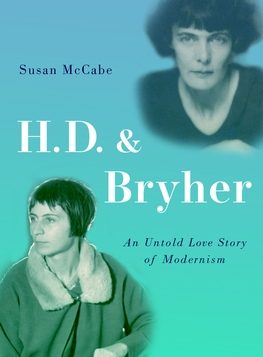

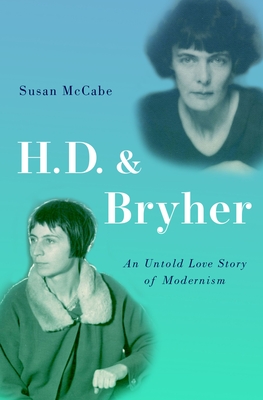

H.D. & BRYHER

H.D. & BRYHER

An Untold Love Story of Modernism

by Susan McCabe

Oxford University Press

424 pages, $39.95

BEST KNOWN for her poetry, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle, 1886 –1961) was also a novelist, memoirist, essayist, translator, and famously the lover of one of the richest women in England, Annie Winifred Ellerman (1894–1983), better known as Bryher. H.D. and Bryher were true lovers for over forty years. They met in 1918 during the emerging Modernist movement in art, literature, dance, and music. As part of the classicist revival movement, they shared an imaginative landscape that crossed boundaries populated by the art and myths of Greece, Egypt, Britain, and the Americas.

I was introduced to H.D. at the age of eighteen in a class on Greek mythology. Our professor read from her poem “Heliodora,” whose last lines captured my imagination: “A girl’s mouth/ Is a lily kissed.” Thinking of H.D. and Bryher, I’m reminded of Quentin Crisp, who, upon seeing the Marchesa Luisa Casati at the end of her life, saw Luisa as a reflection of himself, “a being of her own invention—not one of any particular sex or time or size or shape.” Susan McCabe’s compelling love story makes it clear that both women fall into this category of fabulous beings.

World War I profoundly shaped their worldview. During the war, H.D. experienced a series of traumas. Her brother Gilbert was killed in action, and her father Charles died soon thereafter. She was stricken with double pneumonia while nine months pregnant with her second child, Perdita (her first had been stillborn in 1915). Doctors had warned her that she and the baby might not survive, but miraculously she did. Moreover, H.D.’s already turbulent marriage to Richard Aldington, who had just returned from serving on the front lines in France and was suffering from PTSD, only added to her stress. She suffered a nervous breakdown as these events hammered her already fragile health and tenuous grip on reality.

Bryher was 23, identified as a boy, and took her name from one of the wild islands of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall. She aspired to be a writer and fell in love with Hilda after reading Sea Gardens (1916). Discovering that H.D. was recovering at Bosigran Castle at St. Ives, Bryher moved heaven and earth to meet the woman who had so inflamed her imagination. Having received Bryher’s calling card, H.D. invited her to “chat over tea.” Two more different-looking women would be hard to imagine. Bryher was only five-foot-two and had a bulldog jaw, while H.D. was six feet tall and slender as a birch.

Their meeting produced what McCabe calls “an electric charge, a set of recognitions” that were to last a lifetime. We follow the two women exploring the paranormal in search of manifestations of mind over matter. Like many interwar Modernists, they shared a passionate belief that the highest aim was to reach an equilibrium, balance, and growth. But in 1939, the search for their elusive ideal was rudely interrupted by Germany’s invasion of Poland, leading to World War II.

After living through five-and-a-half years of the Blitz in a small London flat, H.D. had a psychotic breakdown in 1946 that led to an extended stay in a sanitarium. Bryher confessed to a friend the humiliating truth that she had engaged a doctor and a nurse who had taken her place by H.D.’s side. She consulted with Hanns Sachs, one of the original psychoanalysts in Freud’s inner circle, who was a trusted friend of long standing. McCabe stresses the severity of the situation for H.D., who was hallucinating and thought that the war was still going on, and that Bryher and her daughter Perdita were enemy agents out to get her. Bryher was forced to stay out of sight for six months because of these delusions. However, after H.D. received shock treatment, the first thing she asked for was to see Bryher.

Where does myth end and reality begin? The ghost of Greek beauty and pagan mysticism spoke to these women. They sought miracles in the ruins and relics of past civilizations, freely navigating outside of present time and crossing between visible and invisible worlds. The striking paradox is that these very modern women sought inspiration from ancient cultures: Greek, Egyptian, Roman, Viking, and Biblical. They nurtured and cultivated each other’s gender fantasies. The question H.D. asked Freud was: “What do we do with our many selves that do not fit our bodies?” It is a question for the ages.

Susan McCabe’s book reads like something out of a Dan Savage column. H.D. and Bryher were polyamorous, bisexual, explored the physical and psychic connections between them, created improbable blended families, and were totally devoted to each other. We follow them through their explorations of the mythopoetic, ancient histories during two world wars, followed by nervous breakdowns, battles with family, and struggles with gender identity. This double biography is the untold story of two lifelong lovers who, together and apart, played a role in shaping Modernism and the sexual politics that lay ahead.

Cassandra Langer, a freelance writer based in New York City, is the author of Romaine Brooks: A Life (Wisconsin).