Mr. Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense

Mr. Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense

by Jenny Uglow

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 480 pages, $45.

EDWARD LEAR, born in London in 1812, produced some of the most celebrated nonsense poems in the English language, along with striking sketches, lithographs, and landscape paintings. An admirer of Tennyson, Lear would in turn delight and influence such major modern poets as W. H. Auden, Elizabeth Bishop, and John Ashbery.

Lear applied three critical skills to his work: a highly observant eye, an ear that could capture a piano tune on a single hearing, and persistent focus. Next-to-youngest of 21 children or so, he learned botany and drawing from well-informed older sisters, and by the age of eighteen he had become known for meticulous drawings of parrots and other exotic birds, and animals in the Zoological Society’s newly opened collection. But Lear’s talents were offset by a number of challenges. Nearsighted and bespectacled, he was bullied at school. He had epilepsy and throughout his life was prone to partial seizures, which he worked hard to hide, as well as bouts of asthma and depression. In addition, at a time when sex between men was a criminal act, Lear was almost certainly gay. Given such hurdles, how did he manage to build an imaginative, connected life?

With this lively and wide-ranging biography, Jenny Uglow offers an often poignant picture of a remarkably self-aware and well-liked man. Her account of Lear’s experiences and idiosyncrasies is based on his diaries (which are at Harvard), published letters, travel journals, nonsense books, and art. She describes a man who, when times were bleak, would seek fresh opportunities for travel and the company of others—inclinations that elevated his mood as well as his income as an artist. Lacking inherited money or a university education, Lear was an industrious traveler, always on the lookout for classical, biblical, or otherwise stirring sights that might appeal to Victorian buyers. Once he’d identified promising scenes in Rome, Greece, Palestine, Jerusalem, Constantinople, India, or elsewhere, he would go off on a journey to sketch them.

Lear more or less fell into the ancillary career of writing. Seldom the “life of the party,” he was yet a sought-after guest who composed limericks on the spot for the children and grandchildren of wealthy friends, many of them his patrons. On a whim he began to publish illustrated sets of nonsense verse, and they became hot sellers. An 1861 version, for instance, went through 24 editions in his lifetime, and has never been out of print.

Lear’s limericks have attitude. As Uglow notes, they laud oddity and extol “stubborn eccentrics” who upset their neighbors, often criticizing the “disapproving ‘they’ who turn up again and again.” For example:

There was Old Man of Whitehaven,

Who danced a quadrille with a Raven;

But they said, “It’s absurd to encourage this bird!”

So they smashed that Old Man of Whitehaven.

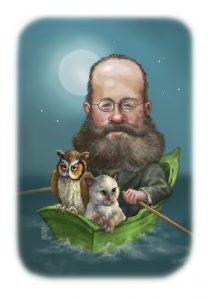

A similarly offbeat but cheerier poem, “The Owl and the Pussycat,” still polls as the top children’s poem in the UK. Lear composed it for the young daughter of his friend John Addington Symonds, a literary critic who had a wife but was also an unabashed champion of gay love. The poem celebrates an unlikely duo that embarks on a sailing adventure and ends up married—and wildly happy.

Lear himself “loved men, yet dreamed of marriage,” Uglow says, and felt distress at the impossibility of reconciling these yearnings. Though the author does not discuss the issue, at the time of Lear’s birth, British law prescribed the death penalty for sexual acts between men. In 1861 the punishment was reduced to ten years to life in prison, but decriminalization only came in 1967. So it is not surprising to learn that, while he was a prolific diarist and letter writer, Lear was also guarded. His diaries are “consistently evasive about his sex life,” Uglow says, and not all documents survive. For example, Lear formed a close friendship with Oxford student Arthur Stanley in the mid-1830s, but their letters are lost. Similarly, after a brief trip with the Danish painter Wilhelm Marstrand in 1840, Lear “burnt his diary, giving no reason.”

Lear himself “loved men, yet dreamed of marriage,” Uglow says, and felt distress at the impossibility of reconciling these yearnings. Though the author does not discuss the issue, at the time of Lear’s birth, British law prescribed the death penalty for sexual acts between men. In 1861 the punishment was reduced to ten years to life in prison, but decriminalization only came in 1967. So it is not surprising to learn that, while he was a prolific diarist and letter writer, Lear was also guarded. His diaries are “consistently evasive about his sex life,” Uglow says, and not all documents survive. For example, Lear formed a close friendship with Oxford student Arthur Stanley in the mid-1830s, but their letters are lost. Similarly, after a brief trip with the Danish painter Wilhelm Marstrand in 1840, Lear “burnt his diary, giving no reason.”

Lear’s most important infatuation was with Franklin Lushington, a crush that began when Lear was 36 and lasted until his death 39 years later. Most of Lear’s papers and drawings were left to Lushington, ten years younger and his executor, but their correspondence has disappeared, along with Lear’s diaries from two idyllic months the pair spent on the Ionian island of Corfu in 1849. Uglow surmises that Lear fell for Lushington’s looks (a pencil portrait is included), his large and distinguished family, and his intellect (a first in classics at Cambridge). The Corfu interlude was life changing, at least for Lear. “Nothing had happened, yet everything had happened. [He] had fallen in love with this man,” writes Uglow. In particular, the sojourn raised Lear’s hopes that he and Lushington might buy a house and live out their days together.

It was not to be. For nearly a decade the men exchanged letters, visited, and traveled together, but they “could not regain [their]intimacy,” writes Uglow, of Lear’s frustration. Lear reached a low point in the mid-1850s after realizing that he and “Frank” would never live together as a couple, an insight eventually confirmed by news that Lushington had gotten married. Even so, Lear continued to nurture ties, befriending Lushington’s wife and serving as godparent to their children. At several points he considered proposing to the daughter of a friend, only to reject the idea. “The ‘marriage’ phantasy ‘will not let me be’—yet … to envision it is to pursue a thread leading to doubt & perhaps more positive misery,” he lamented.

Uglow’s portrait of Lear is intricate and sympathetic, and her analysis of his creative achievements sharp. She is informative about English society and culture in the 19th century, as well as events that were happening abroad. If Mr. Lear is short on details of the nonsense writer’s private life, it seems only in keeping with his exquisite perception of boundaries.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer who lives in Cambridge, MA.