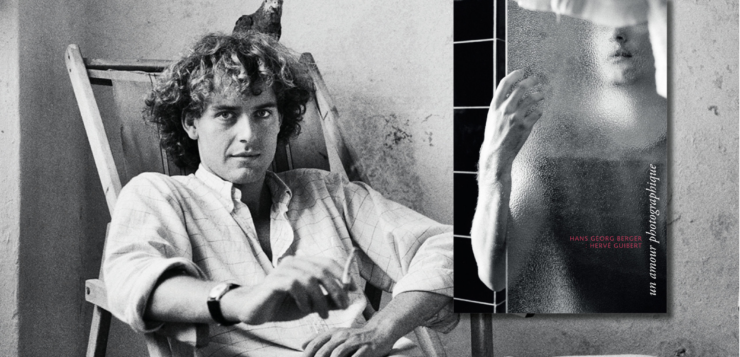

MY MANSERVANT AND ME

MY MANSERVANT AND ME

by Hervé Guibert

Translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman

Nightboat Books. 82 pages, $15.95

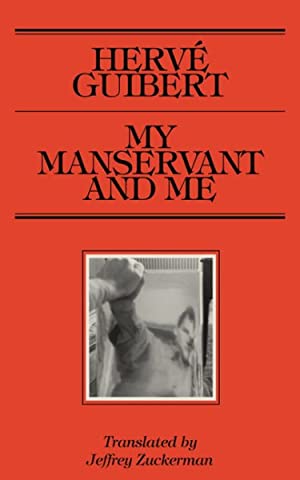

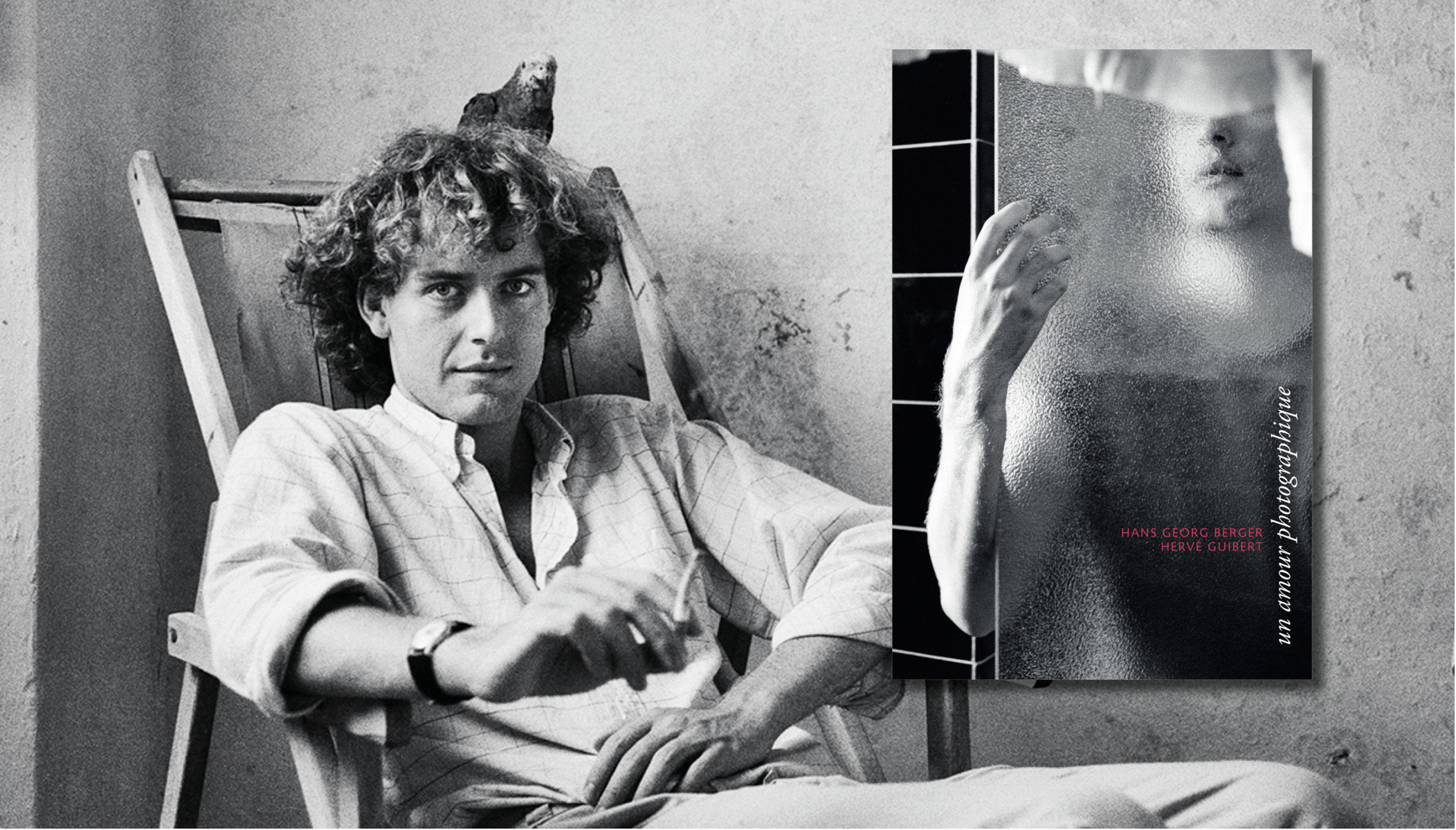

BEFORE his death from AIDS in 1991, the French writer Hervé Guibert wrote several novels and a hospital diary, all of which chronicled his life with the disease. Of his most important work in this category, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, the novelist Nina Bouraoui noted that Guibert had effectively told “how life with the virus became an existential adventure … when AIDS transformed our relationship with desire and sexuality forever.”

My Manservant and Me was the last novel that Guibert saw published. While not specifically referencing AIDS, it is the story of an aging homosexual whose bodily decline and dependence on a young, delinquent caretaker depict “an unrelenting and derisory hellscape of terminal illness,” in the words of Shiv Kotecha, who provides an excellent foreword to the English-language edition. Readers, beware: this little novel refuses to depict the aging process through rose-tinted glasses.

The manservant, whose name we eventually learn is Jim, has been in the narrator’s employ since he was sixteen. A former thief who spent time in a reformatory (the references to Jean Genet seem intentional), he’s devious and lazy, a young man who once had a leading role in a film and then never again appeared on the screen. The “master,” whom the manservant always addresses as “Sir,” has turned over all his affairs, including authorization to handle his finances, to Jim. In turn, the manservant has dismissed almost all the rest of Sir’s staff—the driver, the masseur, the nurse, the maid, the secretary, even the bellhop he would take along when he traveled. When he wipes Sir’s dangling genitals and wrinkly butt, the master feels that the manservant has reduced him to the status of an object: “a black console table that’s always a bit dusty.”

Guibert is clearly interested in the master-servant dynamic: What role does each perform? Who enslaves whom? What binds the two into a relationship? What, indeed, is the attraction, keen among some homosexuals, of a uniform? “I’ve always been fascinated, almost erotically so, by the outfits that minions of all sorts wear,” the master says. He has adopted an almost masochistic position vis-à-vis his manservant, who, in turn, indulges in ever more sadistic behavior toward his employer. “If you were in a nursing home, nobody would look after you like this,” Jim taunts him.

At another point, the manservant confronts Sir about his inheritance, revealing that he has been rummaging through the master’s papers and uncovered evidence of fraud: the master has despoiled his great-grandfather’s wishes to leave everything to the Humane Society. “Do I have it right that, as long as I’ve been with you, it’s presumably been thanks to the assistance of some fly-by-night lawyer that a huge scam has covered my room and board and paid for these pointless, cockamamie trips that haven’t done me the least good?” he chides. In turn, Sir has snooped on his manservant, opening a manila envelope in which a “voyeuristic faggot” of a film director has offered the young man a chance to be in a film “even more mediocre than the first.”

Back and forth goes the S/M dynamic. The manservant proposes that the master withdraw seventy million francs from his accounts so that he can buy “a very nice Picasso.” When Sir refuses to give Jim the money, the manservant reveals that he has already sold off several other very valuable paintings in the master’s possession. They fight, the old man falls backwards, the servant “dredges” him up. Later, trying to make his way from the couch to the bathroom, the master falls again. Though he cries out for help, the manservant leaves him helpless all night long. “You need to know how to be on the ground and not panic,” he tells Sir. When the master threatens to fire him, the manservant calmly replies, “I won’t be fired because Sir can’t do without me anymore … we’re stuck together to the bitter end.”

The subtle persecution continues. When the manservant gives Sir his routine injection of morphine, the master no longer feels the rush. Later he discovers the young man has been stealing the drug for himself and substituting tap water for his employer’s injections. “I wanted to slap him, but I couldn’t get my arm all the way up to his cheek.”

Soon the master is reduced to lying on the ground, curled up like a fetus. The manservant’s cruelties further mount up: he no longer holds up the master’s head to allow him to swallow properly; he kicks him and pisses on him. “If he had pissed on me when he was fifteen, at a push I might have liked it,” the old man says. “But now it’s too late, it’s just piss that smells like snail juice and goes cold immediately.”

Eventually, the manservant resumes giving the master his morphine injections. The visions the drug induces leave him no longer sure “whether my manservant is my son or my father.” The manservant says that when the master dies, he will go to work for his doctor, another morphine addict. In retaliation, the master pretends he does not recognize the manservant. “When he’s at his wits’ end, he’ll finally become interesting. He’ll lose his infuriating ordinariness.”

In comparison to To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, Guibert’s final book strikes me as slight—both in length and in importance. It seems a kind of reworking of Guibert’s earlier autofiction, Crazy for Vincent, about his obsession with a young, mostly straight skateboarder. Still, in the hands of Jeffrey Zuckerman, who has also translated Guibert’s collection of stories, Written in Invisible Ink, this is a compelling, even unforgettable, if truly repugnant, reading experience. My Manservant and Me is Guibert’s final expression of defiance against any comfortable notions we may have about the approaching end.

Philip Gambone is the author of five books, including the memoir As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II.