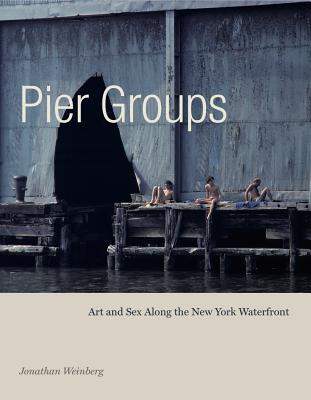

Pier Groups: Art and Sex Along the New York Waterfront

Pier Groups: Art and Sex Along the New York Waterfront

by Jonathan Weinberg

Penn State. 232 pages. $34.95

A FEW YEARS AGO, I came across an article about the black and openly bisexual photographer Alvin Baltrop, who photographed men and scenes around the New York City waterfront in the 1970s, specifically the now-demolished piers along the Hudson River in Lower Manhattan. The article included a few sample photographs, almost noir-like images of (sometimes naked) men cruising the ruined, abandoned piers. They were haunting glimpses of a long-vanished world, by a man who may have slipped into further obscurity. Baltrop had died in 2004, but a collection of his photographs,

, was at long last published in 2015, assembled by James Reid and Tom Watt. Discovering Baltrop, and then soon thereafter becoming fascinated with the life and work of David Wojnarowicz, led me to seek out even more information about the art scene along the piers in 1970s and ’80s. But there wasn’t much—until now.

Jonathan Weinberg describes Pier Groups as “part journal, part scrapbook, part traditional art-historical narrative.” The book is all of those things, but it’s also an incredible contribution to gay history in particular and to American art history in general. Weinberg’s scholarship over the years has been invaluable in documenting the art that sprang up in and around the piers. Without his efforts, artists such as Tava, Leonard Fink, Arthur Tress, Viti Acconci, Shelley Seccombe, and many others may have languished forever in the realm of the forgotten.

I moved to New York in 2003, long after the piers had been torn down by the city. I was a child and adolescent as AIDS ravaged a whole generation of gay men. When I came of age, and as I grew older, I always found myself wanting to know more and more about the men who came before me, about the gay world before Manhattan became sanitized, a playground mostly for the rich. Perhaps I romanticized the grubbier times, but in discovering Baltrop and Wojnarowicz, I wondered how many other artists had been hidden in the shadows, which artists were in danger of slipping away, unknown to the world because they were gay and because they worked in marginalized mediums and realms. Thanks to Weinberg and other art historians, the works of such artists are being preserved, catalogued, and presented to the world.

Weinberg has a personal stake in the matter. In his late teens, he frequented the bars lining Christopher Street leading to the piers. The piers were cavernous structures, long since abandoned, no longer connected to their once thriving commercial function. Weinberg called himself a “denizen of the waterfront and a member of the queer subculture.” He, like many of the artists he writes about in these pages, was drawn to the piers as a space “of freedom seemingly outside social control.” He writes that “the lure of the waterfront lay in both the beauty of its ruins and the opportunities its derelict state afforded for same-sex encounters.”

It’s true that the piers were a space where furtive sexual encounters occurred, but it was also a place where gay people were vulnerable to muggers, not to mention the rickety structures, where one false step could lead to a deadly fall. Eroticism mixed with danger became yet another aspect of its appeal for some gay men.

In this milieu arose a number of artists, some who became famous, such as Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar, but others who remained obscure, like Baltrop and Tava, whose two-story-high erotic paintings of nude men could be seen from any boat that circled Manhattan. The work of Wojnarowicz has been documented quite well, especially in Cynthia Carr’s fantastic biography, Fire in the Belly (2014). Wojnarowicz can’t be ignored when the art history of the piers is written, and Weinberg pays ample attention to him in these pages. However, the main strength of Pier Groups lies in its presentation of more obscure artists who finally get their due.

Heavily illustrated, Pier Groups introduces readers to the extraordinary photographs by Alvin Baltrop, Leonard Fink, Frank Hallam, Arthur Tress, Shelley Seccombe, Stanley Stellar, and others. Baltrop first started photographing the piers, he admits, for voyeuristic reasons, but “soon grew determined to preserve the frightening, mad, unbelievable things that were going on at that time.” Weinberg stresses the importance of dating the photographs, because one of the misconceptions is that many of the photos document transgressive and risky sex at the height of the AIDS era. As he writes, “If we are to bring the history of AIDS into the interpretation of photographs of sex in the 1970s at all, it should be to remember a time before the epidemic, when public sex between men was considered a liberating act.”

The photographs by these artists also “create a visual diary of the waterfront’s transformation over several years.” Seccombe, though not queer herself, beautifully documented the contrast between the ruinous aspect of the piers and the manner in which people used these spaces for enjoyable activities. Frank Hallam’s photographs are explicit and direct portraits of cruisers and cruising. Hallam, Seccombe, and Baltrop all “shared a sense that what they were seeing on the piers would not last and needed to be recorded.” Unlike those photographers, Leonard Fink took many pictures of himself at the piers. By day, Fink was a lawyer for the New York City Transit authority, and it seems no one in his family knew he was gay until his death from AIDS in 1993. His photos are carnal and frank—Fink standing in a doorway, wearing only a jockstrap; Fink getting fucked in the corner of a room filled with rubble. “The contrast of beauty and decay, joy and despair,” Weinberg writes, “is perhaps the most powerful and enduring trope of the pier photographs.”

During the 1980s, the piers buildings below 14th Street along the Hudson were demolished, one by one. With this destruction, a fertile ground for creativity vanished, not to mention wall paintings by the likes of Wojnarowicz and Tava, preserved now only in photographs. Pier Groups itself is a marvelous work of preservation, revealing this world and the artists who found those spaces so crucial to their artistic expression. It is a valuable work of scholarship, but also a fascinating glimpse at a place and time that may be gone but which, thanks to Weinberg, will not be forgotten.

Martin Wilson is the author of two novels, What They Always Tell Us and We Now Return to Regular Life. He lives in New York City.