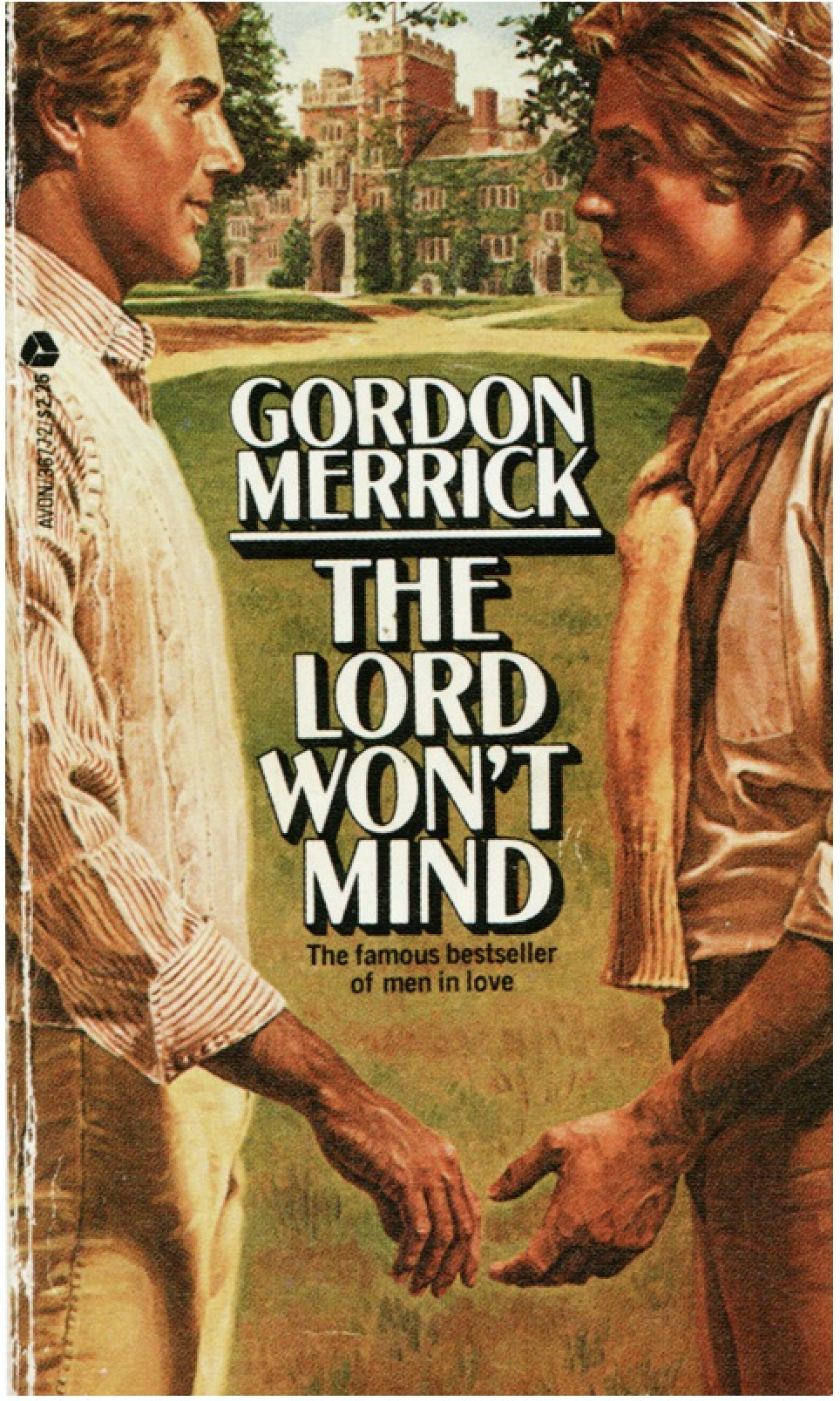

FIFTY YEARS AGO, Gordon Merrick’s The Lord Won’t Mind hit the bookstore shelves. The novel, Merrick’s fifth, set forth the romantic relationship between Charlie Mills, a dashing Ivy-educated actor, and Peter Martin, a sensitive beauty destined for West Point. Although it was published in hardcover with an innocuous cover, the novel was boldly advertised in The New York Times as “the first homosexual novel with a happy ending.”

The novel was an immediate bestseller, quickly breaking into the Times top ten list, where it remained for a stunning sixteen weeks. It was translated into several languages, including Japanese, and was regularly listed in gay book catalogues alongside works by Mary Renault and Gore Vidal. Merrick capitalized on the novel’s success by writing two sequels, One for the Gods and Forth into Light. All three novels were periodically reissued, mostly in paperback editions, and Merrick’s publishers received a steady stream of fan mail throughout the 1970s and ’80s.

But despite its popularity, The Lord Won’t Mind is rarely included in histories and anthologies of gay fiction. When it is mentioned, it’s often treated as a guilty pleasure or as an embarrassment. Historians typically classify the novel as a throwback to trashy gay romance pulps or as an unfortunate product of post-Stonewall liberation. Literary criticism has been brutal. The book reviewer for the Times minced no words when he wrote that the novel “may set homosexuality back at least twenty years.”

Critics get two things wrong about The Lord Won’t Mind. First, Merrick was not influenced by Stonewall. He started writing the novel in the mid-’60s, and his agent was already shopping the manuscript to publishers in 1968. If anything, Merrick was looking backward, not forward, when he wrote the novel. His literary models were Gertrude Stein and E. M. Forster, whose semi-autobiographical works had touched on gay themes. In fact Merrick had been friends with Forster for many years. He later claimed that he had read the manuscript copy of Maurice and had tried to persuade Forster to publish it in his lifetime.

The second misunderstanding of Merrick’s gay fiction is more interesting. Many consider the novels to be unrealistic fantasy or soapy melodrama. Gay literary historian Roger Austen called it “pleasant escape fiction for the Gay and Gray set.” To be sure, Merrick’s characters can be gushing, and his sex scenes are nothing short of sensational. However, many scenes in these novels that initially seem melodramatic or “escapist” are actually autobiographical. My own research on Merrick over the last twenty years has revealed that all of his novels include episodes that are based on events in his own life, beginning with his time as a Princeton undergraduate in the 1930s.

The second misunderstanding of Merrick’s gay fiction is more interesting. Many consider the novels to be unrealistic fantasy or soapy melodrama. Gay literary historian Roger Austen called it “pleasant escape fiction for the Gay and Gray set.” To be sure, Merrick’s characters can be gushing, and his sex scenes are nothing short of sensational. However, many scenes in these novels that initially seem melodramatic or “escapist” are actually autobiographical. My own research on Merrick over the last twenty years has revealed that all of his novels include episodes that are based on events in his own life, beginning with his time as a Princeton undergraduate in the 1930s.

Joseph M. Ortiz teaches at the University of Texas, El Paso. He is writing a biography of Gordon Merrick.