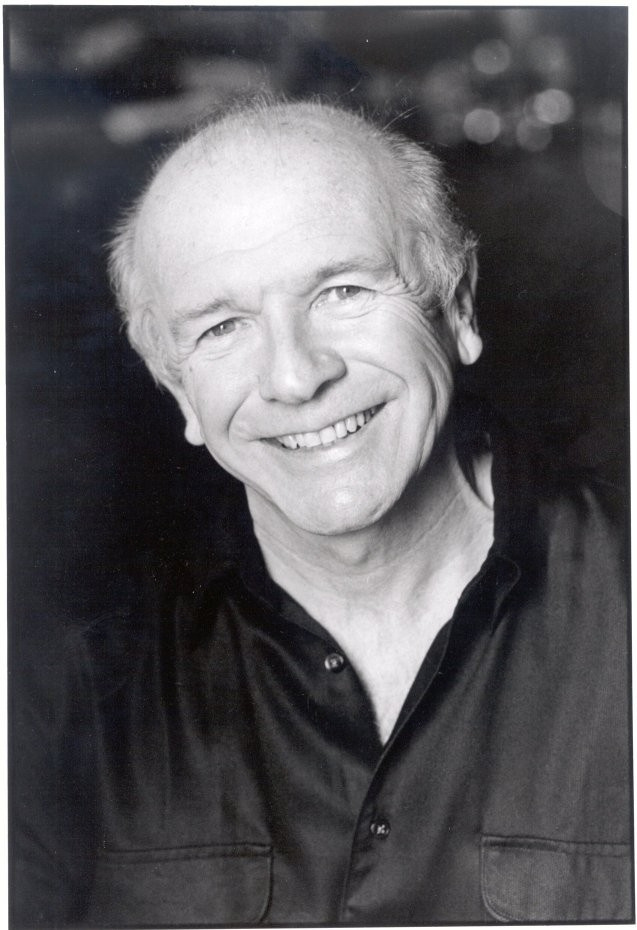

FOUR-TIME Tony-Award-winning playwright Terrence McNally (1938–2020) died on March 24th at his winter home in Sarasota, Florida, an early casualty of Covid-19. His death followed a stream of recent honors, including: the 2018 premiere of Every Act of Life, a documentary celebrating his career, at the Tribeca Film Festival; his election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in May 2018; and his receiving a coveted Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Theater Wing at the Tony Awards ceremony last June.

On November 3, 2018, Mayor Bill DiBlasio had honored the playwright on his eightieth birthday by declaring it “Terrence McNally Day” in New York City. Acknowledging his work as “a civil rights activist, championing marriage equality and tackling issues that impact the lgbtq community and people with hiv/aids,” the official proclamation reads in part: “Through his thought-provoking and witty plays, musicals, and operas, Terrence has engaged and uplifted generations of diverse audiences in New York and far beyond.”

My favorite passage from the plays of Terrence McNally is a speech that Josie makes in Unusual Acts of Devotion: “We can make each other so happy so easily and we seldom do. Put on a CD. Close the window. Open the window. … We make the easy difficult, the possible not. Yes, we somehow get through the day but with so many disappointments, so much hurt. We accept so little, all the while wanting so much.”

If there is a single major theme that runs through McNally’s plays, it is the simplicity of what we can do to make one another’s lives more satisfying. Small acts of grace dominate his plays: Johnny sucking the blood from Frankie’s cut finger in Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune; a stranger appearing at the funeral of Margaret’s young son and filling the church with a vibrant sound as she hums “Amazing Grace” to herself in A Perfect Ganesh; Buzz running a hot bath for his partner James after the latter soils himself in an attack of AIDS-related amoebic dysentery in Love! Valour! Compassion!; an elderly man, grieving the death of his wife, comforting the hustler he has engaged in Crucifixion; or Cal’s refusal to let go of the judgmental mother of his late partner, André, until she drops her emotional reserve and returns his embrace in Mothers and Sons.

But with sad-eyed realism McNally also dramatized the ways in which, by failing to rise to the occasion, we only intensify one another’s grief. Ruby and her brood sacrifice sweet-natured Clarence on the altar of their own insecurity in And Things That Go Bump in the Night. The four heterosexual interlopers in a Fire Island gay community consider whether they could love a child who was gay in Lips Together, Teeth Apart. A house party of gay men debate the use of the hate speech directed against them, and that they use against others, in Love! Valour! Compassion! And Claire Zachanassian is rendered inhuman by her inability to forgive the horrible wrong done to her years earlier in McNally’s book for The Visit.

As moving as McNally’s depictions of gay relationships are in plays like Love! Valour! Compassion!, Corpus Christi, and Some Men, the most haunting moments are those in which a character looks with intense longing at someone who is oblivious to their existence, as when Florimo is ignored by his lover, Vincent, who is rapt in his own music in Golden Age; or when Stephen stares at the torn Polaroids of his lovemaking with Mike years earlier and realizes that he and Mike have long since ceased to feel passion for one another in The Lisbon Traviata; or when Diaghilev buries his face in the discarded dance tights of his lover Nijinsky in Immortal Longings (earlier titled Fire and Air).

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, as gay men retreated into the safety of phone sex or watching porn at home on a VCR, McNally dared to remind us that salvation will never be found by isolating ourselves from one another, but in caring for one another with love, valor, and compassion. “We gotta connect. We just have to. Or we die,” one of his characters agonized. Retreating into a seemingly safe isolation was as deadly emotionally as contracting HIV was physically.

There is, then, a haunting irony to the fact that, having lost two partners and countless friends in the AIDS pandemic, McNally should die in the course of another pandemic, one that is giving us terms like “personal protective equipment,” “social distancing,” and “alone together.” At the time of his death, McNally was working on a new play titled Prunes that was set in a nursing home for elderly gay men and lesbians. No doubt such an institution as conceived by McNally would prove as outrageously eccentric yet as warmly supportive of vulnerable human dignity as The Ritz bathhouse in which McNally set his most flamboyant farce.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is the author ofThe Theater of Terrence McNally: Something About Grace (Fairleigh Dickinson, 2019).

Discussion1 Comment

As one of his characters said. “We gotta connect. We just have to. Or we die” makes me think of our current racial (histories racial) and police issues. Me, as a white man has never understood hate, disrespect, degrading of other humans for who they are since I was a young man. My values for human dignity as a teenager had made me wonder if I am from another planet because I felt none of this?

Aware of such racism and animosity was reinforced upon me as a young and adult gay man as well. These current times have got to make us stop and rethink how WE ALL WANT TO BE ACCEPTED AND LOVED AS HUMANS. We gotta connect with everyone’s nationality to understand that all of us are no different for wanting-needing the basics of life. I believe that when our government changes hands, the U.S. will heal from the current vial leader igniting the flames to divide and hate everyone just because. We just have to, Or we die!