IN 1969, a college friend handed me a copy of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949). I had no idea what the book was about, and I hesitated to accept it, since it was quite a hefty volume and I had far too much reading to do for my classes to find time to read yet another academic text. Ignoring my protests, she insisted that I must read this book in order to understand myself as a woman. Intrigued, I plunged into The Second Sex. Long story short: the book changed my life, opening my eyes to the meaning of patriarchy and its effects on all of our lives, regardless of our sex or gender.

De Beauvoir is known as a groundbreaking feminist, French Existential philosopher, novelist, memoirist, and of course as the longtime lover-companion of Jean Paul Sartre. She was born in 1908 and died in 1986 and had a younger sister named Hélène. Her family was Catholic, and her mother was a strict devotee. Her father’s thing was politics, and he was ultra-conservative. Simone was raised to be a “good Catholic girl” who obeyed the rules of the Church, the Confessional, and parental authority. She excelled as a student at the private Catholic academy for girls known as Cours Adeline Désir, located in Paris.

Much has been written about the life of de Beauvoir regarding her feminism and her sexuality. Up until 1972, she refused to call herself a feminist but then changed her mind when she learned of the revolutionary activities of what has now been termed “second wave” feminists. Also, there have been critiques made of de Beauvoir’s understanding of lesbians. In The Second Sex, she referred to theories and studies of lesbians that were prevalent in the 1940’s that focused on pathology. This critique did not contextualize her writing within the times she lived; she reported what she thought were medical and scientific findings. From today’s vantage point, these ideas are very problematical, yet they offer a window into what lesbians were up against vis-à-vis medical research and clinical practice. In any case, her feelings and ideas about feminism and sexuality were quite complex.

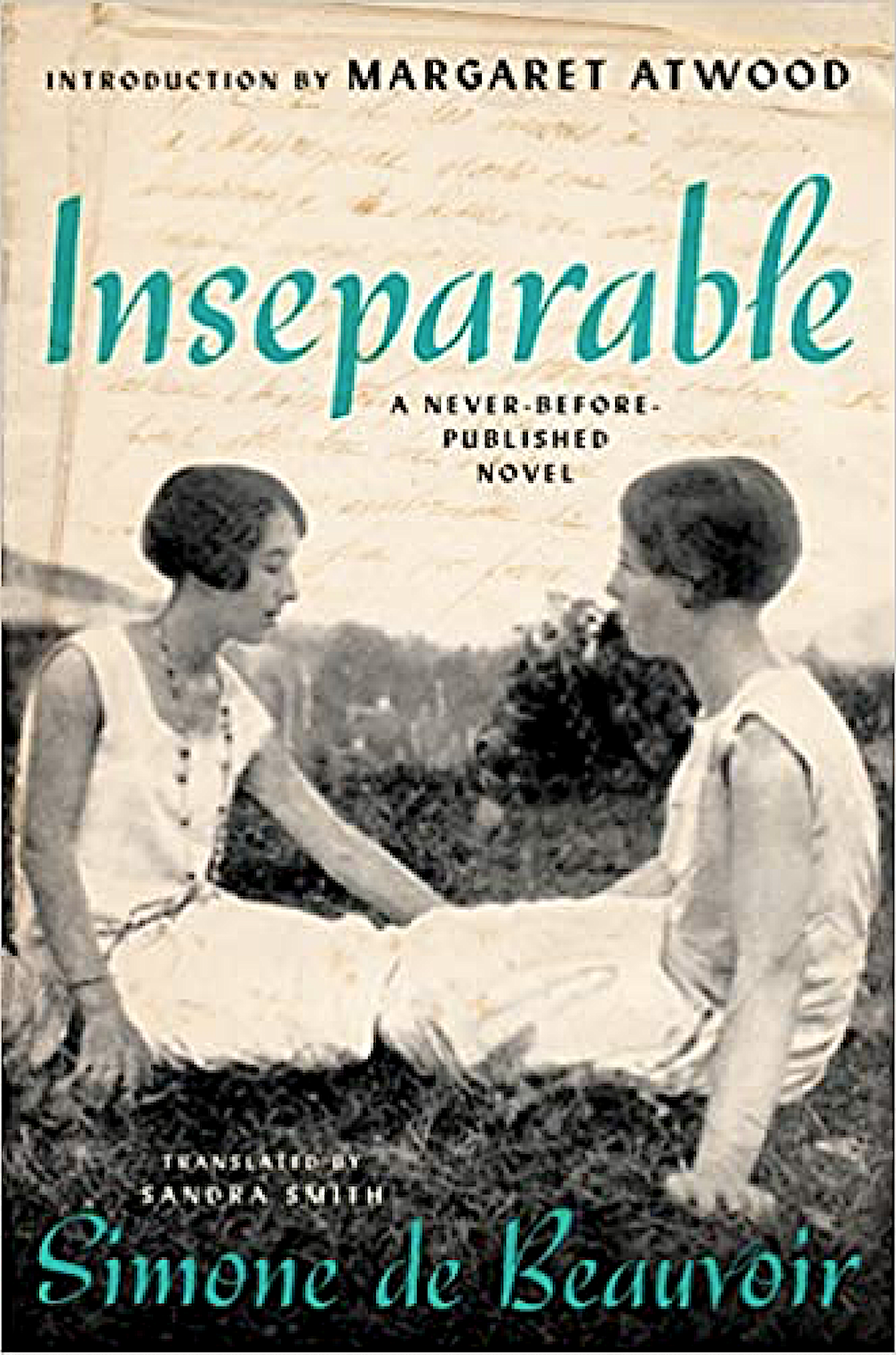

Last fall, De Beauvoir’s never-before-published 1954 autobiographical novella Inseparable came into the world. What accounted for the long wait for publication? She had shown the manuscript to Sartre, who had told her to put it away because it was “too intimate.” This assessment was presumably based on the fact that the novella dealt with the interior life of a young girl from nine years old to young adulthood, and the fact that it dealt with same-sex infatuation. It also touched upon the theme of freedom from conventional women’s rules and roles. Inseparable is a bildungsroman that documented the emotional, physical, and sexual awakenings of its protagonist. It is, in fact, a fictionalized account of de Beauvoir’s unrequited love for her friend Elisabeth Lacoin (aka “Zaza”). In the novella, Zaza is known as Andrée and Simone is called Sylvie.

Last fall, De Beauvoir’s never-before-published 1954 autobiographical novella Inseparable came into the world. What accounted for the long wait for publication? She had shown the manuscript to Sartre, who had told her to put it away because it was “too intimate.” This assessment was presumably based on the fact that the novella dealt with the interior life of a young girl from nine years old to young adulthood, and the fact that it dealt with same-sex infatuation. It also touched upon the theme of freedom from conventional women’s rules and roles. Inseparable is a bildungsroman that documented the emotional, physical, and sexual awakenings of its protagonist. It is, in fact, a fictionalized account of de Beauvoir’s unrequited love for her friend Elisabeth Lacoin (aka “Zaza”). In the novella, Zaza is known as Andrée and Simone is called Sylvie.

Sylvie’s love for Andrée is experienced as a physical longing as well as an emotional one. Sylvie has no words for her feelings but only knows that she wants to be near Andrée—to be her confidant, her companion in adventures. Unfortunately, Andrée doesn’t share these exact sentiments. She views Sylvie as her friend and not as a sweetheart. When Andrée enters puberty, she becomes increasingly less free and easy as the roles and rules for girls become more strictly defined: marriage is now the primary goal. Sylvie, however, rejects these pressures and proclaims her independence from their seemingly coercive power.

Thus Inseparable presents a world in which the stark choice is either to adapt to or rebel against society’s demands. Andrée finds it impossible to reject the pressure to conform, while Sylvie embraces the freedom to find her own road despite parental and societal pressures. Tragically, Andrée dies at the age of 21, as did Zaza in real life, just as she was about to embark on the next step in her life’s journey. Her death is experienced by Sylvie—i.e., by Simone—as a very deep loss, and she is bereft.

The fictionalized story Inseparable is detailed by de Beauvoir in her autobiography, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958), which was written four years after the unpublished novella. The memoir goes into greater detail about the importance of Zaza in Simone’s life. We learn of Simone’s idealization of Zaza’s daring brilliance and beauty when they were children, and that Simone was jealous of Zaza’s relationship with her mother because she wanted all of Zaza’s attention. Her idealized image of Zaza prevented her from perceiving that her friend was deeply troubled.

In both the novella and the memoir, de Beauvoir made the case that society’s regulations had killed off all that was unique and alive in Zaza. In both books, she suggests that she could not have embarked on her own quest for freedom had it not been for Zaza, whose death she linked to her friend’s turn to the domesticity of bourgeois life. It was the domestication of women that de Beauvoir sought to expose and deconstruct in much of her life’s work.

To the eternal question of de Beauvoir’s sexuality, I think that it would be fair to say that she was bisexual or (in today’s parlance) pansexual—prone to what Proust called “intermittences of the heart.” These were moments of change, jolts that bring one back to affairs of the past, sudden alterations of emotion, longings for past loves. She wrote in The Second Sex: “In itself, homosexuality is as limiting as heterosexuality: the ideal should be to be capable of loving a woman or a man; either, a human being, without feeling fear, restraint, or obligation.” This is how she loved Zaza.

Irene Javors is a frequent contributor to The G&LR and lives in NYC.

Discussion1 Comment

I, also, was indelibly affected by reading The Second Sex when I was 19. Having also read her memoirs and other novels, I seemed certain that de Beauvoir had been attracted to women and had sexual relationships with other women. Thank you for sharing this. I’d love to read this newly released novel.