Diane Arbus: In the Beginning

by Jeff L. Rosenheim

The Met. 256 pages, $50.

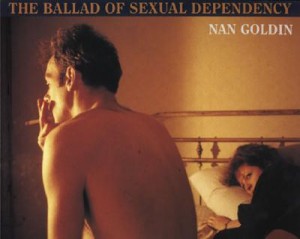

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Aperture. 148 pages, $35.

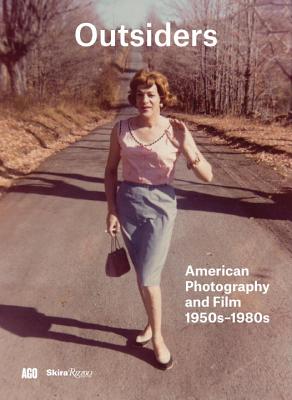

Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s–1980s

Edited by Sophie Hackett and Jim Shedden

Skira Rizzoli. 180 pages, $29.95

CULTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS swept across this country in the mid-20th century, affecting every aspect of American life, including the arts. A new wave of outsider artists underscored the mood of restlessness through powerful photography and filmmaking. Rather than romanticized versions of life, they provided authentic representations that often portrayed previously unseen subcultures, including those of variant sexual orientations and transgender identities. These works captured the existential malaise of an era. Whether brandishing a portable 16mm film camera or using a hand-held Rolleiflex on open city streets, outsider artists were anti-authoritarian and anti-institutional. They were subversive outcasts at the intersection of art and politics, race and class, gender and sexuality.

Last year, there were several major exhibitions from outsider artists in North America, including: Diane Arbus: In the Beginning, at the Met Breuer, a comprehensive survey from one of the most influential and provocative artists of the 20th century; Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency at the Museum of Modern Art, including 700 photographs in a disquieting and compelling slideshow; and an exhibition called Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s-1980s at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, which was a wide-ranging survey of outsider artists such as Arbus, Goldin, Robert Frank, Danny Lyon, Gordon Parks, Garry Winogrand, and the Casa Susanna collection.

While outsider artists have been central in representing American society—indeed were instrumental in transforming it—my focus here will be on those works that have challenged conventional sex and gender rules and expanded the discourse on sexual orientation and transgender identity.

The breathtaking Arbus exhibition includes more than a hundred never-before-seen photographs from long-sealed archives dating from her early career (1956 to 1962). It is a floor-to-ceiling, nonlinear arrangement of panels that is neither chronological nor thematic. Arbus’ work has always been controversial. When MoMA’s New Documents exhibition opened in 1967, introducing her to the general public, it included six photographs that represented the transgender experience. Those pictures provoked considerable outrage. Yuben Yee, MoMA’s photo librarian, arrived early every morning to wipe spit off these photographs, because her unabashed and unapologetic images aroused such transphobic reactions from spectators.

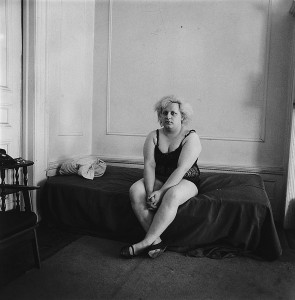

Arbus once wrote: “A photograph is the secret about a secret. The more it tells the less you know.” She made images throughout her career that depicted what had rarely been seen before: narratives of gender ambiguity and difference. Her subjects span the transgender spectrum, including cross-dressing female impersonation and performance drag with unambiguous titles like Female impersonator holding long gloves, Miss Stormé de Laverie, The lady who appears to be a gentlemen, and Transvestite at drag ball. She captures gender transitioning in A Naked Man Being a Woman, with a subject gesturing like Eddie Redmayne in The Danish Girl, concealing male genitalia between her legs. She appears as if backstage, half made up and without a wig, hand on hip and smiling through a parted curtain. In Seated man in a bra and stockings, she again displays gender discordance—eye makeup, garter, stockings, and pumps, but no wig—as the subject stares blankly, slouching in a chair. In her well-known photograph A young man in curlers at home on West 20th Street, her subject starkly confronts the viewer with unartful femaleness through crudely plucked eyebrows, eyeliner, mascara, lipstick, and manicured nails juxtaposed against incongruously rough hands, divulging masculinity and manual labor. In The transsexual operation, she photographed a 52-year-old woman after gender reassignment surgery. She examined intersexuality with Hermaphrodite and a dog in a carnival trailer, which is about biological dualism; a dog rests on the subject’s hairy leg, while the other leg is perfectly smooth.

It is significant that Arbus’ photographs were not taken surreptitiously, unlike so many street photographs. Instead, she cultivated friendships with transgender people and took their photos with their permission. She photographed Vicki Strasberg several times, such as in Transvestite at her birthday party, Seated transvestite with crossed ankles, and Transvestite with torn stocking. Arbus found outsiders to portray within the nocturnal realms of Times Square, whether inside 42nd Street movie theaters like the Apollo or the Empire’s second balcony, or underground in the hallucinatory dream-world of Hubert’s Dime Museum and Flea Circus.

Like Arbus, Nan Goldin exposes what was once invisible, bringing into public view an unseen world of sex and gender alternatives, while also exposing abuses of male power and domestic violence. Goldin captured the zeitgeist of the era in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, creating a vérité-style elegiac slideshow with music—a diary-like modern morality tale. Inside tenements, in windowless rooms with exposed brick walls, she constructed a system of carefully arranged metaphors (dirty bathwater, unmade beds). Her technique was to extend the snapshot æsthetic through the use of off lighting, poor focus, awkward poses, and harsh shadows to convey disruption, spontaneity, and immediacy.

Goldin objected to characterizations of her work as being about marginalized people. “We were never marginalized because we were the world. We didn’t care what straight people thought of us. … We were many people living in a similar lifestyle. There were some political beliefs behind it for some people, it was somewhat transgressive against normal society, but it was not about outcasts or marginalized people.” Still, most of her images suggest marginality to her viewers. For example, Greer and Robert on the Bed is an image that typifies her work. Greer Lankton, who had gender-reassignment surgery, was an artist known for her flamboyant, doll-like sculptures, which look like Garbo’s Camille on a deathbed with dark shadows beneath her eyes. It’s an image about survival with one skinny hand clutching the wrist of the other arm as if to support it. She is lost in contemplation, inaccessible to her lover Robert. The pair look away from each other. The bars of a brass bed suggest entrapment and confinement. These are two people at the edge of a failed relationship, and the masks on the wall insinuate a masquerade and duplicity. In The Ongoing Moment, Geoff Dyer wrote of Goldin’s photographs: “The bed was always there. It dominated the room, became the stage on which the ongoing Ballad of Sexual Dependency was enacted.” The unmade bed is the stage for enigmatic and prescient bedtime stories, for subjects on a mattress negotiating lovers, or alone, masturbating, or dying from AIDS.

The status of photography as a fine art emerged late in the 20th century, and what had little or no value earlier became part of lost-and-found expeditions into auction houses, flea markets, garage sales, and even rural farmhouses. The search was on for well-known, undiscovered, and anonymous photographs. Samuel Wagstaff, art curator and Robert Mapplethorpe’s life partner, went on binge-buying sprees for more than a decade, selling his photograph collection to the Getty Museum for more than five million dollars. In 2003, in a pile of papers unclaimed from a storage warehouse in the Bronx, rare Arbus prints were discovered. In 2007, John Maloof bought a derelict storage locker for $380 in which were contained some 100,000 negatives and nearly 3000 rolls of black-and-white and color film made by Vivian Maier, an unknown photographer who became a cause célèbre and the subject of the 2013 documentary Finding Vivian Maier. Her work, mostly street photographs, has been compared to that of Arbus because of its directness and candor.

At a New York flea market, Robert Swope unearthed 400 snapshots and three neatly preserved photo albums of great interest. He wrote in Casa Susanna, a book he co-edited with Michael Hurst: “I felt electrified. I had never seen anything like this that had not been clearly orchestrated as a party or a joke. … I seriously began tearing through the box, determined to find every single one of these photographs.” What he found were snapshots from Casa Susanna, a Catskill Mountain retreat for cross-dressers, a hideaway in Hunter, New York, in a rundown bungalow colony. Tito Valenti and his wife Marie operated Chevalier d’Eon from 1955 to ’63 and Casa Susanna from ’64 to ’69. (They also gave cross-dressing soirées in their New York City apartment.) Harvey Fierstein’s 2014 Broadway play Casa Valentina is about the Catskills retreat.

The Art Gallery of Ontario’s Outsiders exhibition included a collection of snapshots from Casa Susanna that were clearly taken by the participants themselves—an example of visually striking and intimate images that were made without artistic intention, showing their subjects engaged in everyday activities around the house. However, the snapshots are striking in what they reveal about an unseen outpost of American life.

The Ontario exhibition included films from the underground cinema movement such as Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963) and Shirley Clarke’s The Portrait of Jason (1967). Scorpio Rising is a 28-minute film that follows a group of young motorcyclists in Brooklyn garages and workshops as they prepare for an apocalyptic night on the town. Anger’s use of synchronization of sound and image anticipates Goldin’s work, which also uses montage and a color-sound relationship. The soundtrack contains eleven rock songs. Stated Anger: “I’ve never made a film using dialogue or speech.” In his underground film about biker culture, for example, the characters speak through a rock-and-roll soundtrack. Anger satirizes queer desire and sexual coding in Scorpio Rising, noting: “All my actors were straight. They were working class guys.” Nevertheless, he directed them toward a performative homoeroticism through pretend oral and anal sex play. They appear ritualistic, like those in fraternity initiations. However, rather than placing them behind closed doors, Anger encourages the viewer’s voyeuristic gaze.

The look of leather in Scorpio Rising provokes anxiety and pleasure within the visual materiality of masculinity along with additional regalia of biker subculture—belts, chains, dangling cigarettes, harness boots, Muir caps, orange-tinted aviator sunglasses, snaps, and zippers. (Think Marlon Brando’s character in 1953’s The Wild One.) The motorcycle itself is sexualized, and with piercing close-ups the bikers’ physiques are fetishized. The film satirizes narcissistic male grooming and its fantasies of power, mastery, and control—anticipatory preparation for a violent night out (similarly acted out by John Travolta some fifteen years later in 1977’s Saturday Night Fever).

Art critic Fred Ritchin, dean of the school at the International Center of Photography, wrote this about the representational and interactive potentials of hypertextual photography: “It is no longer just about looking but can be more ongoing, engaged, and potentially even helpful, with work submitted by outsiders and insiders alike.” Outsider artists can be powerful voices challenging assimilation, conformity, commoditization, and gentrification, depicting the vestiges of a disappearing GLBT culture and subculture; and preserving our memory, queer identities, experience, gestures, language, and objects. Outsider artists can develop representational strategies and visibilities that encourage complex and pluralistic understandings of identities. We are at the cusp of redefining gender, questioning the binaries of feminine and masculine, and pushing beyond the boundaries of biological determinism.

Steven F. Dansky, an activist, writer, and photographer for over fifty years, is the founder of Outspoken: Oral History from LGBTQ Pioneers.