UNTIL RECENTLY, it seemed that camp was and would remain a phenomenon of the 20th century—camp, in all its manifestations: as a theory of æsthetics and style; as coded communication and performativity; as a site of humor and parody; as provocative social commentary. But if camp as a mode of artistic expression has fallen dormant, it remains a category favored by queer theorists to capture a certain modality of gay art and life of the past. The latest is David Halperin in a recently published book, How to be Gay (2012). The book contains an entire chapter devoted to unpacking the elusive meaning and significance of camp. But before looking at Halperin’s analysis of camp, a brief history of the word seems necessary.

In fact, the word “camp” has an extensive three-and-a-half-century history that began in 1671. Mark Booth traced the etymology of camp in an essay “Campe-Toi! On the Origins and Definitions of Camp” in the anthology Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject—A Reader (1999). He found the earliest known reference to camp in a play, Molière’s Les Fourberies de Scapin (1671), in which a character advises the following “campy” maneuver: “Stick your hat on at an angle and look disreputable. Camp about on one leg. [Campe-toi sur un pied.] Put your hand on your hip. Strut like a comedy-king!”

In the Oxford English Dictionary, two early references signify camp as performance: “One might say, ‘How very camp he is,’ referring to ‘actions and gestures of exaggerated emphasis” (Passing English of the Victorian Era: A Dictionary of Heterodox English, Slang and Phrase, 1909); and “Boys and men with painted faces and dyed hair flaunt themselves camping and whoopsing for hours each night” (New Broadway Brevities, 1931). Camp is often defined through checklists. For example, in Camp: The Lie that Tells the Truth (1984), Philip Core includes a catalogue of nearly 200 items to identify camp, including Joan of Arc and Empress Zita, the last empress of Austria, queen of Hungary, and queen of Bohemia; top hats, Lacoste T-shirts and underwear; nurses and Nazis; plastic and peacock feathers. Camp is an ever-shifting part of speech with distinct usages—as an adjective, campy; as a noun, the subject of this essay; as a verb, to camp (it up).

Before camp, there was dandyism. From the late 18th through the 19th century, dandies paid particular attention to personal appearance. It was cult of self inextricably connected to societal rebelliousness. (See Figure 1.) Oscar Wilde exemplified the dandy both as a writer and a public persona, remarking that “Dandyism is the assertion of the absolute modernity of Beauty” and that “One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.” Michael Patrick Gillespie wrote in Oscar Wilde and the Poetics of Ambiguity (1996): “Wilde’s evocation of the dandy’s milieu seems unmistakable, for it recurs in scene after scene of The Importance of Being Earnest…. [I]ndividuals in the play neither completely submit to the authority of public institutions nor irreversibly defy society’s jurisdiction.” The dandy and the camp both disrupt the flow of social convention. Both are in performative roles and both are stigmatized as outsiders or outlaws, persecuted, and, at times, legally prosecuted.

Hollywood film classics had the power to attract many gay men to glamorous female stars, whom they idolized. Movies embodied camp, from pathos-overloaded melodramas—Sunset Boulevard, All About Eve, and Grand Hotel—to historical costume dramas, such as Queen Christina and Cleopatra, in which Elizabeth Taylor winks campily at Caesar upon entering Rome in over-the-top spectacle. (See Figure 3.) Camp was present in all of Busby Berkeley’s musicals, notably 42nd Street and the “Gold Diggers” series (1933, 1935, and 1937). Even horror films had the capacity to display unhinged camp dementia, exploiting the iconic camp stature of Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, and Tallulah Bankhead in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte, and Die! Die! My Darling! (See Figure 4.) Camp extends from the movies of Mae West—who said, “Camp is the kinda comedy where they imitate me”—to John Waters’ entire œuvre. Commenting on Boom!, a 1968 film adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ play, Waters remarked that it’s “beyond bad, the other side of camp—a film so genuinely beautiful and awful that there is only one word to describe it: perfect.”

Camp Followers

For more than a century, there have been camp followers who scrutinized every manifestation of camp—high versus low; pseudo versus pure; pop camp and counter-camp; camp as distinct from kitsch. In his novel The World in the Evening (1954), Christopher Isherwood distinguished between high and low camp. The character Charles dismisses camping as it exists in “queer circles”: “You thought it meant a swishy little boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich?” Isherwood goes on to define high camp as “the whole emotional basis of the Ballet, for example, and of course of Baroque art. … You see, true High Camp always has an underlying seriousness. You can’t camp about something you don’t take seriously. You’re not making fun of it; you’re making fun out of it.” Then he alludes to a gay sensibility, concluding the passage with, “You have to meditate on it and feel it intuitively, like Lao-tse’s Tao.”

Tennessee Williams saw camp not as redemptive but as oppressive, writing in his 1975 Memoirs: “Of course, ‘swish’ and ‘camp’ are products of self-mockery, imposed upon homosexuals by our society. The obnoxious forms of it will rapidly disappear as Gay Lib begins to succeed in a serious crusade to assert, for its genuinely misunderstood and persecuted minority, a free position in society which will permit them to respect themselves, at least to the extent that, individually, they deserve respect—and I think that degree is likely to be much higher than commonly supposed.” In his Assorted Maxims and Epigrams, Charles Ludlam wrote that “Camp is motivated by rage.” In Wings of Friendship: Selected Letters, 1944-2003 (2005), Ned Rorem disagreed, writing this to critic John Simon: “You suggest that camp is violence in check, [but]it isn’t that like calling minor the sad side of major? … Personally I don’t believe camp intends to be hostile.” Camp can be used as a homophobic epithet, as in Ernest Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast (1964), where the line “Take your dirty camping mouth out of here” is his way of outing a character to the cognoscenti.

In 1964, Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” was published in the Partisan Review (later included in her 1966 collection of essays, Against Interpretation). The 58 notes were a definitive taxonomy that analyzed, defined, and demystified the inner workings of camp. (See Figure 5.) Although Sontag doesn’t explain the dedication or mention him again, she wrote: “These notes are for Oscar Wilde,” whose æstheticism she saw as embodying a camp sensibility. Wrote Wilde: “The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible.” And Sontag: “Camp is [understood]not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.” Elsewhere she writes: “Camp sees everything in quotation marks.” She associates camp with performance, “being-as-playing-a-role,” and with the artificial: “It is the difference … between the thing as meaning something, anything, and the thing as pure artifice.”

Sontag understood the centrality of gender and maintained that camp taste goes “against the grain of one’s sex.” She considered androgyny fundamental to the camp sensibility and offered examples from pre-Raphaelite painting and poetry: the sexless bodies in Art Nouveau prints and posters, presented in relief on lamps and ashtrays; the “haunting androgynous vacancy behind the perfect beauty of Greta Garbo.” (See Figure 6 at right.) She refers to camp’s propensity for excess, the love of the exaggerated, and the spirit of extravagance: “Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.” Or a headpiece made of bananas. In Busby Berkeley’s The Gang’s All Here, Carmen Miranda sported a colossal, banana-plumed headdress while singing “The Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat”: “Some people say I dress too gay, but ev’ry day I feel so gay, and when I’m gay, I dress that way. Is something wrong with that?” (See Figure 7.)

With the arrival of feminism and gay liberation in the 1970s, camp came to be seen as misogynistic, a parody of women. In Guilty Pleasures: Feminist Camp from Mae West to Madonna (1996), Pamela Robertson wrote: “Women have been excluded from discussions of pre-1960s camp because women, lesbian and straight, are perceived to have had even less access to the image and culture making processes of society than even gay men have had. … Women, by this logic, are objects of camp and subject to it but are not camp subjects.”

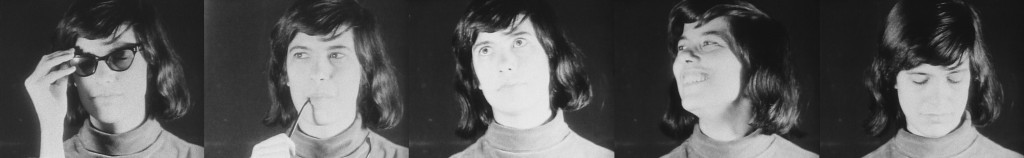

Figure 5. Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Susan Sontag, 1964

The death of camp seemed inevitable during the AIDS epidemic, when the use of any humor seemed inappropriate as a coping mechanism for massive loss of life. Andrew Holleran observed in Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath (2008): “Meanwhile the New York Post began to shriek lurid headlines that in more innocent times many of us had collected as High Camp: lovers jumping out of windows, hospital patients diving ten stories onto the sidewalk.” Edmund White eschewed camp as a stratagem in “Æsthetics and Loss” (1987): “Humor suggests that AIDS is just another calamity to befall Mother Camp, whereas AIDS in truth is not one more item in a sequence, but a rupture in meaning itself.” On the other hand, Paul Rudnick proposed in “Laughing at AIDS” (New York Times, 1993) that: “Gay writers, drawing on the repartee that is a form of gay soul, use camp, irony and epigram to, if not defeat the virus, at least scorn and contain it. AIDS is not the end of gay life or gay laughter. If people can’t giggle in hospitals or at memorials, all they can do is weep.” Decades before the epidemic, Robert Mazzocco wrote in The New York Review of Books (1966): “A person camps, a person becomes ‘beyond belief,’ when the everyday experience is no longer ‘to be believed.’ … For the camp temperament, the only possible solution to the intolerable problem of sincerity or of authenticity is to be deliberately insincere, to exploit, to ‘enjoy’ the unendurable.”

Eventually, by note 51 (of 58), Sontag illuminates what she designates as the “peculiar relation between Camp taste and homosexuality.” The camp æsthetic serves as the “propagandistic” means by which homosexuals will integrate into society. While homosexuals are the vanguard, “Camp taste is much more than homosexual taste.” Academic theorists refuted Sontag and “queered” camp with a new sense of urgency. Moe Meyers wrote in The Politics and Poetics of Camp (1993): “Camp is solely a queer (and/or sometimes gay and lesbian) discourse. … The un-queer do not have access to the discourse of Camp, only to derivatives constructed through the act of appropriation.” Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick viewed camp as a reparative, queer-identified practice, writing in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (2003): “To view camp as, among other things, the communal, historically dense exploration of a variety of reparative practices is to do better justice to many of the defining elements of classic camp performance.”

Camp versus Beauty

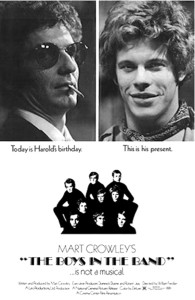

In How to be Gay, David Halperin advances a theory about two opposing yet symbiotic gay archetypes that are “indispensable to successful gay male social life”: the camp and the beautiful. He derived his thesis from Esther Newton’s Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America (1979), where she wrote: “At any given homosexual party, there will be two competing, yet often complementary people around whom interest and activity swirl: the ‘most beautiful,’ most sexually desirable man there, and the ‘campiest,’ most dramatic, most verbally entertaining queen.” While The Boys in the Band isn’t cited by Newton, it offers a precise schema of her theory of gay male relations. (See Figure 8.)

Halperin sees the division between the campy (Harold) and the beautiful (Cowboy) as an antagonistic, immutable division. A queen is effeminate and a turn-off, while trade is virile and desirable. He admits that “it’s sexist and politically retrograde.” But what’s a gay man to do? “It is unreasonable to expect gay male culture to dismantle the dominant social and symbolic system of which it is merely the lucid and faithful reflection.” But why not dismantle the dominant social order? As Edmund White wrote in reviewing Halperin’s book (New York Review of Books, Oct. 25, 2012): “I can sympathize with Halperin’s impatience with the current wave of gay assimilation, the bland effort to blend in with the ‘heteronormative’ crowd, but I would suggest we should look forward to a renewed progressive struggle for more adventurous lives.”

Undoubtedly some gay men have a preference for masculinity, but obsessions about body type should not preclude egalitarian relationships. Actually, such assumptions can be misleading, as Simon LeVay points out in Gay, Straight, and the Reason Why: The Science of Sexual Orientation (2010): “A great deal of diversity is present in the gender-related traits of gay men and of lesbians … Some gay men are so radically gender-nonconformist that they border on transsexuality,” while other gay men “[push]the envelope of masculinity beyond the heterosexual norm.” Even Sontag saw the subversive potential of camp when she wrote: “Camp is the triumph of the epicene style. The convertibility of ‘man’ and ‘woman.’ … What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine; what is most beautiful in feminine women is something masculine.”

That being the case, another genre of camp opens up when gay men are presented with an exaggerated masculinity. Our culture promulgates avatars of an over-the-top virility that lend themselves to caricature. Is there not something weirdly campy about Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Conan the Barbarian? (See Figure 9.) Alan Sinfield argued that there is a campy element to Tom of Finland’s drawings of hugely endowed musclemen, creations that are “sheer fantasy”: “Gay masculinity is not in any real way, ‘real’ masculinity, any more than camp is ‘real’ femininity. It is more self-conscious than the real thing, more theatrical, and often ironic. Manliness may be as camp as effeminacy.”

Ultimately, what defines camp? Sontag noted that “Camp taste is much more than homosexual taste. Obviously, its metaphor of life as theater is peculiarly suited as a justification and projection of a certain aspect of the situation of homosexuals.” As campy as Liberace may have been, he denied his sexual orientation throughout his life. In 1956, he won a lawsuit against the English tabloid The Daily Mirror for outing him without ever using the word homosexual, describing him thus: “the summit of sex—the pinnacle of masculine, feminine, and neuter. Everything that he, she, and it can ever want … a deadly winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromium-plated, scent-impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavoured, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love.” As definitions of camp go, that’s not bad.

Figure 1. Hugh Bonneville, Beau Brummell: This Charming Man, 2006

Figure 2. Alla Nazimova and Mitchell Lewis, Salomé, 1923

Figures 3 and 4. Elizabeth Taylor, Cleopatra, 1963. Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, 1962

Figure 5. Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Susan Sontag, 1964

Figure 6. Greta Garbo, Mata Hari, 1931

Figure 7. Carmen Miranda, The Gang’s All Here, 1943

Figure 8. Publicity poster for The Boys in the Band, 1970

Figure 9. Arnold Schwarzenegger, poster art for Conan the Destroyer, 1984

Steven F. Dansky has been an activist, writer, and photographer for more than fifty years. He is the publisher of Christopher Street Press.