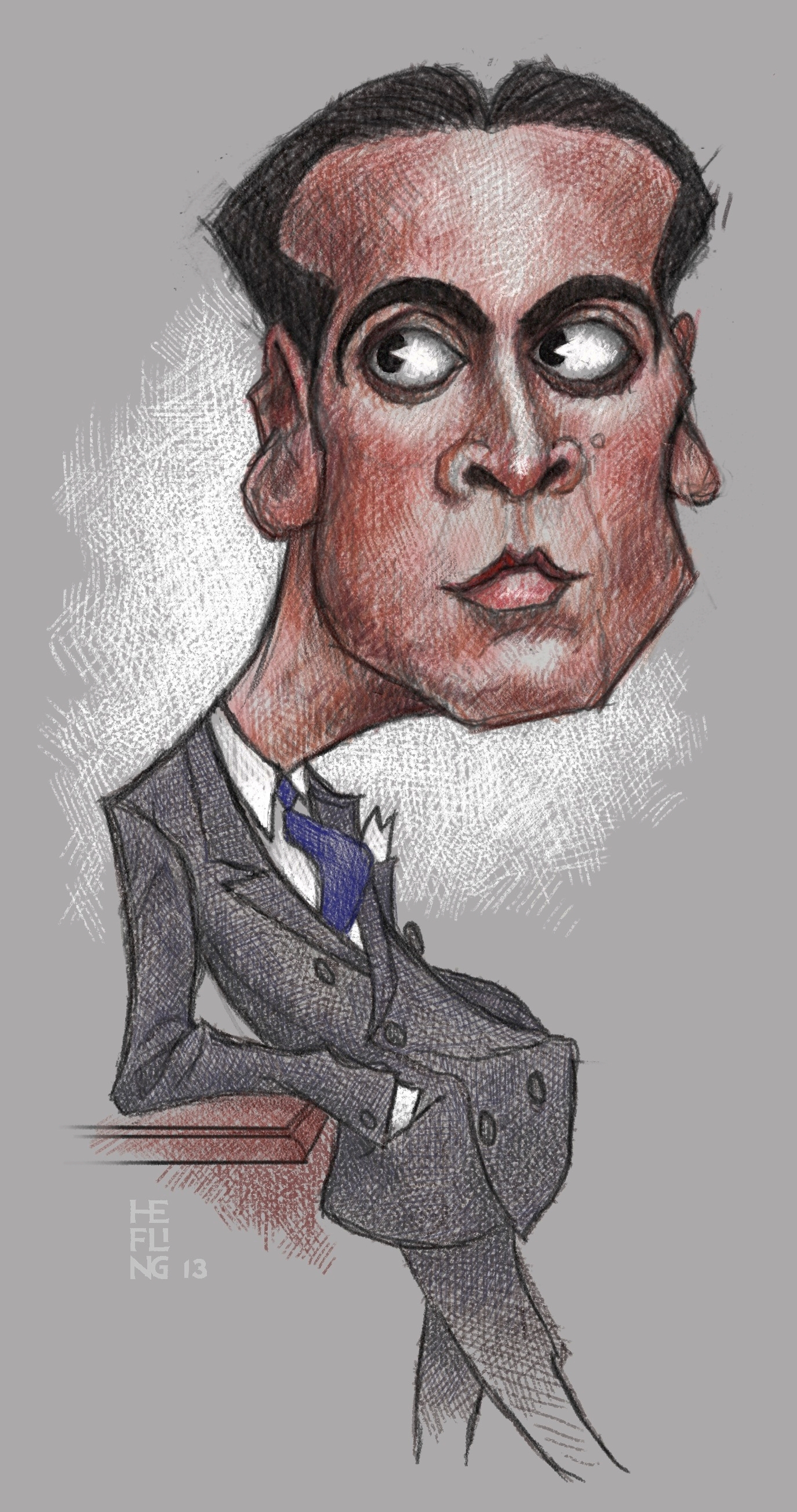

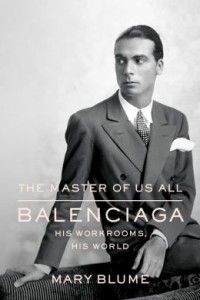

The Master of Us All: Balenciaga, His Work,

The Master of Us All: Balenciaga, His Work,

His Rooms, His World

by Mary Blume

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

240 pages, $25.

WHILE ostensibly telling the story of the great fashion designer Cristóbal Balenciaga, Mary Blume offers a wider view of the French fashion scene and larger social significance—wider, perhaps, than some might think it deserves. She relates how France’s ascendancy to haute couture “began when Louis XIV’s finance minister, Jean-Batiste Colbert, informed the king that the silk weavers of Lyons were as valuable to the French economy as the gold mines of Peru were to Spain. … Having shown that it had a use, fashion came to have a meaning. It spoke volumes to Balzac and Baudelaire and Proust.” Cristóbal Balenciaga was at the forefront of a long line of 20th-century gay designers who dressed famous women, a roster that includes Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio Armani, Calvin Klein, Gianni Versace, and Alexander McQueen (whose retrospective Savage Beauty recently closed at the Metropolitan Museum). Blume traces the elusive Balenciaga’s career from his Basque roots and Franco’s Spain to Paris in 1937, through the German Occupation and the swinging sixties to his death in 1972. The unique quality of a Balenciaga show attracted the likes of Hubert de Givenchy and Diana Vreeland, which so overwhelmed her that now “it was possible to blow up and die.” (His “sack dress” was famously parodied in an episode of I Love Lucy.) Of humble origins, Cristóbal learned dress-making at the feet of his seamstress mother, where he would play with scraps of fabric to make clothes for his pets and accompany her to fittings at the homes of her aristocratic clients. Legend has it (and there are quite a few legends about his career) that when he was twelve years old he began apprentice work, and that eventually he went into business for himself in Madrid and Barcelona. By the age of 21 he is said to have dressed the queen of Spain. The atmosphere of the divine decadence of the post-war period is mind-boggling. In 1951, Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton commissioned Mr. B. to dress her as Mozart for a Venetian ball at a cost of $15,000. (Yves Saint Laurent’s annual salary as chief designer at Dior was $14,000.) Blume reports that after a falling out with the formidable Coco Chanel, she gave an interview with Women’s Wear Daily “in which she said nothing but horrors about Balenciaga, about his homosexuality, how he knew nothing about women’s bodies, which was why he dressed them as he did.” Reportedly brought to tears by this remark, Balenciaga returned to Spain “for a fairly long time.” However, he did manage to have a twenty-plus-year relationship with the Polish-French designer Wladzio Jaworowski d’Attainville, “a well-connected young man with sleek dark hair” who joined Balenciaga at the Spanish company, where he “designed witty hats, and smoothly made contacts that Balenciaga, less experienced, was still awkward about.” One of the few unprofessional photographs of Balenciaga includes a smiling d’Attainville holding a Siamese cat. When his lover-helpmate died suddenly in 1948, in Spain, at age 49, Balenciaga was so grief-stricken that he considered entering a monastery. Legend has it that what changed his mind was seeing a client in a poorly executed Balenciaga dress. Blume fills out this biography with juicy anecdotes about Paris during the German Occupation. Cristóbal Balenciaga, a native of neutral Spain, was hardly affected by the Vichy regime and continued to design for his wealthy clients, including many Parisians, such as Chanel (who took a German lover and lived lavishly at the Ritz). Others “resisted” by “speaking French with an English accent when chatting with German officers.” The German Gestapo, aided by Vichy militias, became increasingly opressive and vicious when it appeared that they were on the wrong side of history, resorting to torture—for example, 93, rue Lauriston was a torture chamber—and strictly enforced curfews. When the Duchesse d’Ayen, from French Vogue, went to that address to find her kidnapped husband, she was placed in solitary confinement in Fresnes prison “wearing the beige jersey Balenciaga dress she was arrrested in.” The 1950s brought a “sense of renewal and youth” to Paris. “Fresh blood was welcomed and enriched by the fact that prewar old blood was still around,” Blume observes. “In the space of one spring afternoon in 1951, the ambitous and beautiful young American composer Ned Rorem met Jacques Fath, Picasso, the costume designer Valentine Hugo, and Luis Buñuel,” as well as Jean Cocteau and Francis Poulenc. “Later, with his patroness, Marie Laure de Noailles, he attended a Balenciaga collection where she noted approvingly one particularly fragile gown: ‘I can see myself drunk in that one.’” Michael Ehrhardt, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a freelance writer based in New York City.

However, Balenciaga the man is still something of an enigma. Considered the greatest couturier of his time—in the words of Christian Dior, “the master of us all”—he never actually met many of his most dedicated clients, notably Marlene Dietrich, the Duchess of Windsor, and Begum Aga Khan. One somehow suspects that Balenciaga’s low profile was due in part to his need to keep his homosexuality from public scrutiny, as well as a shrewd sense of building a unique, above-it-all mystique. He would approach clients with an air of scorn, and they would come back for more. (He watched his showings from behind a curtain peephole.) “Balenciaga never made a faux pas,” Blume explains, “because he never made a pas at all.”