“IN 1620 Provincetown was a barren strip of land. What would a group of wayfarers, seasick and starving after a two month voyage to escape from what they considered to be a perverse England, have thought if they had known that the sandy cove they were setting foot on would someday feature drag bingo? … What would have happened if they had foreseen that their religious commune, known for its draconian anti-sodomy laws, would become part of a state (Massachusetts) that would be the first to legalize same-sex marriage? … Could these settlers have dreamed that the Charles Street Meeting House … would house the first national lgbtq newspaper?”

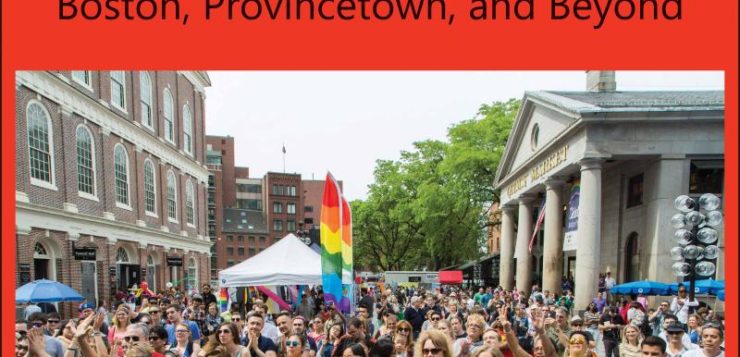

So begins The Hub of the Gay Universe: An LGBTQ History of Boston, Provincetown, and Beyond, by Russ Lopez, due out from Shawmut Peninsula Press in May 2019. From the Maypole of Merrymount in 1627 to the defeat of an anti-trans rights ballot question in 2018, the history, in Lopez’ words, “includes lavish nightlife and nightmare repression.” It has biographies of leading LGBT figures such as Ned Warren, who contributed his antique gay artifacts to the Museum of Fine Arts, and Blanche Lazzell and the other gays and lesbians who supported the Provincetown Theatre. It chronicles events like the secret Harvard tribunals of 1920 and the push for the anti-discrimination law that passed in 1989.

So begins The Hub of the Gay Universe: An LGBTQ History of Boston, Provincetown, and Beyond, by Russ Lopez, due out from Shawmut Peninsula Press in May 2019. From the Maypole of Merrymount in 1627 to the defeat of an anti-trans rights ballot question in 2018, the history, in Lopez’ words, “includes lavish nightlife and nightmare repression.” It has biographies of leading LGBT figures such as Ned Warren, who contributed his antique gay artifacts to the Museum of Fine Arts, and Blanche Lazzell and the other gays and lesbians who supported the Provincetown Theatre. It chronicles events like the secret Harvard tribunals of 1920 and the push for the anti-discrimination law that passed in 1989.

Lopez has studied, taught, and written about the urban environment, and has two previous books specifically about Boston, including Boston’s South End: The Clash of Ideas in a Historic Neighborhood. He has worked in Boston City Hall and the Massachusetts State House and has been active in politics and in LGBT issues. He is obviously the right person to have undertaken this history.

I conducted the interview with Russ, who is a friend, by e-mail.

Michael Schwartz: A central problem with writing LGBT history of earlier periods is documentation—finding and correctly interpreting the little evidence that has survived. What is the earliest LGBT evidence you found where we have details like names, dates, and places?

Russ Lopez: Shortly before Europeans began settling in Massachusetts, a horrible epidemic killed ninety percent of the Native population. It is unlikely we will ever know that much about their pre-contact society. The Pilgrims settled Plymouth in 1620. The first mention of same-sex activity is in 1629, and the first prosecutions were in 1636. The evidence presented in these first trials strongly suggest that there was a substantial underground of what we would call LGBT people by that time and most likely earlier.

MS: Another documentation problem is that most of what we have in earlier periods comes from white upper-class men and to a lesser extent women. We know about Harvard and Wellesley, but what evidence have you found relating to other LGBT communities in Boston?

RL: I was angered and saddened by the class, race, gender, and religion inequities in the evidence left by LGBT people, which don’t really begin to lessen until the 1960s. Arrest records are some of the best sources for the non-elite, as are tabloids. Yet we also see glimpses of their humanity: two African-American men living together in the 1790s, men arrested on the streets around Scollay Square in a police crackdown in 1918, and people challenging gender norms in every era. There is some evidence, but the lack of it is a sign of the depth of inequality.

MS: The material about Harvard men and Wellesley women is wonderful in its detail, with tons of name-dropping. For example, in 1906, Abram Piatt Andrew, Jr., a Harvard professor, met Henry Sleeper, who designed for Joan Crawford and Frederick March. They were intimates of Isabella Stewart Gardner, while Henry James was welcome to stay at Andrew’s Gloucester estate. Do you have a favorite well-connected couple from your research?

RL: The intellectual side of me wishes to have been a guest of Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett. The dinner conversation about literature and the gossip about writers must have been rich! But the carnal side of me would want to be a guest of Piatt Andrew and Henry Sleeper. What gay man could resist parties and peepholes with such handsome men?

MS: There are also details scattered throughout that are especially delightful for anyone who knows Boston. For example, Charlie Gibson, who established the Gibson House Museum in Back Bay in the 1930s, liked to hang around the Park Street subway station to pick up shoeshine boys. Do you have any favorite details like that?

RL: My favorite political tidbit is that the 1971 Pride March stopped in front of St. Paul’s on Tremont to protest how religions treated LGBT people. Then in 2007, the Religious Coalition for the Freedom to Marry met there before marching through the Common to support same-sex marriage. There are so many ironies in Boston history.

MS: You have a lot of details about Boston’s gay bars over the years. Any favorites?

RL: In the ’60s there was 12 Carver, owned by Phil Bayon, who liked to ride in a swing above the crowd. One man described it thus: “He’d get all juiced up and get in his swing. And she would sing ‘Summertime’ and she’d wear a big straw picture hat with ribbons and bows … and here she is, 300 pounds with this great big straw picture hat on.” Can you imagine staring up at a 300 pound drunk man on a swing?

MS: Of course, there are some non-delightful stories. The section on the secret Harvard tribunals of 1920 is heartbreaking.

RL: It is so hard to write about the tragedies of this history: the murders of trans women, the despair that led so many to drink or suicide, the AIDS years. I kept thinking of the bone-chilling fright those poor young men must have gone through, their terror as their futures collapsed when they were accused of being gay and then expelled. They were alone and no one would help them.

MS: I assume you used the historian’s customary source material—newspapers, memoirs, historical archives. Did you stumble across any surprising source material?

RL: There were amazing diaries and personal letters, but the most interesting was an unpublished novel by Frank O’Hara. It was mentioned by Brad Gooch in his biography of O’Hara, and I found a copy at the UC–San Diego Library. It’s not ready for print, it lacks an ending, but his description of life in Boston in 1948 is fascinating. Plus he couldn’t decide if one character should be a he or a she. He kept crossing out and changing their pronouns.

MS: You’ve dedicated the book to Ann Maguire. Why?

RL: Not only has Ann been a friend and mentor (she was my boss at City Hall), but also she has done so much for so many people. I kept running across her name while I was doing my research. This is a modest thank you for her kindness to generations of LGBT people over the past decades.

MS: In your section on domestic partnership benefits in Boston, you mention Andrew Sherman, your husband.

RL: I was personally involved in much of the recent history covered in the book. I was working for the Mayor while Andrew, my partner, was volunteering his expertise to implement the benefits. I didn’t go to the hearing, as we didn’t want to suggest there was any potential conflict of interest. But several other aides came running back upstairs to tell me how Councilor “Dapper” O’Neill was grilling Andrew as to who Mr. Pro Bono was. We almost passed out from laughing so hard. Mayor Flynn teased me for a month.

Michael Schwartz is an associate editor of this magazine.