4th Street Feeling

by Melissa Etheridge

Island Records

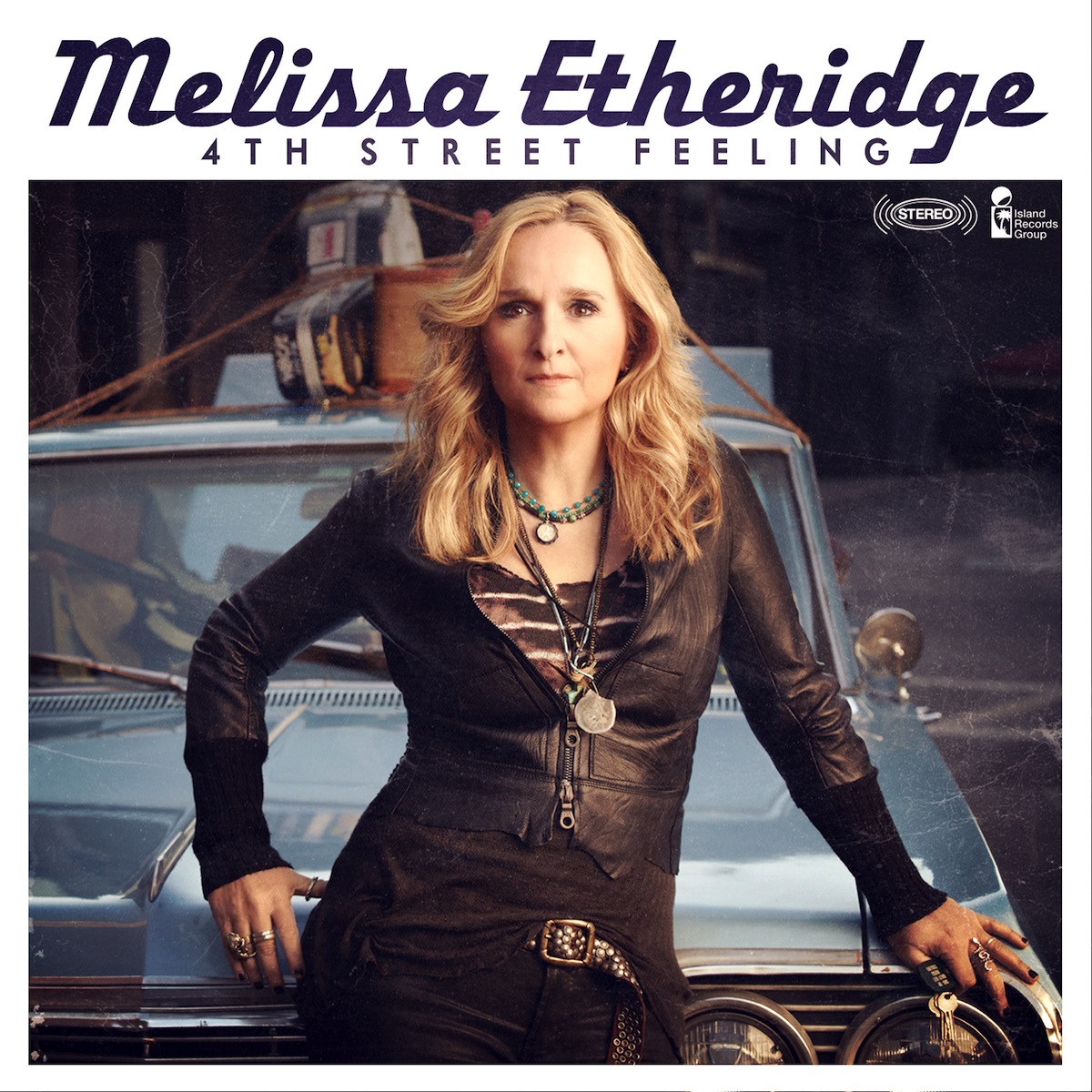

REBELS don’t walk. They drive. Kerouac went on the road by bus and truck; Dylan is still singing about a “hopped-up Mustang Ford.” Without that now iconic 1949 Mercury, James Dean might have become a rebel without a car. Working within this automotive American tradition, veteran rocker Melissa Etheridge has titled her latest album (her twelfth) 4th Street Feeling. On its cover, the Oscar winner and two-time Grammy winner stands confidently in front of a teal Chevy Impala. A suitcase and guitar are strapped to the roof while a leather-jacketed Etheridge holds the keys as if ready to roll. “Take me away, way back to that 4th Street feeling now,” she sings on the bluesy title track, “when everything I had I could fit inside my Chevrolet.”

The lyric is probably a nostalgic one, since, at age 21—thirty years ago—Etheridge packed up everything she owned and drove from her native Kansas to Los Angeles, where she played women’s bars and nightclubs before signing with Island Records in 1986. Every bit the starving artist back then, she once hocked a typewriter for forty bucks—the same one she used to write her lyrics—so she could take a girl she liked out for Mexican food.  Read the singer-songwriter’s 2001 autobiography, The Truth Is…: My Life in Love and Music, and gain a fuller sense of how personally charged her catalogue truly is: Etheridge’s oeuvre is nothing if not confessional. She even reproduces a diary entry from 1976 when, falling for a girl named Jo at a Christian youth summer camp, she scribbled: “I need her! I must be goin’ crazy!” The inspiration behind an early song like “You Can Sleep While I Drive” was a cross-country trip (alongside a girlfriend named Kathleen) in a Toyota, performing anywhere they’d let her. Meanwhile, on “Rock and Roll Me,” a slow burner that closes her newest album, she croons in her smoky alto: “I’ve never had a first time with a familiar touch./ It’s been a long, long, long, long, long time.”

Read the singer-songwriter’s 2001 autobiography, The Truth Is…: My Life in Love and Music, and gain a fuller sense of how personally charged her catalogue truly is: Etheridge’s oeuvre is nothing if not confessional. She even reproduces a diary entry from 1976 when, falling for a girl named Jo at a Christian youth summer camp, she scribbled: “I need her! I must be goin’ crazy!” The inspiration behind an early song like “You Can Sleep While I Drive” was a cross-country trip (alongside a girlfriend named Kathleen) in a Toyota, performing anywhere they’d let her. Meanwhile, on “Rock and Roll Me,” a slow burner that closes her newest album, she croons in her smoky alto: “I’ve never had a first time with a familiar touch./ It’s been a long, long, long, long, long time.”

It’s been a long time and a long road for the musician and activist whose 4th Street Feeling looks homeward in other ways as well. Her first stop is “Kansas City,” an electrifying opener in which Etheridge sings that she has “just a hundred miles to go on half a tank of gasoline/ Lucky Charms and Tic-Tacs and Mom’s amphetamines” in “my old man’s Delta 88.” From there a harmonica revs like an engine. Etheridge has no problem producing the kind of heartland rock delivered in the folksy spirit of Springsteen and Crow. She’s known for her howling, too, and on “Shout Now” you can practically hear her vocal cords rattle as she belts “It’s time for dignity/ It’s time for pride.”

But when hasn’t Etheridge made time for pride? She outed herself without any preplanning in 1992 at the inaugural ball for Bill Clinton. Swept up in the moment, she followed her friend k.d. lang’s lead and told the crowd the truth. “I walked up to the microphone and said, ‘Hi. I’m real proud to say I’m a lesbian.’ The crowd went crazy. K.d. gave me this huge hug. It really startled everyone, including me.” Her truth-telling was rewarded with her biggest commercial success to date. On the heels of a disappointing Never Enough, her “coming out” album Yes I Am went platinum six times over with gut-wrenchers like “I’m the Only One” and “Come to My Window.” Your Little Secret was an even bigger commercial success in 1995, but it was “Yes I Am” that remained on the album charts for nearly three years.

Around this time, the ever rebellious Etheridge began to remake standard notions of the family. She and girlfriend Julie Cypher accepted a sperm donation from none other than David Crosby, who, according to her memoir, dropped off the goods in between rehearsals with Stills and Nash in L.A. Comically enough, Etheridge recalls: “I remember that we had painters working on the house, and we wondered what they would think when David Crosby stopped by the house to deliver a curious-looking brown paper bag.”

Etheridge has remarked that music critics tend to ignore her, as she has never been a “critics’ performer” and “never a cerebral songwriter.” She might be surprised to learn, then, that her love songs are the source of scholarly interest in a work by professor of literature and women’s studies Carla Freccero. In her Queer/Early/Modern (2006), Freccero places love songs such as “I Want You” and “I Really Like You” in the lyric tradition of Petrarch and Labé. She writes that “conventionally gender-marked activities such as shaving, painting one’s eyes, wearing suits, wearing (cigar) rings, letting someone drive one’s car, and tattooing the name of one’s beloved on one’s body are unmoored from gender determination.” A more obvious feature of Etheridge’s interest in gay and lesbian issues is “Scarecrow,” her 1998 elegy for Matthew Shepard. The song is equal parts grief and outrage—“They beat you and they tied you/ They left you cold and breathing/ For love they crucified you”—and marked by the same outrage that upset her during her first world tour in 1988 and trip to the Holocaust museum at Dachau. Learning that the officials refused to recognize the gay and lesbian people who died there, Etheridge recounts in her memoir: “I sat down and wept. I couldn’t believe it. … It was the first time I had a recognition of myself as a lesbian in relation to the rest of society. … And here I was, standing in front of a place that had executed people just because they were gay. It was a powerful moment. A defining realization.”

The anthems of Yes I Am still verge on the overblown, which is why 4th Street Feeling strikes the right chord by hitting the brakes just a bit. With the help of producers Jacquire King (Kings of Leon, Norah Jones) and Steve Booker (Duffy), Etheridge plays all the guitars without overpowering the production. “It’s pretty when you’re young/ Just a pity when you’re old,” she sings, sounding a bit world-weary on “The Shadow of a Black Crow.” This is a promising road for Etheridge to take: since men continue to dominate the rock pantheon, it would be interesting to see Etheridge grow old and craggy in the vein of Bob Dylan and Neil Young, giving us the wisdom of later life from an entirely female perspective. “I Can Wait” could roll on for well beyond its three-and-a-half minutes; it features a strummy acoustic guitar and Etheridge vowing “I won’t change/ I won’t fade from the dark and strange. … I will stay right here.” Clearly, Etheridge’s wheels keep on turnin’.

Colin Carman, PhD, will serve as a Mayers Fellow at the Huntington Library; he manages a blog of film criticism at colincarman.com.