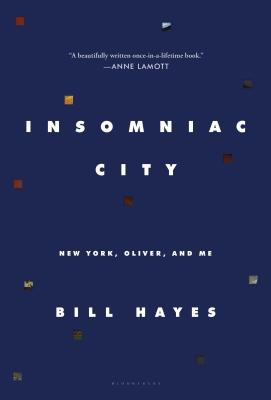

Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me

Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me

by Bill Hayes

Bloomsbury. 304 pages, $27.

AT AGE 48, brokenhearted over the death of his partner, Bill Hayes moved to New York City in order to reinvent himself. “I had simply reached a point in my life where I had to get away from San Francisco—and all the memories it held—and start fresh.” During that first fresh-start summer, Hayes began seeing a few other men. Among them was Oliver Sacks, the world-famous writer and neurologist, who had earlier written to say he had enjoyed reading Hayes’ book The Anatomist (2007). Dates with O, as Hayes refers to Sacks in this engaging, poignant memoir, were completely different. Instead of movies or new restaurants or Broadway shows, they visited the Museum of Natural History, where Sacks told him the stories behind the discovery of every single element. During long walks in the botanical garden in the Bronx, he would expatiate on every species of fern.

Hayes says that Sacks, who was 28 years his senior, was the most unusual person he had ever known.