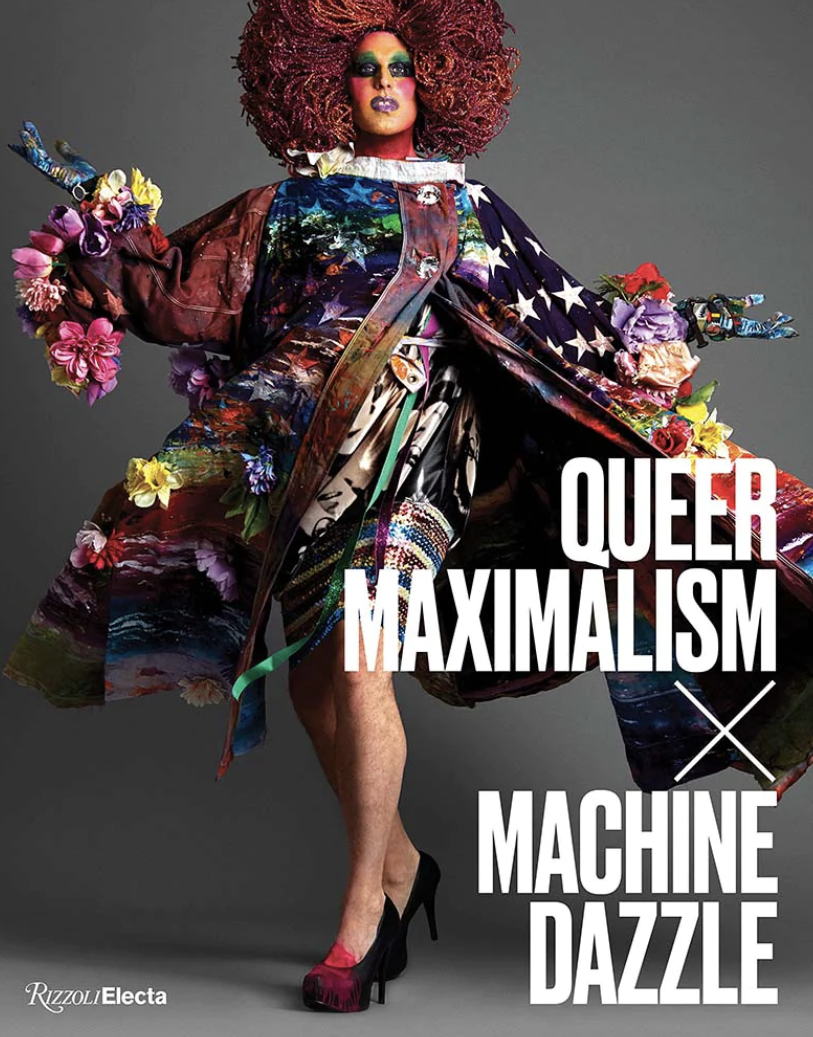

QUEER MAXIMALISM x MACHINE DAZZLE

Museum of Arts and Design, NYC

Sept. 10, 2022–Feb. 19, 2023

THE FIRST SOLO exhibition of Machine Dazzle, the nom d’artiste of Matthew Flower, which recently concluded at the Museum of Arts and Design in Manhattan, spread over two full gallery floors like synthetic blossoms. Comprised of over eighty creations built for performance, the costumes on display offered a queer spin on what theatrical design can be, blending found materials and foundational concepts with a spirit of radical reinvention. Familiar detritus like bottlecaps, plastic toy soldiers, and wine corks were refashioned, repurposed, and rearticulated. While an attention to theme and an intellectual foundation underpinned each specific design, there was a deliriously chaotic accretion to the pieces.

Self-taught as an artist, Machine Dazzle seemingly uses his sewing machine as other artists might use a paintbrush or chisel, sculpting and layering, conveying a sense of the improvisational instead of following a preconceived pattern. In a way, designs like those in Queer Maximalism function like the visual equivalent of Polari—the underground argot once spoken by buskers, beggars, circus artists, and homosexuals—an æsthetic slang borne out of the incubator of the downtown performance scene where Dazzle developed and honed his signature approach.

Starting in the mid-’90s, the collaborative commingling of his artistic DNA began with the glitter-crusted, Solid Gold-on-acid troupe the Dazzle Dancers (from which his name derives), supporting their ethos that “Having fun is a political act,” according to cofounder Mike Albo (aka Dazzle Dazzle). The cross-pollination of nightlife and performance spilled across clubs, lounges, the back rooms of bars like the Slide or the Cock, and performance spaces in collaborations with compelling “queerdos” and luminaries like Julie Atlas Muz, Big Art Group, puppeteer Basil Twist, and cabaret icon Justin Vivian Bond. That scene, stretching through the early years of this century, was in many ways a reaction to Mayor Giuliani’s crackdown on nightlife, as well as post-9/11 jingoism and security state posturing, resulting in a resurgence of seriously filthy fun.

Perhaps the fullest expression of Dazzle’s work comes in his partnership with MacArthur Genius grantee Taylor Mac, with the entire fifth floor of the museum devoted to the stage costumes he made for A 24-Decade History of Popular Music. This was Mac’s queer retelling of U.S. history through the American songbook, a lesson in the past reframed through the lens of marginalized people. For these performances, Dazzle designed what he termed companion costumes, allowing him to appear onstage as Mac’s dresser and to perform costume changes in front of the audience, a form of participation that transforms the traditional relationship between costumer and performer, backstage and onstage roles.

As with previous pieces, these designs incorporate kitsch and Americana, revealing the tension between whimsy and gravity that permeates Dazzle’s work while offering some of his most intricate constructions. Several images encourage the viewer to examine them more closely. There’s the macramé dress, a cross between a plant hanger and Japanese Shibari knots, from the Stonewall Riot/ Summer of Love section of Mac’s show. The Civil War section features a hoop dress: an imposing cage woven of imitation barbed wire and hot dogs. Why these items? As Dazzle told The New York Times, barbed wire was invented circa the 1860s. “And hot dogs! I read in a couple places that the American hot dog was invented in this time, by German immigrants.” For the decade that covers World War II, Dazzle’s design incorporates nods to both the atom bomb and the Slinky, both inventions of the time, mining the strains of kitsch and terror of that era. Prominently displayed in the exhibition is the outfit Mac wore for the decade of the 1960s, an allusion to Jackie Kennedy’s iconic pink Chanel suit and pillbox hat. Rendered in Ben-Day dots in the style of pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, with a shawl of Campbell’s soup cans on his shoulders, the pastiche evokes both the optimism and tragedy of the age.

Dazzle’s visual gestures aren’t exclusively queer, but they do transmit additional data to the receptive and the attuned. Just as Polari made a game out words, borrowing and twisting the grammars of the margins—Italian slang, Romani, cockney, Yiddish, and circus-speak in linguistic promiscuity—so, too, Dazzle’s designs send signal to fellow travelers, with nods to the illicit, outlandish and outlawed. These elements are recycled into something oddly beautiful: disposable plastic drugstore Halloween vampire teeth, a garland of Pez dispensers, a headpiece of 3-D glasses—a bricolage borrowed from drag and burlesque that draws a line to performers of previous eras, like the acid drag of the Cockettes and the giddy debauchery of Leigh Bowery.

As additional photos and the accompanying exhibition catalog from Rizzoli reveal, Dazzle’s theatrical ensembles aren’t bound by the footlights or the proscenium arch. They are equally at home at public spectacles in New York City, from parades (Coney Island Mermaid, Halloween, Easter) to queer liberation marches, and events like Night of 1000 Stevies.

Dazzle says his costumes are like living sculptures: they morph and evolve through use and wear. While it’s hard to capture the exact alchemy that marries performer and costume in a museum setting, video clips and elaborately articulated mannequins, swanning through the air or scaling walls, provide a sense of that unique fusion. Ultimately, the show’s expansiveness allows viewers to marvel at the paradoxes inherent in Dazzle’s signature style: playful yet rigorous, arch but accessible, intricate and unsubtle. It’s a more-is-more mode of do-it-yourself glamour pitched to the receptive viewer: effusive, dizzying, and, in the parlance, fantabulosa.

Taylor Mac’s 24-Decade History of Popular Music can be viewed at hbo.com/movies/taylor-macs-24-decade-history-of-popular-music.

Mike Dressel, a writer of fiction, essays, and criticism, lives in New York City.