We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power,

We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power,

and Pride in the History of Queer Liberation

by Matthew Riemer & Leighton Brown

Ten Speed Press. 368 pages, $40.

“QUEER HISTORY is about the fight to be … seen,” assert authors Matthew Riemer and Leighton Brown in their insightful and highly readable account of hard-won struggles for visibility by LGBT people from 1867 to 1994. Replete with vivid historical details and photographs, We Are Everywhere gives those struggles new heft and scope. The effort of transgender people to be acknowledged within the queer movement as a whole is made particularly clear.

Riemer and Brown, a gay couple living in Washington, D.C., are both trained as lawyers, and their legal acumen is reflected in lucid narration and presentation of evidence for more than one side of still unsettled arguments. This history has been assembled from records of formal and ad hoc organizations, personal recollections, and memorabilia held in gay, lesbian, and transgender archives.

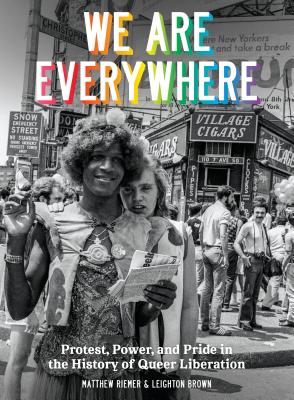

Striking black-and-white and color photographs supplement the text to offer what the authors intend as “a powerful record of the social space” occupied by queer people in the U.S. during the 20th century, especially the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. Some images are from more than 100,000 submitted to the Instagram account set up by the authors as a way to learn more about gay history, and many suggest broader context, such as the 1940s snapshot of a smiling young Japanese man, the boyfriend of another man, sitting on a hillside at a site identified as the “Tule Lake concentration camp,” where Japanese-Americans were incarcerated during World War II. Dramatic photos of protesters and rioters proclaim defiance and celebration, but so do pictures of house party revelers, or couples at a bar. Photographers are credited, and dates, places, and subjects listed when known, but readers are respectfully advised to avoid making assumptions about the sexuality, gender, or self-identification of anyone shown.

The narrative is inclusive, meeting the authors’ goal of contributing to the “expansive history of … the Queer Liberation Movement.” Following gender historian Susan Stryker, Riemer and Brown use “queer” to denote “different kinds of people who come together in the same place or for a common cause,” because—quoting Stryker—they don’t want to say “‘gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, drag, and butch individuals, along with [others]who might well be heterosexual.’” More specific terms are used as needed for historical accuracy or clarity.

We Are Everywhere is structured in four parts. An unusual but effective strategy is to open each part with a significant event from the end of its time period and then consider what led up to it.

Part I (1867–1968) opens in Chicago with the 1968 meeting of the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (nacho), as participants vote to adopt the slogan “Gay is good” proposed by astronomer and indefatigable gay rights activist Frank Kameny. Riemer and Brown describe what went on for decades before the conference to spur such a vote. “Prior to 1950 … people didn’t speak of coming out from a restrictive, isolated closet,” they explain. “Instead, they came out into an expansive gay world.” By the 1960s, gay men and lesbians were taking cues from Black Power, feminism, and anti-war crusades, and they were starting to protest publicly. However, activists differed on goals and tactics. Riemer and Brown note the words of black lesbian activist Audre Lorde: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives.” One strong divide was between activists seeking primarily to gain rights within the dominant hetero-normative culture, and those looking to change that culture’s norms.

As Part II (1968-1973) opens, trailblazing lesbian activist Barbara Gittings heralds a “Gay Liberation” era at the first Christopher Street Liberation Day rally in New York’s Washington Square, held in 1973. Many “attempts to grapple with oppression” in the five preceding years had borne fruit. In a watershed moment, activists used “militant otherness” to confront police raids on Stonewall in 1969, sparking days of riots. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) recruited large numbers of young gays and lesbians, and the Gay Activist Alliance was getting attention with “zaps,” which were agitprop disruptions of key meetings. With transgender people still marginalized, activist Sylvia Rivera and self-identified drag queen Marsha P. Johnson (she is shown on the cover of We Are Everywhere) broke from the GLF to found the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (S.T.A.R.) and opened a house for transgender street youth.

An astonishing number of people—perhaps 200,000—took part in the October 1979 March on Washington, which opens Part III (1973-1979). Marchers’ literature referred to “transpersons,” prompting Riemer and Brown to call this the first national march for queer rights. Conservative power was resurgent: Supervisor Harvey Milk had recently been murdered in San Francisco; Miami’s gay rights ordinance was repealed following the so-called “Save Our Children” campaign by pop singer Anita Bryant; and the New York Assembly failed to pass a gay rights bill on its eighth attempt. Although gay and lesbian activists persuaded the American Psychological Association (APA) to remove homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the category “sexual orientation disturbed” was retained and applied to transgender people. “In the mid-1970s,” the authors say, “while some Gay Rights got attention, only the ‘right gays’ got the benefits.” The space for “visible queers” got smaller, and when a Greenwich Village plaque honoring Stonewall was torn down in 1979, gay residents largely blamed “street gays and drag queens” angry about the plaque’s limited wording.

Part IV (1980-1994) opens with the memorial held in Los Angeles in 1994 to honor Dorr Legg, cofounder of the interracial homophile social club Knights of the Clock and co-publisher of ONE, Inc., the first homophile magazine in the U.S. Attendees included pioneer gay rights activists Jim Kepner and Morris Kight as well as legendary gay rights activists and rivals Hal Call and Harry Hay, who made peace for the day. Other “signs of a shared history” were emerging, say Riemer and Brown. Both official and alternative marches were held in New York to mark Stonewall 25, and while they started at different places, the marchers surprised onlookers by “merg[ing]into one queer mass” once they reached midtown. The need to contain and defeat the scourge of AIDS prompted extraordinary combined effort. The actions of “[a]group of gay and bisexual men in a Denver hospitality suite, inspired by lesbian feminists, changed millennia of medical practice” and made people with AIDS the experts on their own health, write the authors. The Supreme Court’s 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick decision upheld state anti-sodomy laws and ignited widespread outrage, while ACT UP debuted at Pride 1987 with a “concentration camp float” protesting Reagan Administration policies.

We Are Everywhere tells an intense story, and the endnotes point to areas for further investigation, such as the origin of popular myths about Stonewall, or why earlier riots went unnoticed. Riemer and Brown have written not a tidy history but what they call a queer one, with rough edges, unresolved conflicts, and multiple views. Riemer acknowledges inspiration from two history teachers, “who found joy in the details that others ignored.” This book conveys that spirit.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer living in Cambridge, Massachusetts.