ASSESSING the state of the LGBT print media universe is like pinning Jell-O to a wall. Whether discussing local or national publications, the situation is changing at such an accelerated pace that no one can predict the future of these media outlets. Because of the dual spears of the economic downturn and the ascent of the Internet, this inability to forecast is true of both gay and mainstream print-based companies.

In researching my new book about gay media history, Gay Press, Gay Power: The Growth of LGBT Community Newspapers in America, I focused primarily on weekly or biweekly U.S. regional newspapers, those print publications that use the traditional newsprint format. But I also summarize the history of gay media, including the rich diversity of magazines, digests, and ’zines, both local and national.

Most gay publications evolved over the course of their life-spans. Some that are weekly newspapers now, such as The Washington Blade, were once monthly or bimonthly newsletters. Some that are now national glossy magazines, such as The Advocate, were once regional newsletters or papers. Some weeklies went biweekly (Nightspots). Quite a few publications have changed their names over time. When printing and publishing technologies were more expensive, mimeograph was sometimes the only way to get the gay news out—so we wouldn’t call them “newspapers” by today’s standard, but they fulfilled that role. Of course, it’s also important to take into account what was in the pages of these publications, not just what kind of paper they were printed on.

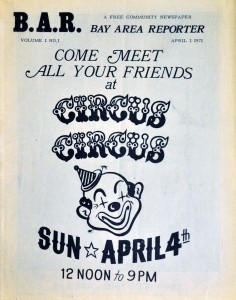

There are currently about forty weekly, biweekly, or monthly regional gay newspapers in the U.S., some of them founded more than forty years ago, some less than a decade ago. The Blade and The Bay Area Reporter, founded in 1969 and 1971 respectively, are the two oldest gay newspapers in the U.S. One factor making it difficult to predict the future is that the true state of the gay media has always been difficult to assess. Lists of the number of gay papers, compiled over the years, have varied widely in their totals and methods of counting. Often, organizational newsletters or quarterly journals were counted the same as weekly city newspapers or national glossy magazines. Sometimes lesbian-feminist papers were included, sometimes not. But based on interviews and research, it appears that the following is a likely scenario for the state of U.S. gay media since the first newsletter was published by Henry Gerber in 1920’s Chicago, Friendship and Freedom, and the first lesbian publication, Vice Versa, by Lisa Ben, came out in the 1940’s. The History of GLBT Periodicals in a Nutshell By the early-to-mid-1960’s, possibly a dozen or so additional The continued growth of the LGBT movement in the 1980’s, and the parallel devastation of AIDS, brought a new anger and energy, plus new resources, into the gay press movement. Lesbian-feminist publications continued to launch and grow, but many did not make it into the 1990’s. Meanwhile, some of the community’s strongest gay media efforts became more co-gender and flourished. There were early indications that mainstream advertisers might finally be interested in the “gay market,” but GLBT media in the 80’s were still mostly a “by us, for us” affair. Some estimates show that hundreds of gay publications operated during the decade, but the few dozen strongest were still the weekly publications in bigger cities and The Advocate, which changed from a newsprint format to a glossy magazine. By the early 1990’s, those counting were saying there were more than 1,000 LGBT periodicals of one kind or another being printed in the U.S., from newsletters to newspapers and magazines. That was the decade when corporate America truly woke up to the value of gay dollars, and as a result many more publications were launched or increased their frequencies and page counts (Out, Deneuve, Instinct, Genre, and dozens of regional titles). They added color, and glossy magazines thrived. In the first decade of the 21st century, there were signs that the gay media growth of the 1990’s was not sustainable. The national glossies started to crumble, many closed (notably Genre), and most of those that survived were sold to larger publishers or conglomerates (Out and The Advocate, which are distributed together; and Deneuve, which had been renamed Curve). The mainstream media started to cover the community more, and corporations were reaching gays through general marketing. The amount of advertising money targeting gays did not seem to keep pace with the number of media being published, and there were dozens of closures of regional and national publications. In his book The Harris Guide 2003, journalist Paul Harris (who died in January 2012) documented more than seventy national publications—he included some journals—and 160 regional publications in that year. Today, the volume of regional and national gay outlets is down to perhaps its lowest point since the mid-1970’s. Based on a 2012 review, there appear to be 103 regional and 22 national documented GLBT-related publications. This includes both newspapers and magazines, but not newsletters, professional journals, and more niche-oriented publications. So there clearly has been a drop in the overall number of print publications serving the LGBT market in the U.S. (besides the fact that some are now published less frequently). Thus, given that the gay market overall is estimated to control more than $700 billion in spending, there are actually relatively very few access points to that community through print media. The overall circulation of all these regional and national magazines is in the low millions. The quality of the publications varies widely, but it does help advertisers that one company, Rivendell Media, coordinates the placement of major national campaigns. What about the holy grail of the Internet? Won’t that save media? Even those publications with the best of websites will tell you the money still comes from print. One of the most important changes that can happen to shore up gay media is a change in attitude from companies that have LGBT customers, which is just about any consumer-based company in the U.S., from small to large. They actually spend very little of their budgets on LGBT consumer publications. The Next Generation But do we even need print media? I am in the business of print and have been producing print publications since my first family newsletter, at age ten, for 125 people. But do I need to communicate through the printed page? The answer is complicated. I know our company is strong because we have a print component that is complemented by a comprehensive website. I know the website does not carry its own weight, and if we were to go on-line only, the business would be more like a hobby. I know that the print advertisers see a more loyal and beneficial relationship with our print readers, uncluttered by the myriad marketing messages on-line. I know that for the near future, print is actually far more democratizing of information than the Internet, which is still not available to all people in the same way that free print publications are. I also know that the Internet is where the growth is, where the future is, and that those publishers who can figure out a way to combine print and on-line in a profitable formula will be the strongest ones serving their communities. Another issue of great importance is the archiving of our history. Old print editions of gay papers provide invaluable research material for historians and others looking into our past. The problem with on-line-only efforts is that, because they are often very personality-driven or done by a small team, once these folks go away, so do their archives. There have been dozens of examples of LGBT websites or blogs that simply disappear once their producers close down. Even most of those still in operation do little to create an easy way for their archives to be used, and some simply don’t save old articles or columns. Those materials are thus lost to history. Gay publications use their voices to amplify the issues and debates inside and outside our community. Now, they have to continue to make their case to advertisers who are looking for ways to amplify their own messages to the gay community. This creates an important (and sometimes awkward) symbiotic relationship between those seeing gays as consumers and the movement that needs media to investigate and cover the good and bad, the significant and the ephemeral within our communities. The challenge is not so different from the one that faced our early gay media pioneers from the 1920’s to the 50’s. Sure, the mainstream “gets us” more than ever, but it really can dedicate only a limited amount of space to our issues. Its reporters often “parachute in” to cover complex community issues, and they’re often tone-deaf to the nuances of our history and movement. GLBT media are mostly gay most of the time, and the aggregate volume of content is vastly more than the mainstream would ever bother to cover. We cover not just the next gay celebrity coming out, but the wide array of stories that actually affect the community every day. And even though the mainstream media are far more inclusive of our voices and points of view than in earlier generations, they still have a long way to go. There are many cases in which they feel the need to quote the “other side” on a topic, because society as a whole is still not fully accepting. And yet, it would be comparable to their asking the KKK for comment every time someone did a story on interracial marriage. Readers and advertisers will certainly drive the future of print and on-line journalism. But there will always be a need for independent journalism in whatever form it takes. With fewer independent voices in the increasingly corporate media landscape, we risk losing our ability to speak to one another, to be there for one another when the media forsake us, when politicians vilify us, when we are attacked with words or stones, when we want to have the depth of knowledge about our community that simply can’t be found elsewhere. But to sustain these gay media, especially in their printed form, it’s going to take innovation, a departure from past business practices, and a shift to bold new ideas. Perhaps the winning solution will be a hybrid model in which the community, advertisers, and foundations find a way to bridge the financial gaps so they can continue to cover this diverse community. Tracy Baim is co-founder and publisher of Windy City Times. This essay is excerpted and adapted from the newly published book Gay Press, Gay Power: The Growth of LGBT Community Newspapers in America, edited by Baim and published by Windy City Times and Prairie Avenue Productions). In the 1950’s, there were three main gay or lesbian publications: ONE, Mattachine Review, The Ladder. The first two were mostly for men and emerged as separate magazines after a split in the Mattachine Society in 1954, while The Ladder was published by the Daughters of Bilitis. All three were based in California. They were small-format journals associated with homophile organizations. There were also men’s physique magazines, perhaps a few dozen or more, that had a “wink-wink” understanding that their core following was among gay men.

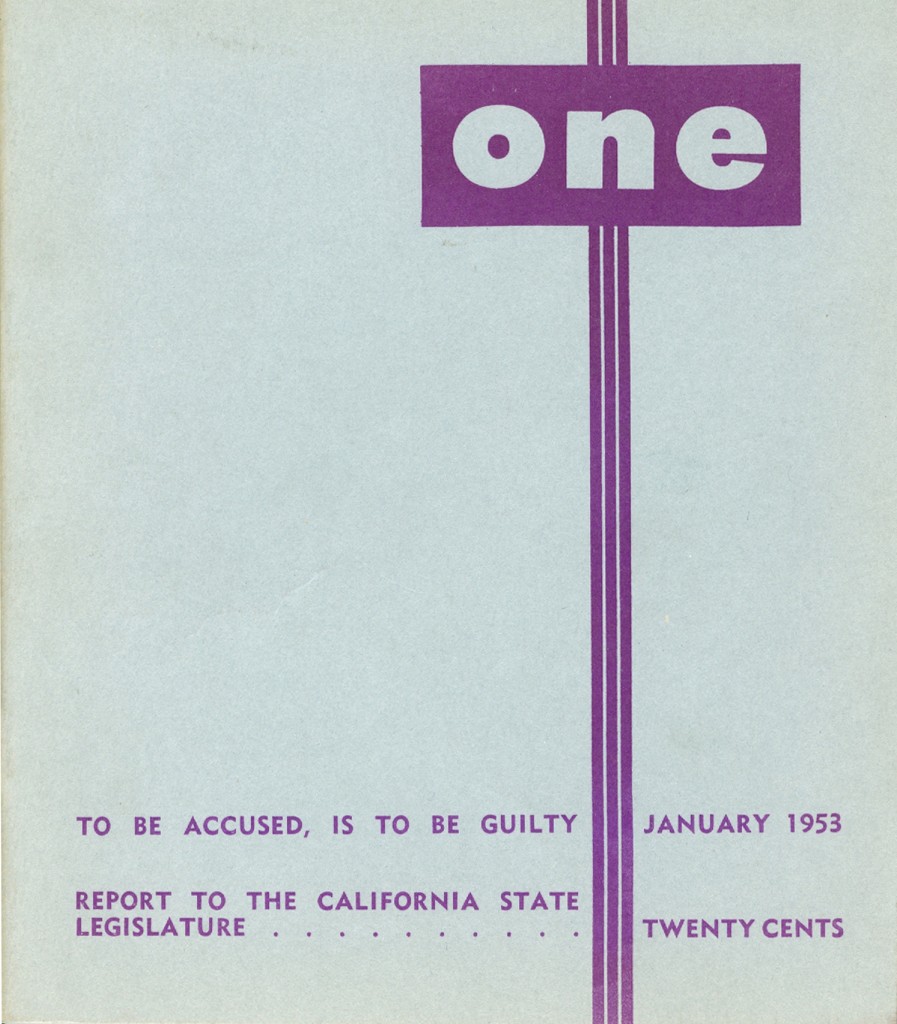

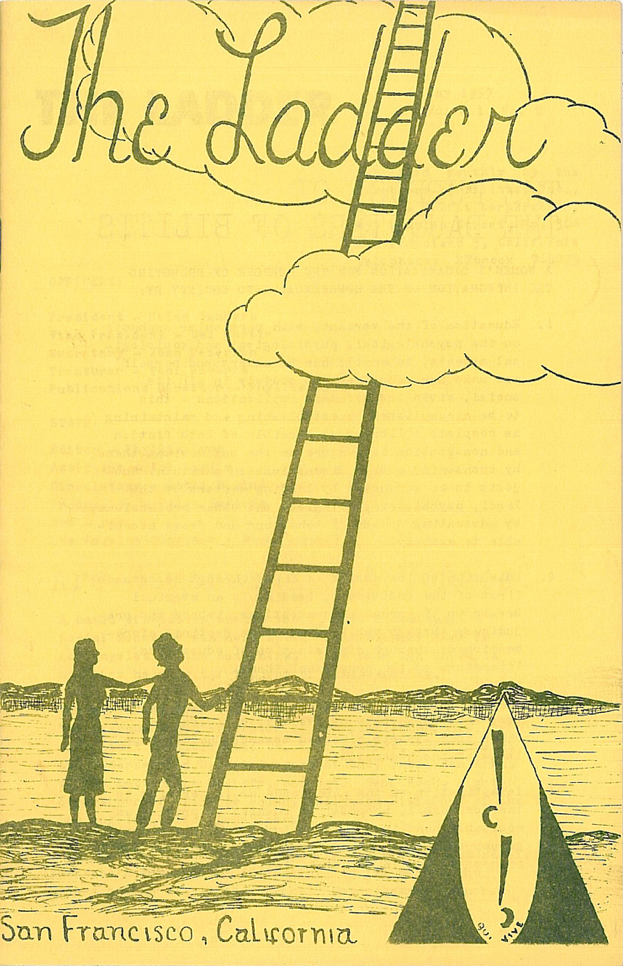

In the 1950’s, there were three main gay or lesbian publications: ONE, Mattachine Review, The Ladder. The first two were mostly for men and emerged as separate magazines after a split in the Mattachine Society in 1954, while The Ladder was published by the Daughters of Bilitis. All three were based in California. They were small-format journals associated with homophile organizations. There were also men’s physique magazines, perhaps a few dozen or more, that had a “wink-wink” understanding that their core following was among gay men. publications were launched that had a significant distribution (at least a few hundred copies) and an ongoing publishing schedule. These were primarily based in larger cities, and many were sent in the mail and passed among friends across the country. As the alternative press grew, so did the gay press, in part because of lower-cost access to printing technologies. Publications also started to become larger in format. In 1969, things were shaken up after June’s Stonewall rebellion in New York. Publications, some of them lasting just a few issues, began to proliferate. Still, there were probably fewer than two dozen ongoing gay publishing concerns with any significant distribution in that last year of the 60’s.

publications were launched that had a significant distribution (at least a few hundred copies) and an ongoing publishing schedule. These were primarily based in larger cities, and many were sent in the mail and passed among friends across the country. As the alternative press grew, so did the gay press, in part because of lower-cost access to printing technologies. Publications also started to become larger in format. In 1969, things were shaken up after June’s Stonewall rebellion in New York. Publications, some of them lasting just a few issues, began to proliferate. Still, there were probably fewer than two dozen ongoing gay publishing concerns with any significant distribution in that last year of the 60’s. In the early 1970’s, the true growth spurt began for gay, lesbian, and lesbian-feminist media. Our Own Voices: A Directory of Lesbian and Gay Periodicals, compiled in 1991 by Alan V. Miller for the Canadian Gay Archives, listed about 150 gay publications of some kind for that decade. By the 1991 publication of Our Own Voices, more than 7,200 titles from around the world were included. (These numbers are a bit tricky because it can be like comparing apples to oranges to bananas and asparagus. Our Own Voices said it adopted the broadest definition of the word “periodical.”)

In the early 1970’s, the true growth spurt began for gay, lesbian, and lesbian-feminist media. Our Own Voices: A Directory of Lesbian and Gay Periodicals, compiled in 1991 by Alan V. Miller for the Canadian Gay Archives, listed about 150 gay publications of some kind for that decade. By the 1991 publication of Our Own Voices, more than 7,200 titles from around the world were included. (These numbers are a bit tricky because it can be like comparing apples to oranges to bananas and asparagus. Our Own Voices said it adopted the broadest definition of the word “periodical.”)