Published in: March-April 2012 issue.

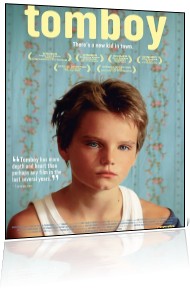

Tomboy

Tomboy

Written and directed by Céline Sciamma

Hold-Up Films

THE YOUNG FRENCH writer/director Céline Sciamma makes films that are empathetic and honest about the confusion that attends children’s sexual awakenings. Her first feature, 2007’s Water Lilies, dealt tenderly with the terrors and indignities of adolescent sexuality among a group of fifteen-year-old girls. Her latest film, Tomboy, explores an earlier and even more bewildering stage of life.