of the Germans are getting kicked out, the French are ecstatic but feeling murderous about the Nazi collaborators still among them, and the Allied armies—bloodied but, in victory, ferocious—are erecting enormous ad hoc bureaucracies to try to manage the mess. Young Lord doesn’t adapt well to his niche in the machine. One of his most endearing traits is his ability to infuriate assholes. A sympathetic major observes, “You seem to be inhabited by a unique faculty for antagonizing your superiors.” Lord’s problem is that his superiors countenance mistreatment of German prisoners and hordes of detainees of many nationalities. It’s a revelation to read Lord’s descriptions of the conditions in American-run concentration camps that held not only confirmed enemies, but also huge numbers of unfortunates known as “displaced persons” whose wartime complicities were thought suspect. Imagine present-day Guantanamo on an epic scale: scant evidence, harsh judgments, routine torture. Lord bucks the system and suffers the consequences, but nonetheless feels haunted by a sense of complicity and guilt. It’s an amazing testament to one individual’s struggle with a barbarism mostly erased from triumphalist accounts of Nazi Germany’s defeat. Here’s where the “queerness” of Lord’s war mostly resides. His gay point of view includes much that is sexy in the usual sense. But what really stands out, what one suspects will be most enduring about this remarkable memoir, is the way in which Lord’s outsider-ness gives him a particular perspective and a distinct moral compass.