When Pope Benedict XVi announced that he would be retiring from the papacy earlier this year, some people opined that he did so to escape the growing chorus of disapproval directed toward a scandal- plagued Vatican. His defenders said he was simply tired and wanted the position to be held by someone younger and more vital.

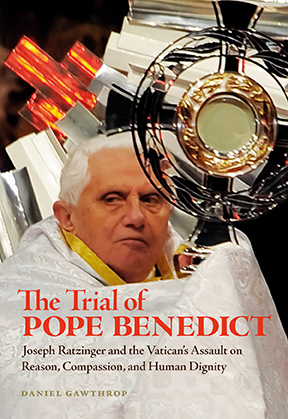

Vancouver-based author Daniel Gawthrop doesn’t make any secret about where he stands. in his new book, The Trial of Pope Benedict: Joseph Ratzinger and the Vatican’s Assault on Reason, Compassion, and Human Dignity

Vancouver-based author Daniel Gawthrop doesn’t make any secret about where he stands. in his new book, The Trial of Pope Benedict: Joseph Ratzinger and the Vatican’s Assault on Reason, Compassion, and Human Dignity (Arsenal Pulp Press), the writer recounts in exhaustive detail the litany of misdeeds perpetrated by the Vatican under this particular pope, the first to resign in centuries. it’s a damning indictment by the author, a gay man who describes himself as a “recovering Catholic.” Gawthrop’s previous books include The Rice Queen Diaries: A Memoir (Arsenal pulp, 2005) and Affirmation: The AIDS Odyssey of Dr. Peter (New Star Books, 1994). daniel Gawthrop spoke with me from Vancouver about the emotional and intellectual experience of researching and writing The Trial of Pope Benedict.

Matthew Hays: Are you Catholic yourself?

Daniel Gawthrop: I would not have written this book had I not grown up with an intimate knowledge of the faith. But I left the Church 26 years ago, just as I was finishing my un- dergrad studies, for the same reason most LGBT Catholics do: I could no longer reconcile who I was with an institution that thought I was “objectively and intrinsically disordered.” Still being in the closet was bad enough—and it would take another couple of years for me to come out. But remaining in the Church, as it was then being redefined by Pope John Paul II and Joseph Ratzinger, would have been a choice of such pro- found self-loathing as to be inconceivable. So today you could call me a “lapsed” Catholic, or even a Roman Catholic athe- ist, since I no longer believe in God. But don’t call me an “ex- Catholic,” because you never really leave the Church. you just recover from it.

As I say in the foreword, I like to think of myself as a Gra- ham Greene-style “cultural Catholic”: someone who, despite having left the faith, retains certain telltale behavioral traits consistent with Catholic identity. you know: a hair-trigger guilty conscience, an abhorrence of injustice, a fondness for formal ritual around family meals and community gatherings, and a fetish for symbolic pageantry and all things Italian, in- cluding The Godfather. Devout types think I’m using this book as some form of “therapy.” They mistakenly assume that I’m angry with the Church. But it’s not true. I got over the anger decades ago. A more accurate reading of my outlook these days would be akin to a somewhat befuddled anthro- pologist, shaking his head in wonder that anyone could still take seriously an ossified institution such as the Roman Catholic Church.

MH: What inspired this book?

DG: It was a former colleague of mine at the Canadian Union of Public Employees: Alexandre Boulerice, now the NDP Member of Parliament for the Montreal-area. During the spring of 2010, when CUPE Communications representatives from across the country were attending branch meetings in Ottawa, Alex and another Québecois colleague and I were having breakfast one day when the subject turned to the lat- est clerical sex abuse scandals in Europe. From there we began to share experiences of our respective upbringings, and the odd coincidence that so many of us union hacks were raised as Vatican II Catholics. Then Alex said something that really floored me: he had recently “resigned” from the Church by writing a letter to his bishop. His account of the “exit in- terview”—his bishop invited him out to lunch, to explain the letter—was brilliant. He told his bishop that leaving was an act of conscientious objection to all the evil the Church was perpetrating: the sex abuse, the treatment of women and gay people—everything.

When Alex told me this story, I wished I had written such a letter myself back in 1987, when I walked away from the Church. So I decided to do it anyway, retroactively. But to whom would I send this letter? Not my own bishop: Remi De Roo was one of the good guys, so a gesture like this would only have saddened him needlessly in old age. Then it hit me: Ratzinger, the man whose Inquisition had chased me away, had to be the one. Of course, the narrative voice for a letter approach was difficult to maintain over the course of an entire book. So, after completing a draft called “Dear Joe: A Dis- senter’s Encyclical,” I rewrote the whole thing as standard, third-person narrative.

MH: What would you say was the most horrific revelation you had while doing your research?

DG: The eighty-page victims’ statement to the International Criminal Court by the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP) makes for pretty grim reading. While most of its contents are not surprising, because the issue has been covered in the media for years, there is at least one case that qual- ifies as “horrific”: that of Marcial Maciel Degollado, the Mex- ican founder of the Legionaries of Christ, someone I describe in the book as “one of the biggest hypocrites and slimeballs in modern Roman Catholic history.” That Maciel was a bigamist who secretly fathered six children despite having taken vows of chastity was one thing. But he was also a pedophile sex ad- dict who raped two of his sons from the ages of eight to four- teen. Apparently, keeping several wives and mistresses didn’t do it for him. Maciel also insisted on being jacked off by young boys whenever he visited the seminaries of the Le- gionaries—all the while, of course, condemning consensual adult gay sex.

The really horrific part is not so much the bovine greed of the abuse—“the Caligulan gluttony of this treacly psy- chopath,” as I call it—but the fact that Pope John Paul II wanted to make this creep a saint. yes: Karol Wojtyla, who canonized more Catholics than all of his papal predecessors combined (and yet refused to beatify Archbishop Romero, who gave his life defending the poor of El Salvador), was propping up Maciel because the right-wing Mexican who shared his pope’s “dedication” to the Virgin Mary was such a good fundraiser for Christ. That is horrific.

MH: Any worries about lawsuits? Did you have this material vetted by lawyers?

DG: The research for this book involved material that was al- ready in the public realm. Of course, that fact does not absolve me of responsibility for my words. But I do think that my com- mentary on the characters involved, including the pope emer- itus, meets the usual standards for “fair comment.” So, no, I have no worries about lawsuits. Nor did Arsenal Pulp Press see The Trial as a title that needed to be “vetted.” Not unless there’s some risk of being sued for speaking truth to power. In which case, twitchy litigious types at the Vatican will need to remember that the “Church,” in the spiritual sense, doesn’t be- long to Rome. It belongs to the people—and to the legacy of all that great art, music, and literature it has inspired through- out the ages.

MH: How can the Vatican make amends for its past crimes and misdemeanors?

DG: I think “the Vatican,” which most people understand to mean the Curia—or the pope and the College of Cardinals— has no particular incentive to make amends. Change, if it ever happens in Rome, has always been glacial. It takes place over decades or half centuries—not months or years. It really re- quires something as explosive and all-encompassing as the sex abuse crisis, which has unfolded over a quarter century, to get this obscurantist coterie of geriatric celibates to recognize that something is seriously wrong with the Church, something that could ultimately threaten their power.

If Pope Francis is serious about sending a message to the world’s Catholics that his pontificate will not be business as usual, he could start by cleaning house. That is, by getting rid of corrupt clergy, from diocesan priests to Curial heavyweights, who have participated in child rape or its cover-up, or who have committed financial misdeeds for personal gain. That would be a big statement, because many Catholics have grown cynical about any prospect for atonement from the Curia. They also need to completely rewrite the canon law code on sex abuse that has governed the Church’s every decision on this issue since 1917. They’ve done enough groveling apologies. That’s not cut- ting it any more. They actually need to change how they do things. That also means recognizing married priests, women priests, and, yes, gay priests. Dream on, right?

MH: What would you most like people to walk away with after reading the book?

DG: What I would most like for people to take away from The Trial—whether they embrace the Catholic faith, another reli- gion, or no religion at all—is a sense that there was actually something worth fighting for with Vatican II; that, as annoy- ing as many of us find religion these days, the Catholic Church that emerged in the 1960s had the potential for truly progres- sive expression; that it was an open tent that encouraged dia- logue with other faiths and explored the world of ideas; that it was confident and generous, not the defensive and reactionary fortress it is today. For a short time, it was even a church that engaged in civic discourse in a manner that was meaningful and socially relevant.

The last gasp of this occurred, in this country, in 1983 with the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops’ critique of the business community and federal Liberal government. ethical reflections on an economic Crisis prompted a memorable piss- ing match between [arch-conservative publisher] Conrad Black and Bishop Remi De Roo that would be unthinkable today, be- cause Ratzinger dedicated so much of his time to dumbing down the Church by alienating its best minds. For readers who still embrace the faith and accept papal infallibility, or those who are troubled by what’s been going on but can’t quite articulate their frustration, I hope this book will open their eyes to the pathetic state of today’s Church and encourage them to walk away from it, as I and so many others have done.

MH: Did the timing of the Pope’s resignation throw you a bit?

DG: A bit? you can say that again. Actually, Benedict’s res- ignation proved to be a blessing in disguise. I had finished the book a year earlier, and parked it with a U.S. agent, but noth- ing was happening. So when the Pope made his announce- ment on February 11th that he was leaving at the end of the month—becoming the first Roman Catholic pontiff in nearly 600 years to resign—the subject of my book was suddenly part of the global news cycle, and I grew very anxious to get a deal. After parting ways with my agent, the obvious next move was to approach Arsenal Pulp Press, who had done such a great job on The rice Queen diaries. I’m still amazed at how quickly Brian [Lam] and his team put it all together. One of the funnier aspects of deciding when exactly to publish in- volved a serious discussion of when the narrative should ac- tually end. We decided to wait until the papal conclave was over, so I could say a few things about Benedict’s successor while capturing the last images of His Holiness leaving Vati- can City by helicopter for the Castel Gandolfo. That provided a kind of closure for the story. So, really, I have to thank Ratzy for helping us out. He did this book such a favor that I feel it is my duty to send him an autographed copy, as soon as the book comes back from the printer.

Matthew Hays, co-editor of the “Queer Film Classics” book series, teaches film studies and journalism at Concordia university, Montréal.